I.

To what should one attribute the palpable discomfort displayed by many scholars in respect of research commissioned by corporations, foundations or ministries seeking to understand their own history – whether those scholars are the direct beneficiaries of such commissions or not? While a certain kind of journalistic polemic against such research projects – the kind which lends itself to simplistic headlines such as ‘history to order’ or ‘history for sale’, and which provides correspondingly easy opportunities for simplistic posturing – is as easy to predict as it is easy to dismiss, the deeper sense of unease surrounding the functional utility of historical scholarship, if not necessarily its direct instrumentalisation, is less speedily dispelled. The reason for this, arguably, lies in the usually unacknowledged, but thoroughly raw nerve these commissions inevitably touch, one which forces to the front of our professional identity the basically ambivalent nature of historians’ relationship to power.

On the one hand, an integral part of what unites the most disparate fields of scholarly inquiry into the past into something which can meaningful be described as a discrete discipline is the centrality of the critique of power and its operations to what historians do. On a crudely empirical level this is what unites historians interested in patterns of land ownership in fourteenth century Italy with historians of the Vietnam War, or scholars of gender in early modern Russia with historians of Japanese colonialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Whether it be Marxist accounts of the dialectic of historical change rooted in the contest for economic resource, critiques of the dispersal and exercise of power through institutional frameworks derived from the German sociological tradition of historical research, or structuralist and poststructuralist critiques of the workings of culture and language – the search for power, its governing principles, forms and effects have been at the centre of what historians seek to make sense of.

On the other hand, however, historians are themselves deeply embedded in the structures of power that, in other contexts, they seek to critique. On a banal – but in this context highly relevant – level they work inside of institutions and are thus engaged in constant competition for acknowledgement, prestige and resource, both as individuals within those institutions and when working on their behalf. The complexity of this culture, and the challenge of locating the workings of power within it, lies not least in the fact that individual scholars can simultaneously be the dispensers of such prestige and resource in one context and its recipients in another. They may sit on commissions or committees which decide over the distribution of grant money in the morning, then spend the afternoon working on a grant bid for submission to another foundation – knowing that the future of their own research project, and perhaps the employment prospects of their colleagues, depend on a successful outcome. They do so knowing simultaneously that rational scholarly judgement of the inherent quality of the project under discussion by trusted, independent arbiters determines the outcomes, but also that as scholars working within the discipline these judges are similarly participants in the same wider competition for resource and prestige, invest their time and energy not least for this reason, and exercise their judgements accordingly – not, of course, directly on their own behalf, but in the knowledge that power has its networks, and that networks know how to reward. This does not mean that academic judgement is suspended, or that academic quality does not count. To suggest this would be as absurd as the journalist polemic already dismissed. It merely acknowledges that the contest for resource takes place within a wider structure of power which is governed by something more complex than the operation of disinterested reason.

The place of historians within wider cultures of power becomes still harder to locate once one moves beyond locating the obviously institutional aspects of that power to considering the place of history and its dominant epistemologies, and the diverse places in which those are expressed, asserted, valorised, used and reinforced within a culture more generally. What is the link between the expert knowledge generated within the academy – knowledge which is sometimes barely comprehensible, let alone useful, to more than a handful of other experts – and the diverse, competing and contesting representations of the past circulating through a society more widely? Not all discourses on the past are informed by academic understandings, of course: indeed, it is striking how many such discourses are completely untouched by and unconnected to modes or repositories of knowledge generated by professional academics. Yet from serving on advisory committees in museums to acting as speechwriters for politicians, from contributing articles on historical themes to the daily news media to acting as judges in competitions to design memorials, the expert knowledge of professional historians not only helps to shape how a wider array of institutions and actors communicate to a broader public, but also legitimates the rhetorical interventions of these actors in a wide variety of public debates. Insofar as these debates have a disputatious quality, or have their own implications for the distribution of resource – perhaps most obviously when issues of compensation for historic injustices are in the air – the aura of authority with which a respected scholar’s voice can endow a particular position necessarily takes on the quality of a political resource.

These very general reflections are intended less to insist on a particular understanding of where, precisely, historians and their work sit in the power cultures of modernity than to remind that a broader perspective is needed if we are to make sense of what precisely may be at stake when historians take on the high profile commissions which have gained so much attention of late. It may be countered, of course, that such remarks operate on such a level of generalisation that they lose any operable meaning and thus offer no helpful starting points for orientating oneself in the specific problem at hand – that pointing these things out is no more helpful than telling all churchgoers that they are sinners, and that the task of differentiating precisely between different levels of sin remains. This is indeed true, but, to pursue the analogy – it is just as important to jettison the ‘holier than thou’ (päpstlicher als der Papst) stance which many historians and commentators, writing from a rhetorical position of imagined scholarly purity, but animated, one suspects, by more than a little professional jealousy, have brought to bear on the problem. That there is something worth discussing is palpably clear, but the starting point has to be a degree of self-awareness and self-criticism not always as evident in the profession as it perhaps ought to be.

II.

What, then, of the commissions themselves? The first, most obvious recent manifestation of the engagement of historical commissions has been that witnessed in the corporate world. Since the mid-1980s, and especially since the 1990s, a large number of German – and increasingly also foreign – corporations have opened their archives to teams of historians financed by the corporations themselves to examine their pasts. Starting with the initial project undertaken by the Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte on the history of Daimler-Benz AG in the “Third Reich” (published in 1987) and the Volkswagen project carried out by Hans Mommsen and Manfred Grieger (published in 1996), there has been a huge wave of company-sponsored histories examining the behaviour of individual companies in almost all branches of the economy during the Nazi era.[1] As the involvement of the company-sponsored Gesellschaft für Unternehmengeschichte in some of these projects demonstrates, the dividing line between the pursuit of Traditionspflege by the companies themselves and the pursuit of independent, critically-minded historical scholarship has been less hard-and-fast than might initially be assumed; even where corporations have engaged independent commissions rather than give the Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte the task, an element of public relations and image management has been in evidence. As Klaus-Dietmar Henke noted in respect of the Dresdner Bank project in which he participated, “Die Dresdner Bank im Dritten Reich zu untersuchen wurde möglich, als ihr Vorstand erkannte, daß fortgesetzte Indifferenz gegenüber dem Verhalten des eigenen Unternehmens im Nationalsozialismus mehr geschäftlichen und moralischen Schaden als Nutzen zu stiften begann.”[2] Indeed, only the most naïve of commentators would suggest that corporations’ engagement with their difficult pasts was prompted by disinterested curiosity in a history which had now faded sufficiently to be a matter of purely scholarly concern: the wave of company-sponsored histories which has emerged in the last two decades would be simply unthinkable outside of the context provided by the compensation debate. For the businesses concerned, contemporary corporate interests remained at the centre of the process at all times.[3]

Yet it is indisputable that this wave of commissioned scholarly accounts of business behaviour in the “Third Reich” has been of a fundamentally different quality to the thoroughly uncritical Festschriften and Jubiläumshefte traditionally sponsored by German corporations. Not least as a result of such work, historians’ understanding of the economic and business history of the “Third Reich” has improved massively, at least in the detail, in the last twenty years. At the same time, much of the uncertainty displayed by German corporations during the very public debates surrounding their role in the “Third Reich” which took place in the 1990s and 2000s, demonstrated how a corporate world which had hitherto conceived of company history purely in terms of positive tradition was completely ill-equipped to deal with the ethical and political challenge that this new critical scholarship embodied. To that extent, the findings of such commissions may be said to have had an ethical impact – however hard that may be to quantify – on the corporations and their management cultures too, if only because the historical knowledge they have generated has prompted a degree of moral circumspection in some, if doubtless not all, boardrooms too.

Ultimately, the wider political and cultural context in which the work of these commissions unfolded is such that one cannot help but reach an ambivalent conclusion. On the one hand, the commissioning of such research projects represented a playing-for-time which, given the ageing profile of the survivors of forced labour whose compensation claims rested in part on the outcome of such research, betrayed what often appeared to be an ethical indifference to the implications of such delays. Moreover, the compensation debate which provided the backdrop to these commissions was but one manifestation of the monetisation of suffering, shame and guilt which has been such a central characteristic of the discussion of historical injustices in recent years. On the other hand, concerns about the hegemonising proclivities of such commissioned research – their capacity to drown out the more critical voices of non-commissioned, completely independent scholarship and argument – may, in retrospect, have been overstated, or at least have been stated with insufficient accuracy. For, despite the much greater levels of empirical precision and the gradual shifts in the terrain on which historians have been arguing, the broad battle lines between different groups of scholars working on the history of big business in the “Third Reich” have not, despite all this corporate-funded research, fundamentally changed. Moreover, as the recent exchange between Peter Hayes, Christoph Buchheim and Jonas Scherner in the Bulletin of the German Historical Institute in Washington DC demonstrates, they have lost none of their polemical force or capacity for vigorous dispute.[4]

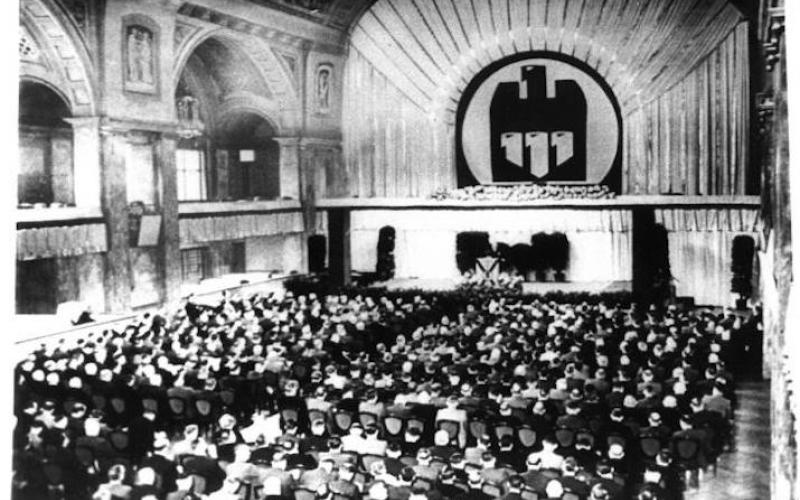

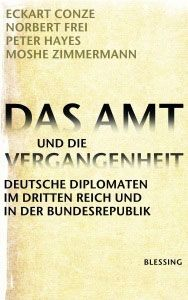

To these corporate commissions, of course, have been added a number of high profile commissions working for various Federal Ministries eager to understand their own histories in the “Third Reich”. Similar concerns to those raised in respect of corporate-sponsored histories, and a similar degree of ambivalence, were evident in the response to the findings of the historical commission on the activities of the Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt) in the “Third Reich”, which reported in the form of a co-authored study in 2010.[5] In many respects the genesis of this study and the dynamics of its reception history followed a pattern familiar from the commissioning of company histories discussed above. A dispute born in the realm of politics – in this case the controversy surrounding the publication of obituaries of former NSDAP members in the house publication of the Auswärtiges Amt – led the then Foreign Minister, Joschka Fischer, to commission an international team of leading scholars of the “Third Reich” to produce an independent report; the publication of the piece led to lively, and sometimes vitriolic criticism in which the boundaries between legitimate scholarly differences of opinion, expressions of institutionalised academic antagonism, and articulations of political sensibility masquerading as sober historical argument were not always easy to spot.[6] Again, the immediate story was accompanied by accusations of historical instrumentalisation: in this case the commission’s findings were cast as an act of ‘revenge’ on the part of progressive ‘68ers’ against the sins of their fathers, as if any such historical-political criticism could be explained in terms of the oedipal complex to which Fischer’s generation was beholden – and again, indeed, it contained possibilities for both irony and ambivalence.[7]

For all that the commission’s study may have served a particular purpose inside of the institutional politics of the Auswärtiges Amt itself, however, the most striking thing about the publication of the book and the discussion of it was, again, the extent to which both the defenders and critics of the study articulated positions long familiar to anyone with the historiography of the “Third Reich” and indeed Germany in the late 19th century and 20th century more generally. On the one hand, historians and journalists broadly associated with leftist and liberal perspectives on German politics and history argued for the deep complicity of the quintessentially conservative institution of the Auswärtiges Amt in the crimes of the “Third Reich”, and painted a picture whereby the deep reservoirs of racist, colonialist, anti-Semitic, nationalist and militarist thought which were the common sense of broad sections of the Wilhelmine economic and functional elites, provided fertile and receptive ground inside the Auswärtiges Amt in which National Socialism could take easy root and flourish. On the other, generally more conservative scholars and journalists rehearsed a critique in which German conservatism, its institutional and social anchorings and its ideological commitments were subverted from the outside and marginalised by a National Socialist movement which imposed itself largely as an alien force within the Auswärtiges Amt, pursued its destructive policies from those small and unrepresentative quarters of the office it was able fully to capture: to such scholars, the underlying precondition for Nazism’s success was not the co-option of the conservative elites but the jettisoning of their influence and the subversion of their traditional institutions.[8]

Likewise, the division between those historians – including the commission itself – who argued for the presence of significant continuities running between the “Third Reich” and the early Federal Republic, and those who were inclined to argue that any such Nazification of the Auswärtiges Amt as had taken place during the “Third Reich” was brought to a swift end by the events of 1945, by the subsequent exercises in transitional justice represented by trials and denazification, and by the swift re-establishment of democratic norms and values essentially replicated an interpretative schism which has been visible both amongst historians and the political culture of the Federal Republic more widely for decades. In this sense, much like the findings of the wave of business histories discussed above, the book has functioned simply as another intervention in a wider, pluralist discourse on the historical topic concerned, taking its chances in the court of scholarly and public opinion like any other, its arguments embodying a position broadly familiar, and indeed in many respects quite predictable, to those with general expertise in the field.[9] In this respect, at least, concerns regarding ‘history to order’ are surely prematurely alarmist.

III.

On the face of it, the long history of commissioned scholarly research into the past, which reaches back most obviously to the period following the First World War, should further assuage the fears of those who are concerned that domains of discussion which should rightly be the preserve of independent scholars are suddenly being colonised by forces seeking to re-order the public’s image of history in a manner which directly serves the interests of those in authority. It is hardly surprising, given the context, that the first former combatant state to publish its documents on the origins of the First World War was Germany: the 54 volumes of the Große Politik der Europäischen Kabinette edited by Johannes Lepsius, Albrecht Mendelsohn-Bartholdy and Friedrich Thimme aimed clearly to show, by revealing the unknown documents of secret cabinet diplomacy of the years 1870-1914, that Germany had not been to blame in the manner that the Versailles war guilt clause intended, but at worst had been equally responsible alongside all the other powers.[10] In a non-too-subtle way, this was history as propaganda, funded by the national government for overtly political purposes, and edited by patriotic historians who saw their work in terms of service to the nation. As subsequent historians, with greater access to archives, have discovered, they were often edited in an overtly partisan and distorted way, containing many sins of omission where inclusion of a document would show one’s government up in a bad way. The other countries were naturally not slow to follow: and as the emphasis placed in the official Austrian documents on the aggressive role played by Serbia in causing the outbreak of war demonstrates, the attempts to cast the origins of the war in a particular light were hardly confined to Germany. History, in other words, had become the pursuit of politics by other means. In the British case, at least, the editors concerned were well aware of the charge that they were compromising their scholarly integrity by engaging in such work on behalf of the government: directly anticipating the pained protestations of scholarly independence emanating from scholars on commissions nearly a century later, George Gooch and Harold Temperley went so far as to assert that ‘they would feel compelled to resign if any attempt were made to insist on the omission of any document which is in their view vital or essential’.[11]

A moment’s consideration of the multi-volumed collection of eyewitness testimony published on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Expellees in the 1950s as Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa – a project which similarly served directly to legitimate German claims on the lost territories east of the Oder-Neiße line – reminds further, that the recently commissioned projects stand within a nearly unbroken continuum of senior historians working on behalf of the Federal government, operating in an environment which simultaneously honoured their scholarly independence and notional objectivity and provided an obvious political context.[12] Yet in the early years of the Federal Republic no less than now, the provision of scholarly expertise to state authorities served a variety of political and ethical purposes: perhaps the most famous example of how such commissioned works sat within the broader process of the liberalisation of political culture of the Federal Republic is the affidavit on the history of the SS produced by expert historical witnesses Hans Buchheim, Martin Broszat, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Helmut Krausnick in support of the work of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial proceedings between 1963 and 1965, a key moment in the gradual emergence to wider public consciousness of the historical scale of the Holocaust.[13] And as the role played by expert witnesses such as Richard J. Evans, Christopher Browning or Peter Longerich in the David Irving libel trial of 2000 in London, historians have on occasion, and not just in Germany, been able simultaneously to serve the specific needs of their corporate hirers (in this case Penguin Books), the justice system and the wider interests of an open, democratic political culture while advancing their own authoritative scholarly judgements on the Holocaust in the process.

The point here is not to imply that the long histories of commissioned research, both in Germany and elsewhere, both for governments and for commercial interests, render the current wave of such commissions entirely unproblematic. Most obviously, both the pre- and post-war commissions on German history referred to here, reflected political contexts and served political agendas which sit uneasily with our more liberal contemporary sensibilities on nationhood, diplomacy and war; few, if any historians would admit to seeing their work in terms of service to state interests in the manner of earlier generations. In introducing – or reinforcing – his own claims on the nature of historical truth and objectivity in his expert opinion during the Irving trial, Richard Evans was also refuting the pernicious lies of Holocaust denier David Irving whilst asserting views on the nature of historical methodology which many other historians found questionable.[14] In that sense the needs of the courtroom were served rather better on that occasion than the public understanding of what professional historians think they do and what is at stake when they argue. The point, rather, in reminding of these well-known examples – which could easily be augmented with endless further ones, both in a German and non-German context, is again to suggest that either a more precise sense of what, if anything, might be different about the more recent commissions is needed if one is to advance a critique centred specifically on their work. Or, perhaps more importantly, that a slight refocusing of the critical lens is needed – one which reflects somewhat more broadly on the uses and abuses of history in civil society – if one is to draw conclusions which are both operable and genuinely meaningful.

The need for a refocusing of the critical lens is underlined further when we consider both how funding is dispensed in disciplines outside of the Humanities and how indeed many other projects are often financed in the Humanities and Social Sciences too. As far as the former is concerned, from Medicine to Engineering, Aeronautics to Climate Science, the model of applied research funded by specific, usually short-term contracts whose research agendas are defined by the particular interests – be they commercial or policy-driven – that finance the work, is far more the norm: while pure research naturally takes place in these disciplines, its pursuit is far more the privileged reserve of a minority, and those within the academy who seek to defend the space for such pure research are under constant pressure, in a world of finite resource, to put their minds to more commercially exploitable applications for their expertise. In universities dominated by physical and technical sciences, the assumption that academics will engage across interfaces not just with commercial organisations and civil authorities but also work to order for interests such as the military, and allow their research agendas to be shaped by the needs and demands of those external groups, is part of the common sense and the shared understanding of what universities are for. In Britain, where this problem is most immediately observable, the naturalisation over thirty years of an increasingly utilitarian attitude to education which sees the function of universities increasingly in terms of their capacity to act as economic drivers, combined with short-term funding constraints brought about by the still ongoing 2007/08 financial crisis which have further encouraged the acceptance of such dependencies, have led to a situation in which most university managers have abandoned a vocabulary of free scholarship and research in favour of one which actively embraces this revised sense of the function of a university in civil society. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s notorious insistence that ‘Universities should make themselves more useful’ has found its adherents both within and without the academy, across the political spectrum, for at least a generation now, with often troubling consequences.

Yet in the Humanities and Social Sciences too, it bears pointing out that the possibilities for free research have been successively curtailed over a number years as public funding bodies have sought – and successfully achieved – a privileged position in defining the terrain on which academic scholarship is pursued. Increasingly, applicants to the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) – the main British government funding body for research in the Humanities – are obliged to frame their research projects to fit with thematic priorities defined by the Council itself, in accordance with broad policy agendas determined by the government it serves. Currently, for example, it foregrounds the themes ‘Digital Transformations’, ‘Care for the Future’, ‘Science in Culture’ and ‘Translating Cultures’.[15] On the one hand, these are clearly broad enough to offer a very wide range of research options; on the other, there is clearly much of potential interest to scholars which is not easily subsumed under these headings and thus implicitly in danger of marginalisation.

As the AHRC’s description of the purpose of these makes clear, despite the very general quality of the themes it has defined, the agenda is not one of fostering blue-skies thought. To take the last one – ‘Translating Cultures’ – as an example, the Council’s webpage devoted to the subject explains firstly, that ‘we need to consider not only the complex mechanisms of translating one language into another, but also more broadly how cultural exchange and transmission functions in a variety of circumstances and periods, including communication and miscommunication, multiculturalism, toleration and migration’.[16] The direct assertion of policy relevance is impossible to miss; having touched on these political buzzwords, moreover, it continues with the explicit claim that ‘these issues have enormous policy relevance. The UK needs its policy-makers, intelligence services, legal system and police force to be fully informed about the cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity of its multi-faceted diasporic communities. We also require diplomats, charitable organisations, senior military officials and businesses who can engage sensitively with a highly complex global cultural landscape.’ For those who have still not got the point, it then underlines that ‘research in these fields informs knowledge of strategically significant parts of the world, such as Afghanistan, India, Iraq and South America, and helps us engage in true dialogue with our near neighbours in Europe in government, business and cultural matters.’ So much for pure research – scholarship in the Humanities is reduced in this way to its functional utility to government and commerce, the largely meaningless references to culture in such statements notwithstanding.

For obvious historical reasons, attempts to manage the interests of scholars in the Humanities in such an open way meet with howls of protest in Germany: for those same historical reasons, the rhetoric of academic freedom has a much greater purchase, at least on the surface. But it is worth asking whether the structures of German academe do not, in their own ways, similarly militate against the kind of free and critical thinking which critics see as being attacked specifically by the current wave of commissioned research. Looked at from a distance, the organisation of academic activities around individual Lehrstühle rather than into larger departments seems pre-destined to generate a series of highly personalised dependencies which do little to encourage the embrace of openly critical positions towards the academically senior on the part of junior scholars; this problem is compounded by the short-term and time-limited quality of contracts attached to specific career stages, which leave even academically very well-established colleagues in a professionally precarious position well into middle age. How much more free would academic expression be in Germany, one sometimes wonders, if historians were given contractual security earlier in their careers? Similarly, the proliferation of Sonderforschungsbereiche in which, across a wide variety of unrelated problem spaces, teams of researchers working on various case studies generate findings which seem, as often as not, simply to reproduce the wisdom of the initial project outline, arguably does little to sustain a culture of genuinely free research. In a banal sense, of course we enjoy ‘academic freedom’ insofar as, when confronted with a particular document in a local archive, the individual researcher is free to make whatever sense of it he or she wishes. However, the structures, institutions, processes and cultures inside of which we perforce operate, are such that what we imagine to be ‘academic freedom’ in a wider sense is in fact better described as a highly circumscribed, and therefore contained, pluralism.

IV.

These necessarily very general reflections on different aspects of the relationship between politics, finance and scholarship suggest that it would be easy to overstate the differences between the kinds of commissioned research under immediate discussion and the wide range of other research pursued both within the discipline and beyond it: these are at most small differences of degree, not fundamental differences of kind. The firm adherence to the same fundamental rules of verification as pertain across the discipline – the insistence on full access to relevant archives both for commission members themselves and, crucially, for other scholars who wish to test their findings or work on similar themes, along with the provision of full archival references in the commissions’ published findings, ensure that such works simply take their chances in the court of scholarly opinion alongside the usually voluminous other offerings in a given field. The immediate protests on the rare occasions when historians depart from those principles – witness the often derisive scorn heaped upon the literary output of the Zentrum für Angewandte Geschichte (ZAG) of the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg – reminds of the reputational risk involved in departing from the stringent standards of professional scholarship and of the swift self-marginalisation which results from ignoring the findings of the larger corpus of critical literature in a field.[17] In this sense, the mostly senior scholars involved in government or corporate commissions have rather more to lose than to gain by compromising their scholarly integrity: unsurprisingly, therefore, the answers they provide are no different to the answers they would have provided had they been financed by someone else.

If there are nonetheless grounds for concern, then, they are probably slightly different. As has on occasion been clear, scholars who have researched and written up their findings with full respect for the principles of academic independence have nonetheless delivered findings which broadly coincided with what the commissioning bodies wanted to hear. Herein lies much of the grounds for ambivalence. Most obviously, this reminds that contractual insistence on the scholarly freedom of the individual is, in itself, an inadequate defence against the charge of potential political instrumentalisation. Who, after all, appoints to the commission in the first place? Such appointments are clearly not made at random. Neither would the announcement of open competitions for such contracts, to which all historians could apply, alter the fundamental dynamic implicit in the fact that those doing the commissioning also do the appointing. But on a more fundamental level, it suggests that questions about ‘history to order’ have hitherto been wrongly formulated: if the argument is that the history has been whitewashed, the question has probably been une question mal posée. For the problem arguably lies less with the findings per se than with the research agendas that produce them in the first place. Who, after all, determines the questions we as historians ask of the past? Who should define the terrain on which we research and argue? For over a decade, the questions historians asked of the history of big business in the “Third Reich” were very palpably distorted by the interests of the corporations which financed much of the work – again, it should be emphasised, not in the sense that the academics concerned delivered white-washing accounts, but in the sense that the Fragestellungen of scholarly accounts was driven by historical questions arising from the compensation debate. Likewise, the close focus of the Auswärtiges Amt project on the role of that office in the Holocaust and on the direct continuities into the post-war era reflected a research agenda shaped by the furore over obituaries which prompted the project in the first place. It is not as if the things which interest politicians are completely different to the things that interest historians – of course there will be overlaps, which reflect the simple fact that politicians’ concerns, like everyone else’s, reflect concerns which surface elsewhere in public discourse. But there will also be differences, and those differences are crucial. Left completely to themselves, historians of the Auswärtiges Amt in the “Third Reich” would probably want to know more, for example, about the role of the office in the pursuit of wartime diplomacy or occupation policies more generally, much of which remains under-researched.

If Hans Mommsen’s remark during the debates on Das Amt und die Vergangenheit that ‘wir sind auf dem eigentlichen Wege in eine autoritäre Gesellschaft’ was, when expressed in this bald form, a little alarmist, it nonetheless correctly identified the risks to a culture of scholarly (and by extension democratic) pluralism which the channelling of often very large sums of money to a comparatively limited number of projects represents.[18] With Hans Mommsen, I would argue, indeed, that the fundamental risk lies not in the possibility of corruption on a case-by-case basis, but rather in the constantly encroaching capacity of the state, the hegemonic order or the forces of capital – call it what one will – to regulate the terrain on which scholars pursue their work. Even a moment’s comparison with the institutionalised dependencies of other disciplines on the bodies which finance their work reminds that calls for a reassertion of scholarly independence in the Humanities can all too easily appear to be grounded in conceit – the conceit of a bildungsbürgerlich conception of education rooted in the pursuit of cultural capital which is part of what constitutes and underpins precisely that culture of power to which this essay initially pointed. Retaining a strong awareness of that remains essential to the maintenance of a culture of self-critical awareness among practitioners of the historical discipline which is all too often lacking. Yet, equally, defending that independence is essential if we, as historians, are to defend our discipline’s capacity to engage in its central task – which is, again, none other than the robust critique of power itself. If the millions of euros which go into each of these large commissions were instead used to finance many dozens of doctoral projects – the themes of which were chosen by the young scholars themselves, rather than by governments, corporations, funding agencies or even the managers of large scholarly research projects - the capacity of the historical discipline to sustain that critique would surely be far better served.

Abbreviations:

ZAG Zentrum für Angewandte Geschichte

AHRC Arts and Humanities Research Council

[1] Hans Pohl/Stephanie Habeth/Beate Brüninghaus, Die Daimler-Benz AG in den Jahren 1933 bis 1945 (Stuttgart, 1987) and the subsequent study Barbara Hopmann, Mark Spoerer, Birgit Weitz, Beate Brüninghaus, Zwangsarbeit bei Daimler-Benz (Stuttgart, 1994); Hans Mommsen with Manfred Grieger, Das Volkswagenwerk und seine Arbeiter im Dritten Reich (Düsseldorf, 1996); see also (for example) Jonathan Steinberg, Die Deutsche Bank und ihre Goldtransaktionen während des Zweiten Weltkrieges (Munich, 1999); Johannes Bähr, Der Goldhandel der Dresdner Bank im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Ein Bericht des Hannah-Arendt-Instituts (Leipzig, 1999); Harold James, The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews (Cambridge, 2001); Gerald D. Feldman, Allianz and the German Insurance Business, 1933-1945 (Cambridge, 2001); Saul Friedländer, Norbert Frei, Trutz Rendtorff, Reinhard Wittmann, Bertelsmann im Dritten Reich (Gütersloh, 2002); Peter Hayes, From Cooperation to Complicity. Degussa in the Third Reich (Cambridge, 2004); Johannes Bähr, Die Dresdner Bank in der Wirtschaft des Dritten Reichs (Munich, 2006); Klaus-Dietmar Henke, Die Dresdner Bank 1933-1945. Ökonomische Rationalität, Regimenähe, Mittäterschaft (Munich, 2006); Harald Wixforth, Die Expansion der Dresdner Bank in Europa (Munich, 2006); Dieter Ziegler, Die Dresdner Bank und die Deutschen Juden (Munich, 2006).

[2] Klaus-Dietmar Henke, ‘Vorwort des Herausgebers’, in: Johannes Bähr, Dresdner Bank (op. cit.).

[3] I have offered more extensive thoughts on this in Neil Gregor, ‘Wissenschaft, Politik, Hegemonie. Zum Boom der NS-Unternehmensgeschichte’, in: Norbert Frei and Tim Schanetsky (eds), Unternehmen im Nationalsozialismus. Zur Historisierung einer Forschungskonjunktur (Göttingen, 2010), 79-94.

[4] Peter Hayes, ‘Corporate Freedom of Action in Nazi Germany’, Christoph Buchheim and Jonas Scherner, ‘Corporate Freedom of Action in Nazi Germany: A Response to Peter Hayes’, and Peter Hayes, ‘Rejoinder’, in: Bulletin of the German Historical Institute, Washington D.C. 45/2009, [zuletzt abgerufen am 23. Januar 2020].

[5] Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes, Moshe Zimmermann, Das Amt und die Vergangenheit. Deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik (Munich, 2010).

[6] For my more extensive reflections on this topic see Neil Gregor, ‘“Das Amt” und die Leitnarrative moderner deutscher Geschichte. Überlegungen zu einem Buch und dessen Rezeption’, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 62 (2011), N. 11/12, 719-731.

[7] For the term ‘a book of revenge’ (ein Buch der Rache) see ‘Macht “Das Amt” es sich zu einfach? Ein Gespräch mit dem Historiker Daniel Koerfer’, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 29 November 2010, [zuletzt abgerufen am 23. Januar 2020].

[8] The most prominent iteration of this broad line of argument was Michael Mayer, ‘Akteure, Verbrechen und Kontinuitäten. Das Auswärtige Amt im Dritten Reich – Eine Binnendifferenzierung’, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 59 (2011), N. 4, 509–532.

[9] On the quality of the debate as a ‘Schulenstreit’ see Ulrich Herbert’s comments in ‘Am Ende nur noch Opfer’, in: Die Tageszeitung, 9 December 2010.

[10] Johannes Lepsius, Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Friedrich Thimme (eds), Die große Politik der Europäischen Kabinette, 1871-1914. Sammlung der diplomatischen Akten des Auswärtigen Amtes (Berlin, 40 Vols., 1922-27).

[11] G.P. Gooch and H. Temperley (eds), British Documents on the Origins of the War (11 Vols., 1927-1938) Vol. 3, The Testing of the Entente 1904-1906 (London, 1928), viii.

[12] Mathias Beer, ‘Im Spannungsfeld von Politik und Zeitgeschichte: Das Großforschungsprojekt “Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa”’, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 46 (1998), 345-389, [zuletzt abgerufen am 23. Januar 2020].

[13] Hans Buchheim, Martin Broszat, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, Helmut Krausnick, Anatomie des SS-Staates, 2 Vols. (Olten and Freiburg, 1965).

[14] Much of the argument of Richard J. Evans, Telling Lies About Hitler. The Holocaust, History and the David Irving Trial (London, 2002) rests on distinctions – overt or implied – between ‘truth’ and ‘lies’, ‘objectivity’ and ‘bias’, the assumptions underpinning which replicate positions rehearsed in his earlier In Defence of History (London, 1997).

[15] http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/Funding-Opportunities/Research-funding/Themes/Pages/Themes.aspx (accessed 5 September 2012)

[16] http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/Funding-Opportunities/Research-funding/Themes/Translating-Cultures/Pages/Translating-Cultures.aspx (accessed 5 September 2012).

[17] Of the ZAG’s output see Gregor Schöllgen, Brose. Ein deutsches Familienunternehmen 1908-2008 (Berlin, 2008) or Gregor Schöllgen, Gustav Schickedanz. Biographie eines Revolutionärs (Berlin, 2010) or Schöllgen’s earlier Diehl. Ein Familienunternehmen in Deutschland 1902-2002 (Berlin, 2002), which emerged on behalf of the firm in the context of the controversial award by the city of Nuremberg of an honorary citizenship to Karl Diehl. On the Diehl Affair see Neil Gregor, ‘“The Illusion of Remembrance”: The Karl Diehl Affair and the Memory of National Socialism in Nuremberg, 1945-1999’, in: Journal of Modern History 75 (2003), N. 3, 590-633; on the ZAG see the penetrating critiques offered in Cornelia Rauh, ‚„Angewandte Geschichte“ als Apologetik-Agentur? Wie man an der Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Unternehmensgeschichte „kapitalisiert“‘, in: Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte 56 (2011), N. 1, 102-115 and Tim Schanetzky, ‚Die Mitläuferfabrik. Erlanger Zugänge zur „modernen Unternehmensgeschichte“‘, in: Akkumulation 31/2011, 3-10.

[18] ‘“Das ist schon ein ziemlicher Makel”. “Das Amt und die Vergangenheit” löst bei Historiker Entsetzen aus. Hans Mommsen im Gespräch mit Christoph Schmitz’, in: Deutschlandfunk/Kultur Heute, 30 November 2010, [zuletzt abgerufen am 23. Januar 2020].

Zitation

Neil Gregor, History to Order?. Commissioned Research, Contained Pluralism and the Limits of Criticism , in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/history-order