This article analyzes the crimes committed by Hamas in Israel on October 7th through a comparison with other historical massacres. This can give us a better understanding of the events than exceptionalist frameworks that see the event either as a part of the "Palestinian liberation struggle" or as the continuation of historical Jewish suffering.

What Hamas did on October 7th was an act of war, perpetrated as a massacre with genocidal elements against soldiers and civilians alike, in combination with a strategy of hostage-taking.[1] If the strategy of genocide is to "end all communication" and leave only death as an option to the enemy, then the indiscriminate killing of Israelis showed such intent, comparable to the murder of Yazidis by ISIS in 2014. If, however, the intention of kidnappings by parties in asymmetrical conflicts is to "facilitate further communication" with more powerful actors, such as forcing them into negotiations, the taking of hostages on October 7th also followed this strategy.[2] Such actions are familiar from actors such as FARC in Columbia.[3]

However, interpretations of October 7th have often applied different framings to the events, most prominently the history of antisemitic pogroms and/or the Holocaust, and the history of violent resistance against colonial occupation. Both framings can be recognized as part of the widespread exceptionalism that characterizes interpretations of the Israel/Palestine conflict as sui generis (the ‘last settler colony’ / the ‘Jew as pariah? among the nations’) and thus incomparable to other cases.[4]

From a perspective of Jewish collective memory, connecting October 7th to the Shoah or to historical pogroms is a way to make sense of the violence, and to gather strength in the face of expected attempts to repeat such deeds.[5] But it does not add to our understanding as historians of what happened, because the historical context is too different. The October 7th massacre was a major escalation in a political conflict between a sovereign state and non-state actors, and not an attack on a defenseless minority such as a pogrom. Neither was it – primarily – the result of an ideology that scapegoats the Jews for the killing of Christ or the crisis of modern capitalism; instead, it followed a zero-sum logic in a prolonged ethnic conflict over territory.

On the other hand, scholars have legitimized the massacre as a milestone of "decolonization". Joseph Massad, a well-known historian of the modern Arab world, rejoiced at the sight of "colonists fleeing their settlements."[7] The equally renowned Lebanese scholar Gilbert Achcar's judgement was only superficially different. While Achcar criticized Hamas for its flawed strategical thinking, he praised the tactical success of Hamas and the blow to the "haughtiness" of the Israeli government. Murdered civilians do not appear in his analysis.[8] Other academics have argued that the actions of Hamas, even though clearly murderous, could not be classified as "genocidal" because they were only possible due to the unexpected weakness of the Israeli army, which "allowed" the massacre to become bigger than it should have been under the conditions of the power differential between Israel and Hamas, essentially blaming Israel for the massacre of its own citizens.[9]

A Comparative Approach towards October 7th as a Genocidal Massacre

Both exceptionalist framings cause problems. The latter one openly condones violence against Israelis and stands, in my opinion, outside of the realm of academic and humanly acceptable speech.[10] The former is clearly less dangerous but might de-historicize the violence of October 7th into a narrative of timeless antisemitism and Jewish perseverance.[11] An historical comparison offers the best way to avoid such academic dangers.[12] A comparative perspective on the October 7th massacre means to square the attack, its historical context, the attacker's political objective, and their ideological motivations with other cases of ethnic massacres in post-colonial territories. Three possible examples are the Hutu-Tutsi ethnic conflict in Burundi and Rwanda, the 1964 "Zanzibar Revolution", and the massacres of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975-1990.

One historical similarity between the Israel-Palestine conflict and the Tutsi-Hutu conflict in Rwanda and Burundi is their background: European colonial politics played a role in creating the conflict, and then failed miserably in trying to contain it. The British mandate power hastily left Palestine in 1948, which was already in a state of civil war. The Belgian colonial power left Rwanda in 1962, after years of growing Tutsi-Hutu tensions had already resulted in massacres in 1959. The separation of what formerly was Rwanda-Urundi into Rwanda and Burundi between 1959 and 1962 could be seen as a failed attempt to contain an ethnic conflict by drawing borders, analogous to the 1947 UN separation plan. As in the case of Israel-Palestine, the absence of viable territorial borders between the two ethnic groups doomed the attempt. Burundi and Rwanda witnessed ethnic massacres between the two groups for several decades, culminating in the 1994 genocide of Tutsi in Rwanda. The long buildup of an ethnic conflict, without lasting de-escalation, led to a spiral of radicalization.

The 1964 revolution of Zanzibar, one year after decolonization, overthrew the Omani-Arab sultan dynasty that had ruled the island and led to the destruction of the Arab minority in Zanzibar. Before that, Omani Arabs had been the elite in an established regime of racial dominance over the native majority. The "revolution" of 1964 was an uprising of the black African population of Zanzibar against the sultan and the Arab elite. Beginning on January 12, Zanzibaris organized themselves into groups and attacked Arabs and Indians. They murdered between four and ten thousand Arabs and several thousand Indians, which led to a mass exodus of “foreigners” from Zanzibar. The main similarity to October 7th is the attempt to reconquer a homeland from a perceived occupier by destroying the enemy ethnic group. In the eyes of perpetrators, the massacre lead to "freedom from oppression". This mirrors the justification for the October 7th massacre both by Hamas leadership and by pro-Hamas activists in the West.[13] But unlike October 7th, the Zanzibar massacre was “successful” in “cleansing” the island from "foreign oppressors". Its anniversary is still a national holiday in Zanzibar – a chilling reminder that massacres, from the perspective of its perpetrators, can "work out" just fine as long as there are no consequences, such as a foreign intervention or international sanctions.

The massacres of the Lebanese Civil War as the crucial comparative case

The best comparative case for the 7th October massacre though is that of the mass killings during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90). The idea that the Israel-Palestine conflict can be compared to the ethnic conflicts within Lebanon is not new. This argument was advanced before the beginning of the current war by various commentators, including Israeli academics (Oren Barak), Arab thinkers (Hazem Saghieh), and journalists (Matti Friedman).[14]

Similar to the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict, the Lebanese Civil War was an ethno-religious conflict in a territory in the Levant that was created by European Imperialism after World War I with the intention of creating a refuge for a minority group (Christians, Jews). Similar to the case of the 1948 Israel-Palestine War, the Lebanese Civil War homogenized areas that had been ethnically diverse by causing members of the various ethno-confessional groups to flee or be expelled into their group’s territorial strongholds.

Mass atrocities committed by militias against civilian populations were decisive events in this process of segregation. Among the most notorious are the Karantina massacre (~1000 victims) in 1976 against Muslims by Christian Maronite militiamen, the Damour massacre perpetrated by Palestinian militiamen against Maronites a few days later (~300 victims), and the massacre of Palestinians in Sabra and Shatila in 1982 (~1500 victims), perpetrated by Christian Maronite militias. On a mere quantitative level, those examples are similar to October 7th.

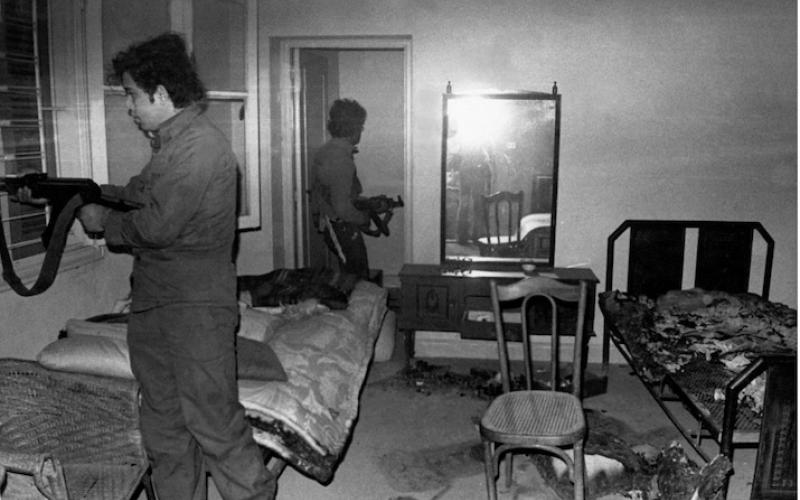

The Palestinian attack on Damour in January 1976 followed a similar course as October 7th: After breaking through the enemy lines, militiamen from the PLO and al-Sa'iqah stormed houses and massacred civilians, not discriminating between the few Christian militiamen present in the village, civilians, the elderly and children. The attackers committed acts of sexual violence and later destroyed the Christian cemetery of the village. Stories of survivors read like those of October 7th – playing dead, watching their relatives get shot to death, fearing abduction.[15] Remaining inhabitants were expelled from the village, which was later – in a desolate state – used to house Palestinians who had been expelled in a different bloody battle of the Lebanese Civil War.[16]

The massacre of Sabra and Shatila took place in September in 1982, after the Israeli invasion of Beirut. Supported by the Israeli Army, units of Phalangist (Christian Maronite) militiamen entered the Palestinian Refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, where almost no PLO fighters remained. During two days, they systematically murdered between 1300 and 3000 people, including many women and children.[17] As in other massacres mentioned in this article, rape and looting accompanied the killing. Theodor Hanf described the attack as the most brutal of all massacres in the war because it was not part of any fighting operation but "cold-blooded murder" that "lacked even the most superficial rational justification".[18] However, there was a clear rationale: leave the country, or be dead. The Phalangists wanted the Palestinian "intruders" (that is, the Palestinian who had fled mandatory Palestine during the Nakba) – who, in their view, had brought nothing but trouble – to be gone.

In a 1981 interview, the head of the Christian Phalangists, Bachir Gemayel (assassinated in 1982), stated: "There is only one people too many: The Palestinian.".[19] After the massacre, an Israeli officer quoted a Phalangist militiaman: "pregnant woman will give birth to terrorists".[20] Terrorizing the enemy until he leaves was, according to sources from Gaza, the political endgame of Hamas on October 7th: the creation of a situation where Israeli Jews ("settlers") feel the insecurity of their situation and begin to leave.[21] This ideology includes rulings from Islamist legal theory that encourage the targeting of Israeli civilians.[22] Leaders of Palestinian militant movements have justified direct attacks on civilians with the argument that they need to terrorize the Israelis enough so no Jews will migrate to Israel and the current inhabitants might leave.[23] This follows the widespread belief that Israel is an artificial state, bound to disappear if the resistance to its existence is strong enough.[24]

In both cases (October 7th, Lebanese Civil War) the perpetrating side saw their deed as an act of warfare for their own survival, and therefore made no distinction between combatants and civilians.[25] In their view, Israeli Jews are not civilians but enemy "settlers".[26] In the case of Lebanese Christian militias, it was the idea of the "terrorist" taken from Israeli military parlance.[27]

Of course, the comparison also has its limits. Each of the aforementioned comparative cases has its own unique features, and Israel is not an ethnic militia in a civil war, but a functioning state. Similarly, Gaza was a statelet before October 2023 and not merely a territory ruled by a militia.

But by comparing October 7th to other historical events, it is possible to show that the events were probably not exceptionally different from other cases of ethnic massacres: Neither more "liberatory" nor a more radical "rupture of civilization". But while it is only natural that the victims of a massacre try to understand It through the lens of their collective memory, it is unacceptable to glorify modern massacres as a path to political redemption.

[1] Israel Charny speaks of "[v]iolent acts genocidal in intent but too small to be considered genocide". Israel Charny, „Toward a Generic Definition of Genocide“, in: Geocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions, ed. George Andreopoulos (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press, 1994), 64–94. P. 77.

[2] Abdelwahab El-Affendi, „The Futility of Genocide Studies After Gaza“, in: Journal of Genocide Research, 26(3) 1–7, here p. 2.

[3] David J Topel, „Hostage Negotiation in Columbia and the FARC“, Iberoamerica Global 2, Nr. 1 (2009).

[4] For Comparison: Johannes Becke, „Beyond Allozionism: Exceptionalizing and De-Exceptionalizing the Zionist Project“, Israel Studies (Bloomington, Ind.) 23 (2018): 168–93.

[5] One example: Aviva Halamish, „Some Reflections on the October 7th Catastrophe in Historical Perspective“, Israel Studies 29, Nr. 1 (2024): 89–100.

[7] Joseph Massad, „Just another battle or the Palestinian war of liberation?“, Electronic Intifada, August 10 2023.

[8] Gilbert Achcar, „Initial Comments on Hamas’s October Counter-Offensive“, Gilbert Achcar (Blog), August 10, 2023.

[9] El-Affendi, „The Futility of Genocide Studies After Gaza“, S. 2.

[10] When asked by Jewish students for a recommendation how to deal with such speech, I regularly reply they would need the police more than my academic considerations in such situations.

[11] Philip Spencer, „The Holocaust, Genocide and October 7“, in Responses to 7 October: Law and Society, ed. Rosa Freedman und David Hirsh, (Routledge, 2024), 6–13.

[12] Levon Chorbajian und George Shirinian, Hrsg., Studies in Comparative Genocide (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1999).

[13] See Oren Barak, State Expansion and Conflict: In and Between Israel/Palestine and Lebanon. Hardcover. Cambridge University Press 2017, and Matti Friedman, „Eight Thoughts on Israel’s Political Crisis“, TabletMag, December 21, 2022.

[14] Matti Friedman, „Eight Thoughts on Israel’s Political Crisis“, TabletMag, December 21, 2022.

[15] Michel Farid Gharib, Al-Dāmūr, man anta, aw maʾsāt al-Dāmūr (Beirut: Private, 2000), P. 133.

[16] R. Fisk, Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War, Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War (Oxford University Press, 2001). P. 101f.

[17] The war and disintegration of the Lebanese state did not allow a careful study of the number of victims.

[18] Theodor Hanf, Coexistence in Wartime Lebanon: Decline of a State and Rise of a Nation (London: Centre for Lebanese Studies in association with Tauris, 1993). P. 269.

[19] Amnon Kapeliouk, Sabra & Shatila, Inquiry Into a Massacre (Association of Arab-American University Graduates, 1984). P.8.

[20] Yitzhak Kahan, Commission of inquiry into the events at the refugee camps in Beirut : final report (Jerusalem, 1983). P. 17.

[21] Shlomi Eldar, „Hamas Actually Believed It Would Conquer Israel.“, Haaretz, 4. Mai 2024.

[22] Nawwaf Takruri, Al-ʿAmaliyyāt al-Istishhādiyya fī al-Mīzān al-Fiqhī (Damascus: Dar al-Fikr, 1997) S. 171.

[23] ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ʿAjrūm, „Bayn al-ʿaqāʾidī wa-al-qānūnī“, Alpheratz Magazine, February 10, 2024.

[24] Z.B. https://www.australianjewishnews.com/nasrallah-israel-will-cease-to-exist-if-war-erupts/; compare Hassan Barari, Israelism(Reading: Ithaca Press, 2012). P. 21.

[25] Interview with Khaled Mashaal, October 19, 2023.

[26] ʿAjrūm, „Bayn al-ʿaqāʾidī wa-al-qānūnī“.

[27] Kapeliouk, Sabra & Shatila, Inquiry Into a Massacre. P. 34.

Zitation

Tom Khaled Würdemann, October 7th in Comparative Perspective, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/october-7th-comparative-perspective