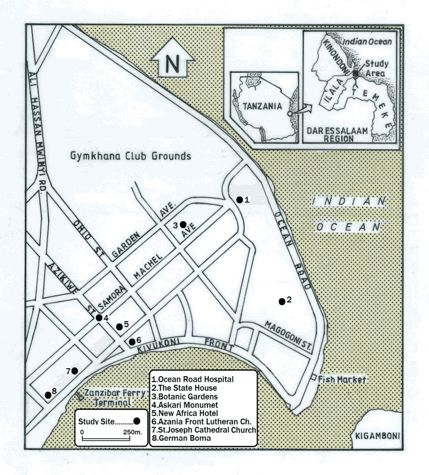

As the biggest commercial city in Tanzania today, Dar es Salaam features a number of German colonial memory sites which range from buildings, statues to open spaces. Formerly existing as a small caravan town exclusively owned by the Arab Sultan of Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam was further developed by the Germans who used it as their capital (Hauptstadt) beginning in the late 19th century. After the WWI, the city continued to serve as the capital in British mandate period until it was inherited by the independent government of Tanzania in 1961.

After independence, the city of Dar es Salaam continued to act as the capital city until it lost this administrative position to the recently established Dodoma Capital.[1] Today, the centre of the city is dotted with several colonial sites originating in German colonial period. One such site is the Askari Monument, which represents the site formerly occupied by the Wissmann Monument.

From Wissmann Monument to Askari Monument

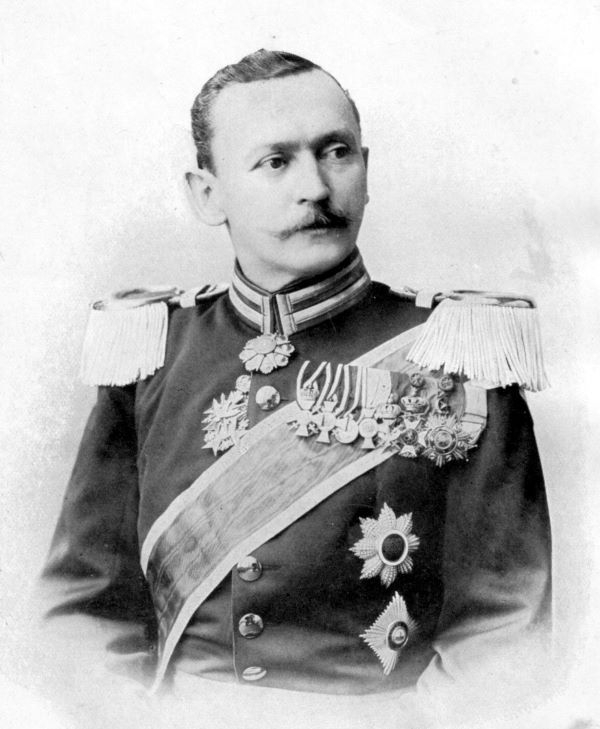

Although the British maintained the urban pattern of Dar es Salaam as it was in German times, it was necessary that some cultural images of the town were changed to suit their political ambitions. The Askari monument, a life-sized bronze structure of the King’s African Rifleman located at the junction of Samora Avenue and Maktaba Street, is traced in German times. The monument was erected in the 1920s replacing the former Wissmann Monument which was erected in 1906 in honour of Major Hauptmann Hermann von Wissmann (1853-1905), a German commander (Reichskommissar) who had succeeded in suppressing African resistances in East Africa. Coastal resistances, particularly that led by Abushiri ibn Salim al-Harthi (?-1889), a Swahili-Arab trader, posed a big challenge to Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft (OAG). For example, on 13th January 1889, the Abushiri forces set ablaze the Benedictine Mission Station of Pugu, killing three missionaries. This atmosphere of warfare called for reinforcements from Germany to “restore order and re-establish German superiority” along the coast and in the interior.[2] Wissmann was chosen for the job by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.[3] In February 1889 he left Germany for East Africa, recruited Sudanese mercenaries on his way and arrived at Bagamoyo in April. Wissmann force (Wissmanntruppe) confronted Abushiri and decisively drove him from the Indian coast to the interior, forcing him to resort to a defensive war which led to his capture and finally his execution. The result was that Dar es Salaam was rescued from the Arabs and once again restored to DOAG.

Following the suppression of the above wars of resistance by Wissmann, Dar es Salaam was, by order from Berlin, declared the capital of German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) in January 1891, replacing the former capital of Bagamoyo. Wissmann military expeditions in East Africa won him a heroic status as streets were named after him and also his monument was erected in Dar es Salaam. Wissmann Monument was a symbol of the colonial state in German East Africa which signified a “colonial self-image” and was indeed a site widely known by the inhabitants of Dar es Salaam.[4]

Although the British replaced the Wissmann Monument with the Askari Monument after World War I, the monument site continued to evoke memories of Wissmann and of German colonial history among the city’s inhabitants throughout the British period and after independence. Records show that the word, kwa-bismini, a Swahili word meaning the site of Wissmann, was still in use among the elders of Dar es Salaam as late as the 1980s.[5]

It is important at this juncture to examine why former German colonial sites such as the Wissmann Monument have continued to engender collective memories of the Germans over those of the British, who replaced them with their own. The answer lies in the fact that such sites communicated memories which were deeply ingrained in the minds of the local people. It is well known that Wissmann criss-crossed East Africa suppressing African resistance in the late 19th century, hence it is likely that he was widely remembered locally for his acts of violence. In Dar es Salaam, where his monument was erected and where the State House was constructed, memories of colonial violence endured until the post-colonial period. Minael-Hosanna O. Mdundo’s poetic work reveals that the Wissmann monument in Dar es Salaam meant that he was a colonial hero in German East Africa.[6] It must be emphasised that Wissmann was revered as a colonial hero at home and abroad by his people. In the British-controlled territory of Tanganyika his name was popularized not only by erecting his monument in Dar es Salaam but also by naming streets in different towns after him. A street in Dar es Salaam was named Wissmannstrasse, later renamed Windsor Street. Streets with Wissmann’s name existed also at other Tanzanian localities as late as the early 1920s.[7]

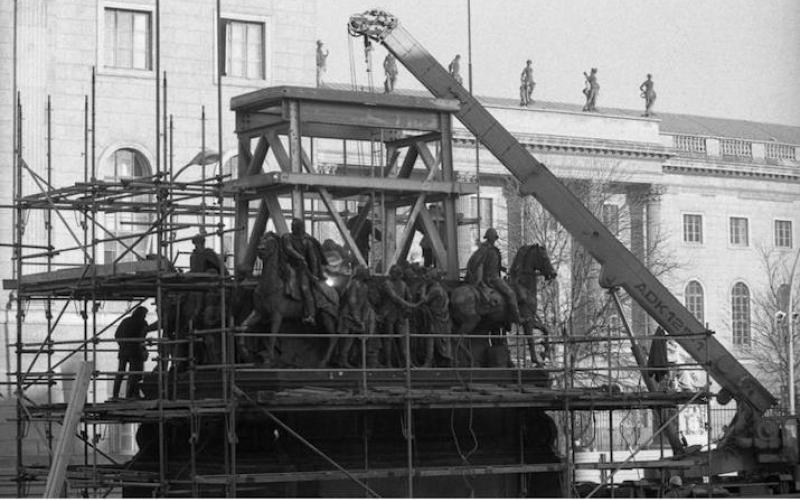

The Wissmann Monument was dismantled and put on display at the Imperial War Museum in London before the Germans, after negotiations, retrieved it in 1921 and reinstalled it in the port city of Hamburg. When the monument was toppled twice by protesting students in 1967 and 1968, it was not reinstalled. Since then, the sculpture has been shown again and again in exhibitions.[8]

From Colonial Monuments to National Monuments

By using the Antiquities Act No. 10 of 1964 and its Amendment Act No. 22 of 1979, on 8th September 1995, Tanzanian government officially recognized the city of Dar es Salaam as a historic township.[9] As a result, the Askari Monument, including several colonial buildings, was declared national monument in 2005. With this declaration, the cultural value of the Askari Monument changed fundamentally. In 1995, for example, the monument was, apart from its original function of commemorating African Askari, Carriers and Arabs who fell in WWI while serving the British Forces, described as a national monument symbolizing the culture of peace.

By and large, arguments for preservation of colonial sites in Dar es Salaam and elsewhere in Tanzania emphasize the need to decolonize colonial legacies associated with such sites. Such arguments dominated cultural heritage studies of the first three decades of independence, the time when Dar es Salaam experienced unprecedented demolition of its historic buildings, most particularly German-period buildings. Persistent demolition of historic buildings stirred public opposition and debates over the conservation of the inherited colonial sites.

Those who supported conservation argued that the value of colonial buildings transcends their historical and architectural significance as they offer “historic building resources that should continue to be used within the community.”[10] However, there was public concern over certain colonial sites whose history was thought to degrade local people.[11] The main question was, should such sites be conserved or destroyed? A consensus was reached in the 1970s when the conservation policy supported the view that such sites should be preserved for the benefit of present and future generations and for the memory of the Africans who were directly or indirectly involved in creation of such sites.

Conclusion

In most of Africa countries generally, the attainment of independence went hand in hand with demolition of colonial monuments which appeared to degrade African people. However, in places where no destruction of colonial sites took place, African governments appropriated the inherited colonial sites or monuments by redefining their roles or functions. It can be concluded therefore that deconstruction of colonial monuments in African countries has involved actions of demolition and reconstruction. Such situation reaffirms Fassil Demissie’s argument that “urban Africans are remaking and imprinting postcolonial cities with their own forms of urbanity.”[12] In particular to the Askari Monument in Dar es Salaam, Tanzanian government invented its own symbolic function of the monument as a departure from colonial interpretations of war monuments.

[1] Reginald E. Kirey, “A Long Way to Dodoma: Deconstructing Colonial Legacy by Relocating the Capital City in Tanzania Mainland”, Tanzania Zamani, Vol. XII, No. 1, 2020, pp. 44-84.

[2] Ralph A. Austen, Northwest Tanzania Under German and British Rule: Colonial Policy and Tribal Politics, 1889-1939, New Haven and London 1968, p. 22.

[3] Ifor L. Evans, The British in Tropical Africa: A Historical Outline, Cambridge 1929, p. 325.

[4] Juhani Koponen, Development for Exploitation: German Colonial Policies in Mainland Tanzania, 1884-1914, Helsinki 1994, p. 86.

[5] Lt. Minael O. Mdundo assisted by SajiniTaji Nassoro Omari, Utenziwa JWTZ (Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House, 2005), pp. 23-24.

[6] Ibid., p. 23.

[7] The Tanganyika Territory Official Gazette, Vol. I., No. 35, 14th October, 1920, p. 209; Ernest Adams, “Tanganyika Territory: Disposal of Enemy Property”, Dar es Salam Times, Vol. III, No. 7, 31st December 1921, p. 9.

[8] Gordon Uhlmann, “Das Hamburger Wissmann-Denkmal: Von der kolonialen Weihestätte zum postkolonialen Debatten-Denkmal”, in: Ulrich van der Heyden Joachim Zeller (ed.), Kolonialismus hierzulande. Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland, Erfurt 2007, pp. 281-285.

[9] Donatius M. K. Kamamba, “National Cultural Heritage Register Antiquities Division”, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Dar es Salaam, 2012, p. 7.

[10] Amin Aza Mturi, “Whose Cultural Heritage?: Conflict and Contradiction in the Conservation of Historic Structures, Towns and Rock Art in Tanzania”, in: Peter R. Schmidt and Roderick J. McIntosh, Plundering Africa’s Past, Bloomington 1996, pp. 170-190, p. 175

[11] Ibid., p. 174.

[12] Fassil Demissie, “Imperial Legacies and Postcolonial Predicaments: An introduction”, in: Fassil Damissie (ed.), Postcolonial African Cities: Imperial Legacies and Post-colonial Predicaments, London 2007, pp.2-10.

Zitation

Reginald E. Kirey, Decolonizing German Colonial Sites in Dar es Salaam. The Case of Hermann von Wissmann and the Askari Monument , in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/geschichtskultur/decolonizing-german-colonial-sites-dar-es-salaam