This essay is based on a talk I delivered at the University of Chicago in February 2024, at the invitation of Ken Moss and Na'ama Rokem. Naturally, the events of the past few months have compelled me to revise the text, especially the conclusion. The references in this essay primarily link to newspaper reports, most of which are in Hebrew. More thorough academic studies on this period have yet to be written.

1. Abandoned by the State

Despite the comparatively sparse patches of green and the ever-present swirl of dust, the road to Sderot in October 2023 felt like a journey into the desolate Zone from Tarkovsky’s 1979 Stalker. The landscape, barren and forsaken, was littered with the ghostly remains of military vehicles, strewn along the deserted highways like relics of some ancient, forgotten battle. As in Tarkovsky’s Zone, the soundscape in Sderot was unnervingly wrong. The sirens, meant to warn of incoming rockets, lay silent. Instead, the town was punctuated by the erratic thuds of shells landing nearby, mingled with the relentless roar of Israeli artillery firing seemingly indiscriminately toward Gaza. I was looking for an address. Google Maps and other GPS services ceased to work in Sderot, and, with no one to ask for directions, one was left at the mercy of the confusing street signs and a list of landmarks that were supposed to take us to our destination: a cul-de-sac, yellow fence, a billboard showing an ad from the recent election campaign that reads "Vote Netanyahu! Strong Against Hamas."

The town of Sderot sits in the northwestern corner of the Negev Desert, just a few kilometers from the Gaza border. In the fall of 2022, during the general elections, 78 per cent of its residents cast their vote for the current Israeli government.[1] The first people I encountered in Sderot were a few dozen volunteers gathered at a local community center. Among them stood out a few who were wearing conspicuous T-shirts emblazoned with the name of their group, "Brothers in Arms" (Achim La'Neshek), an organization of Israeli veterans that had been at the forefront of the fierce protests against Netanyahu's government and its attempt to change the fundamentals of Israel's democracy.[2] In the immediate aftermath of Hamas' attack, Brothers in Arms launched a volunteer operation to rescue citizens trapped near the Gaza border, an area still crawling with Hamas militants.[3] The operation reflected what many Israelis envision as the best version of their country: eager volunteers teaming up with strangers to risk their lives for others; retired military officers briefing them with sharp efficiency and a touch of dark humor; and within no time, a specially designed app—developed by the industrious minds of the "startup nation"—was in place to streamline communication between the rescuers and evacuees. Even though I was not a member of Brothers in Arms, a combination of curiosity and a restless inability to stay at home led me to join. My assigned partner was a towering six-foot biker, proudly armed—two traits I did not share. We were given an address and tasked with escorting a family from Sderot to the headquarter. When we finally located them I encountered something I had never seen before: pure, raw, existential fear. The father, a man in his fifties, and his daughter bolted from their building toward the parking lot the moment they saw us. Dazed, broken, they jumped into their car and sped off so quickly that we could barely keep up.

I saw the same fear and helplessness elsewhere, a few days later, in Ein a-Rashash. This small West Bank community of Palestinian shepherds, who relied on a modest spring to provide water for their villagers and goats, had long been harassed by Jewish settlers. But since the war began, like in so many other communities in the region, the harassment had escalated into death threats, destruction, and looting. First, the settlers fenced off the spring—the only water source for the Bedouin villagers—and guarded it with weapons, turning it into a swimming pool exclusively for Jews. Any villager who dared approach for water was beaten. In similar cases in nearby areas, they were shot.[4] Then the settlers arrived with trucks, claiming to "pave a new road," driving the trucks right through the makeshift homes of the Bedouins. They came again, this time with guns, stealing whatever remained of value, promising to return with greater force if the shepherds did not leave. By the time I arrived during the war’s third week, as part of an initiative from the NGO "Looking the Occupation in the Eyes," which aims to raise awareness of and protect against settler violence, the Bedouins had already made the painful decision to abandon their village and seek refuge elsewhere. Some of us, outraged, helped dismantle the homes; others, less familiar with the situation, naively insisted on calling the military for protection. What we discovered was even more devastating: the illegal settler outpost driving the shepherds away was practically in the backyard of a nearby military base. The local officer made it clear he supported the settlers’ efforts to "open the road" through the village. As dusk approached, around 4 p.m., we prepared to leave. And there it was again—that look of profound helplessness and fear, etched onto the faces of those who had no choice but to flee.

In Sderot and in Ein a-Rashash, as in so many places across Israel in the chaotic months following the October 7 attack, the government and its agencies seemed to have vanished into thin air. The very institutions tasked with ensuring security, welfare, the protection of basic rights, and the rule of law had crumbled under the weight of the crisis.

2. Power

The elections in November 2022 ended in an almost tie: 2,304,964 votes for the parties that comprise Netanyahu's coalition; 2,331,788 votes went to the current opposition. Yet due to Israeli election laws, about 400,000 votes were not counted (of which 300,000 would go to the current opposition).[5] As a result of this practice, the division of parliamentary seats granted the coalition a clear majority: 64 seats against 56. On January 4th, 2023, Minister of Law Yariv Levin introduced his plan for "Judicial Reform," initially comprising four laws that eventually expanded to seven.[6] These laws were designed to severely limit the Supreme Court's ability to review or block government policies or legislation. Without a binding constitution and an independent legislative branch, the Supreme Court and government legal advisers have evolved into Israel's primary—if not sole—effective mechanisms of checks and balances. While they were anything but faultless, especially with regard to Palestinians' rights, these institutions have served as the final barrier against the overreach of governmental power, acting in the absence of the formal constitutional safeguards present in other democracies. Levin, therefore, sought to eliminate any form of criticism or limitation on government authority.

This abrupt move emerged from a sense of urgency on the part of the coalition members, and a belief that the current administration provides a unique opportunity for a fundamental change. The urgency was felt in regard to three fundamental needs. First, the need to normalize and legalize corruption. Many leading figures in the coalition, including some prominent ministers and Netanyahu himself, have been convicted or are being tried for corruption. The court has been particularly lenient in most of these cases, but it is still a source of concern, especially for Netanyahu, who is currently facing four charges of major corruption. Second, many coalition members viewed the principle of legal equality—specifically, the requirement that laws grant the same rights and duties to all citizens—as an imminent threat to their sectorial privileges. This principle has been a point of contention, particularly for Ultra-Orthodox Israelis, who wish to preserve and expand privileges such as exemption from military. Third, unlike in any previous government, the comparatively small fraction of radical West Bank settlers (some 2-5 per cent of Israeli population) can dictate government policies. The representatives of the radical settlers saw it as a rare opportunity to make irreversible changes. While the Supreme Court has generally legitimized the settlements and been lenient on Palestinian human rights infringements, it has imposed limits, particularly in cases involving the seizure of private Palestinian lands and race-based policies within Israel.[7] With a curtailed court, this fraction hopes to change this tendency and launch a much more aggressive policy against the non-Jewish dwellers in the West Bank.

The historian Jacob Talmon has famously termed the approach Levin champions as "Totalitarian Democracy," where the government claims to be the realization of the people's "genuine will," and therefore, to have the right for unlimited power,[8] Thus, early on it had become clear that the political conflict that tore Israeli society in 2023 was in fact a fight for the future of Israel's democracy.

Like various historical precedents for the shift from liberal democracy to totalitarian democracy, the Israeli government was determined to act decisively, before its opponents could effectively react to it. Simply put, like its historical counterparts, notably in 1933 Germany, Netanyahu's 2023 regime sought to swiftly reach a point of no return, where it would become impossible to stop or replace the ruling coalition, all while maintaining the pretense that they were merely implementing superficial, legitimate changes within a democratic framework. By the winter and spring of 2023, Israel was inching dangerously close to this point of no return.

Even before January 2023, Israel was steadily moving in the direction the current coalition desired, mainly due to the liberal middle class' growing indifference to social and political issues that did not directly threaten its interests. This was most evident in the general disregard of this group toward the apartheid policies being enacted in the West Bank.[9] The increasingly privatized education and healthcare provided the liberal bourgeoisie with satisfying services, leading many of this group to overlook the simultaneous degradation of public services by successive Israeli governments. The ongoing depoliticization of liberals is most visible in their tendency to vote for centrist parties.[10] As a consequence, they abandoned the political arena to sectorial powers—the settlers, the Orthodox, and the corrupt. Moreover, the Supreme Court itself had become increasingly "conservative" in the past two decades, exhibiting a growing reluctance to interfere in government policies.[11] Levin’s move, therefore, was not a defensive response to a politically powerful liberal minority or an overreaching liberal court. Rather, it was a calculated effort to rapidly alter the rules of Israeli politics, ensuring that any future attempts to limit or challenge the current coalition would be rendered impossible.

3. Protest

The widespread indifference of the middle class until January 2023 is precisely why the protest movement that emerged was both surprising and crucial. In hindsight, however, this rapid and effective mobilization did not emerge from a vacuum—it was the culmination of Israel’s long history of protest. Several key moments in that history played a critical role in shaping the current movement.

The Social Justice Protest of 2011—also directed against Netanyahu’s government—was relatively short-lived and yielded limited results, but it revealed the potential of a broad coalition of demonstrators. It was careful to present itself as “non-political,” allowing tens of thousands to join without being labeled as part of “the left.” Previous protests in Israel deemed “sectorial”—such as Wadi Salib in the 1950s (by “Moroccan” Jews), the “Black Panthers” (Mizrahi Jews), or the 2005 radical right protests against Israel's withdrawal from the Gaza strip—had little success. By contrast, the protest following the Yom Kippur War in 1974 united both left and right, leading to Prime Minister Golda Meir’s resignation. For this reason, the 2011 movement intentionally highlighted and chanted slogans such as "No Politics!" and "The People Demands Social Justice," without directly referring to the leaders who may be the source of injustice. However, 2011 also exposed the limitations of being “apolitical”: it was difficult to exert pressure on the government without aiming to replace it.

The “Black Flags” protest movement, which began in May 2020 when Netanyahu was first indicted for corruption and called for his resignation, offered several additional lessons for activists. It pioneered a new form of protest: weekly gatherings every Saturday night, not only in central urban locations like Rabin Square in Tel Aviv and outside the Prime Minister’s residence in Jerusalem, but also in front of ministers’ homes, at crossroads, and on bridges across the country. The movement maintained its strength through an intense and strategic use of social media, tailoring content for different demographics, locations, and political leanings. While rooted in local grassroots initiatives, the protests were effectively coordinated by civil society organizations such as the Movement for Quality Government in Israel, New Civil Contract, Rise Up Israel, and the anti-occupation movement Zazim, which had all been advocating for various causes before coming together to fuel this larger effort.

The 2023 protesters learned both from these movements’ successes and from their mistakes. From the beginning, it involved civil society organizations to raise money for the demonstrations, to coordinate rallies with the police, and to ensure the existence of a broad coalition. In some places, this meant an uneasy but functional co-existence between the militaristic "Brothers in Arms" organization and the radical leftist group "Looking the Occupation in the Eye." Government-supporting media outlets, such as TV Channel 14 and the tabloid Israel HaYom, quickly identified this as the Achilles' heel of the protest movement, focusing on the occasional appearance of Palestinian flags among left-wing protesters. However, the movement soon found an effective way to maintain diversity by adopting the Israeli flag as its central symbol; the tens of thousands of Israeli flags thus overshadowed any other flags or banners carried by dissenting protesters. By doing so, protesters could position themselves as the "true" patriots—regardless of the disagreements between them—standing in contrast to the government and its supporters.

Alongside the organizations already mentioned, academia played a leading role in the struggle against the "reform." Academic groups like the Law Professors' Forum for Democracy, Israel Young Academia, and the Protest of Social Workers ("OSot Mecha'a") organized educational sessions across the country. Outside of such organizations, many university professors engaged in ongoing efforts to communicate their concerns about the reform to the general public in various podcasts, public statements, interviews and essays in popular magazines.[12] At the Hebrew University, for example, professors held "Hyde Park events" on the sidelines of the protests, where they delivered impassioned speeches outlining the dangers of the proposed reforms. This intellectual engagement added weight and credibility to the movement, helping to galvanize more widespread opposition and deepen public understanding of the government's endeavor. While the government continued to assert its right and power to push the legislation forward, the protest scored several key victories that slowed its progress. By October 2023, the movement was on the brink of halting the "reform" altogether, effectively stalling the government's plans.

4. October 7

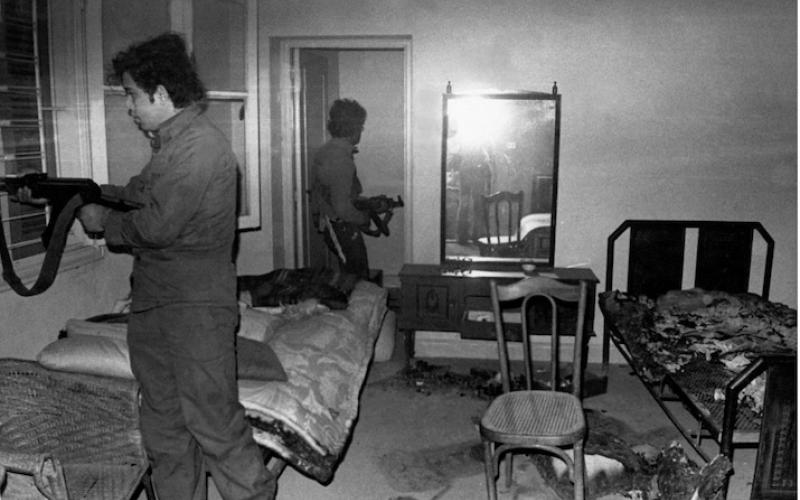

The October 7 attack sent shockwaves through Israel. It took at least two to three days before Israel regained control over its territory around the Gaza border. In the chaotic aftermath, hundreds of civilians who had survived the initial assault were still hiding in areas controlled by Hamas. With the military absent, civilians and retired generals took matters into their own hands, venturing into the dangerous territory to rescue survivors. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of civilians from towns near the Gaza and Lebanon borders sought to flee, but the government had effectively shut down. Those who managed to escape became refugees within their own country, many without a place to stay, jobs, or schools for their children. As reserve forces drafting began, it quickly became clear that the military was unprepared, relying on donations for basic supplies, from food to bulletproof vests. Across Israel, farmers found themselves without workers as foreign laborers fled and many fields lay abandoned near the borders.

Into the void rushed the civil society organizations I mentioned before. Their ability to act quickly and effectively was based on the infrastructure and experience they acquired during the anti-reform protests. By October 7, they had lists of numerous committed activists, organized into special interest groups and cells through social networking apps (WhatsApp, Slack or X), with a hierarchical mechanism for spreading messages. In 2023, they had developed effective means to raise money to fund their operations, both through a network of donors and through selling merchandise. And they learned how to mobilize people across the country to participate in rallies and sit-ins. All of these resources were quickly put in the hand of a vast army of volunteers. As a result, within days, movements such as "Brothers in Arms," "Kaplan Power," "Protectors of the Shared Home" and others transformed into disaster-response agencies, providing headquarters to assist victims, accommodate refugees, and even to provide supply to the military.

The Emergency Roadside Service (ERS), also known as the Civilian War Room, in Jerusalem is a prime example of how quickly civil society organizations stepped in to fill the gap left by the government. Run by local students and former protest activists—through the NGOs "One Heart" and "Waking Up"—this initiative aimed to provide temporary relief to Israeli refugees fleeing the war zones near Gaza and the Lebanese border. In just a few days, the ERS expanded into a sprawling operation, occupying a five-story building in downtown Jerusalem. Despite being hastily organized, it functioned with remarkable efficiency. It quickly became apparent that government supporters, particularly the Ultra-Orthodox residents of towns like Sderot and Netivot, were in greater need than others, as they lacked the internal support networks seen in secular communities like Kibbutzim.[13]

While these organizations partially masked the failures of government agencies within Israel, the situation in the occupied West Bank took a darker turn. The void left by the government was filled by paramilitary groups of radical settlers (often referred to as the "Hilltop Youth," a name that belittles their menace). Since the collapse of the Oslo Accords in the early 2000s, the military had grown increasingly indifferent to both settler lawlessness and the violation of Palestinian human rights. Under the current government, which entrusted "security" and "civil management" in the West Bank to radical settlers like Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben Gvir, the last remnants of restraint within the military were eroded, with key officials either resigning or being forced out. After the devastation of October 7, Israeli attention to Palestinian suffering dwindled even further, emboldening settler militias and leaving them with little oversight.[14] Although a few organizations that took part in the protest continued to send activists to the West Bank to protect Palestinian farmers, they struggled to engage more mainstream protest groups, which remained focused on issues within Israel (and restricted their attention almost solely to Jewish victims), leaving the situation in the West Bank to deteriorate unchecked.

5. Forfeiting the Power of Protest

Within the protest movement, there was a consensus that aiding Israelis in distress should take precedence over continuing protests during the war. It was widely accepted that mass protests would resume “after the war,” just as they had following the Yom Kippur War in 1973.[15] This noble gesture from the movement at the war’s outset was based on two key assumptions: first, that the war would be brief and those responsible for the current crisis would not remain in power much longer; and second, that their swift, effective response would validate their original argument—that a corrupt government, led by incompetent and underqualified ministers who sought to eliminate key democratic safeguards, was incapable of handling a crisis. However, by accepting the principle of silence during wartime, the protest movement effectively forfeited its ability to influence the government until Netanyahu, who controlled decisions about the war’s duration, would allow it. Furthermore, by agreeing that protesting during wartime undermined the joint national efforts, the movement inadvertently helped brand protesters as traitors.

The prolonged war had two other devastating effects on the movement. First, it caused a division within the movement in the face of the war’s challenges. Radical left-wing groups within the movement were increasingly isolated, as other factions deemed their focus on Palestinian suffering inappropriate, at best. But more crucially, while the pre-October 7 protests were unified in their opposition to Levin's "reform," the war split the movement into two opposing camps: one advocating for an immediate ceasefire and the release of hostages, the other calling for the war to continue until a decisive victory over Hamas and Hezbollah was achieved. This rift has made it impossible for the movement to regroup, even as the government renews its efforts to push the reform forward. The second challenge emerged from the protesters’ enthusiastic willingness to serve in the military during wartime. Prior to the war, several protest leaders—most notably reserve Air Force pilots—had declared they would refuse to volunteer for service in an army led by an anti-democratic government. However, as the war began, virtually none of those pilots objected to serving.[16]

In the months leading up to October 7, several leaders of the protest movement—along with many retired military generals and prominent veterans of Israel’s intelligence agencies—repeatedly warned that Netanyahu was ignoring the growing threats from Hezbollah and Hamas. Netanyahu dismissed these warnings, insisting that preserving his coalition and completing the judicial reform were essential to Israel’s security. On the eve of the attack, these misguided priorities were starkly evident in the allocation of IDF troops: a significant number of soldiers were deployed to protect settlers in the West Bank. Meanwhile, the Gaza border was left virtually unprotected.

In the weeks that followed, the government’s incompetence became painfully clear to both its opposition and its supporters. During this period, well-organized protest groups effectively became agencies of relief, providing essential goods and services, and fostering solidarity among Israelis across deep political divides. By doing so, they mitigated the sense of crisis and helped obscure the government’s helplessness, allowing Netanyahu to remain in office and even regain the support of many of his previous voters. As of early October 2024, several reform-related initiatives, many even more radical and undemocratic than those debated in the summer of 2023, are on the verge of becoming law. Israel’s civil society is far weaker today than it was at the height of the 2023 protests. In the aftermath of the war, Israeli democracy appears poised to face a full-blown attack from the proponents of "totalitarian democracy." Like me, many Israelis were profoundly impressed, and surprised, by the number of people who rose up to protest this threat in 2023, and by their endurance over many months. Yet, after the horrors of the past year, it now seems to require an excess of optimism to believe they can do it again.

[1] Results of the Elections for the 25th Knesset in 2022 (in Hebrew), 6.10.2024.

[2] Lior Ben Ami, "We Were Asleep for Many Years, Now We are Back, with a Shared Vision," ynet, 28.7.2023. In January 2024 the organization was registered as an NGO under a slightly different name, "Brothers and Sisters in Arms," to emphasize the presence of many women among the veterans it represents.

[3] Avi Isaharof, "Evacuating Civilians from the Gaza Envelope with Brother in Arms," ynet, 10.10.2023.

[4] On the escalating violence of Jewish settlers, see, for instance, report of B'tselem from August 2024.

[5] The numbers I reference here account only for parties that secured more than 1% of the vote, but less than 3.25% (which is the electoral threshold in Israeli elections). I excluded the 56,557 votes cast for "The Jewish Home" party because its leader, Ayelet Shaked, aligned with the anti-Netanyahu bloc in previous elections, casting doubt on whether she would have joined this coalition.

[6] For Levin's declaration, see Mida, 4.1.2023.

[7] "The Supreme Court, Enabler of the Occupation," B'Tselem Statement, 25.2.2020.

[8] J. L. Talmon, The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy (London: Secker and Warburg, 1952).

[9] Organizations such as Human Rights Watch have meticulously collected and reported on the policy of Apartheid in the West Bank (i.e., where separated legal system enforce separated laws for Jews and Palestinians, including numerous restrictions on Palestinians' freedom of occupation, expression, movement, etc.). Human Rights Watch, 27.4.2023. Calling the situation in the West Bank reality is not a radical or even a partisan view (as the former director of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad has stated in September 2023. Moran Azulai, “Former Head of Mossad in an Interview Abroad: Israel is Managing an Apartheid Regime,” ynet, 6.9.2023.

[10] During the 2010s and early 2020s, the vast majority of the liberal-leaning, educated middle class votes (25-30% of the general vote) went to parties that identify as "centrist" (Yesh Atid, Ha'Machane Ha'Mamlachti, Israel Beitenu, etc.). The Labor Party (Avoda) and the Liberal-Left Party (Meretz) won together 5-10% of the votes. In the elections of 2022, Meretz failed to win 3.25% of the votes, whereas Avoda won mere 4%.

[11] Minister Itamar Ben Gvir, a leader of the most radical right-wing fraction in the Israeli Parliament explained in 2019 that he sees himself as a follower of the racist Rabbi Meir Kahane, who works through the court, not against it: Attila Somfalvi, and Alexandra Lokesh “Today, instead of going to demonstrations, I solve problems by appealing to the Supreme Court,” ynet, 21.2.19.

[12] See my humble contributions to this effort, e.g. an interview in the magazine of Haaretz were minor in comparison with some of my Hebrew University colleagues. Ayelet Shani in an interview with Ofer Ashkenazi, (’We’re Shocked by Stasi Spying on Civilians, but Israel Invades People’s Privacy Too,” Ha’aretz, 13.5.2023, or Oren Nahari interviews Ofer Ashkenazi, "A Year in an Hour - 1933", 12.2.2024, https://omny.fm/shows/a-year-in-an-hour/1933.

[13] Already by the end of October 2023, three weeks after the attack, the Israel Kibbutz Movement launched a program for the resettlement of evacuated Kibbutz communities from the Gaza area to other Kibbutz communities farther from the border. This move promised that the terrorized communities will stay together, secure, and with the means to rebuild the community. “The evacuated Western Negev kibbutzim will be able to be absorbed as whole communities in host kibbutzim until they return home,” HaTnua HaKibbutzit, 29.10.2023.

[14] As several journalists and human rights activists have noted, the success in the West Bank prompted the radical right to initiate openly racist policies also within Israel. See, for instance, David Somer and Itay Ron, "The Wildest Fantasies of the Hilltop Youth are Realize by Ben Gvir and Struk under the Fog of War," The Hottest Place in Hell: Fearless Journalism, 17.4.2024.

[15] The protest after Yom Kippur war, which led to Golda Meir's resignation, started in February 1974, three months after the war ended. The 1973 war lasted 18 days and the protest was initiated by the newly released reserve soldiers.

[16] At the outset of the war, more reserve soldiers reported for duty than the army had anticipated. Yaniv Kubovitch and Chen Ma’anit, “Motivated Reservists After a Month in Gaza,” Haaretz, 8.11.2023. This surge of motivation persisted for several months but began to wane as time went on.

Zitation

Ofer Ashkenazi, How Civil Society Saved Israel’s Democracy and, most likely, Destroyed it: . October 7 and the Protest Movement, in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/how-civil-society-saved-israels-democracy-and-most-likely-destroyed-it