Whether they prefer revealing clothes or more modest, conservative attire, Russian women have many opportunities to display their patriotism nowadays: either by wearing T-shirts with the portrait of the president or by emphasizing their Russian Orthodox religious identity by donning traditional Sarafan dresses and festive Kokoshnik headgears, that are seen as typical elements of Russian national attire. The surge in patriotic attire is, however, not specific to women or Russia.

Embroidered Ukrainian dresses and shirts, the so called Vyshivanka, appeared at 2015 Paris Fashion Week.[1] Combat trousers and T-shirts with famous historical battles as well as folk motives on dresses and shirts featuring gods from Slavic mythology are also popular in Poland. During the pan-Turkist Kurultai assemblies the followers of Turanism wear Central Asian Chapan-overcoats, often with a modern twist, and Malakhai nomadic hats. Female South-Siberian dancers as well as Kazakh and Kirgiz pop singers are inspired by amazons and perform dressed in chain armor, helms and holding swords.

In the last decade, due to the development of the media and socio-political changes, a transnational revival of patriotic attire can be observed. This attire is on the one hand a result of the current biased re-writing of neo-national historiography within Russia, the post-Communist countries of Central Eastern Europe and Central Asia. On the other hand, this patriotic attire is conducive to the creation of a new tradition in strengthening unity within each group. Such re-invented fashion visualizes the ideology of those who wear it. A revival of patriotic attire manifests itself in various ways: neo-folk elements, traditional embroidery, festivals and the reenactment of historical scenes, religious symbols, photographs of politicians, and many more.

This article is a brief summary of my current research project, which analyzes this phenomenon of patriotic attire and its role in the re-invention of history. On the one hand, I Materialsammlung zum Thema „Wahlen in Russland“trace the performative and populist aspects of its visual manifestation, where all the sartorial elements mentioned above tightly connect to the appearance of such new cultural fusions as “Slavic Yoga”, “Turk Runes”, “Polish Zumba”, “Golden Warrior Woman”, “Hipster Perun”, “Central Asian Barbie” and “Eco Baba-Yaga”. On the other hand, I analyze the political ideology which stands behind this patriotic attire and its usage in politics.

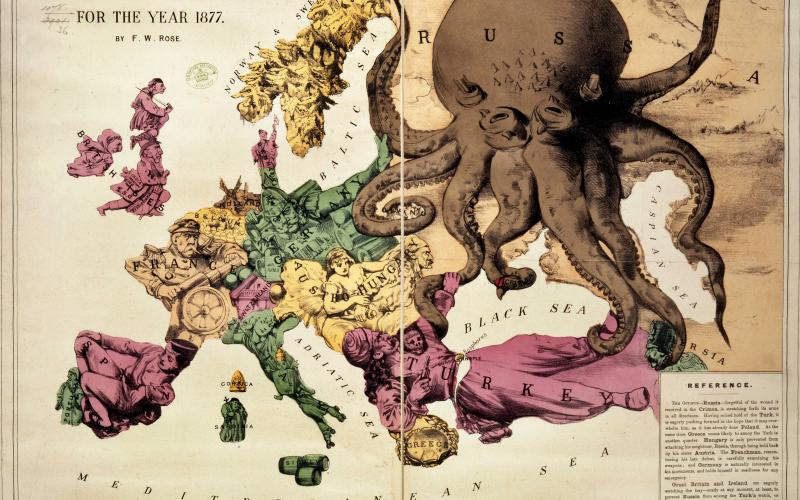

The connection between attire and nationalist movements is far from new. What is observable in today’s patriotic self-visualization is a revival of social, visual and performative patterns which had already been inherent in 19th century nationalism. Similarly, it depends on imagination and emotions: the emotional side of 19th century nationalist ideology stressed experiences of atomization of people who were seen as too detached from rural life after having moved to large cities; it emphasized the importance of their unification, in reaction to massive transformation of the social structure. The neo-nationalism in post-communist East-Central Europe and Central Asia and the rise of patriotic/folkloristic attire today were developed after the collapse of the communist regime as a part of a post-imperial/post-colonial self-reinvention process. In recent decades a new trend of self-visualization on social media significantly strengthened the performative aspect of various patriotic ideologies in these regions.

In the case of Poland, the tradition of visual group self-representation had already been strong in the early modern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, when the so-called Sarmatian costume (an orientalized Polish nobility costume) became the symbol of “Polishness”.[2]

[caption] Stanislaw Antoni Szczuka (1652 1654-1710). Wikimedia Commons. Quelle: Public Domain. [/caption]

Stanislaw Antoni Szczuka (1652 1654-1710). Wikimedia Commons. Quelle: Public Domain. [/caption]

In the time of the partitions of Poland, members of social and political movements inspired by Romanticism visualized themselves according to their beliefs. Their main emphasis was put on clothes, often inspired by the re-invented folklore attire from the southern rural areas of Galicia and the Carpathian Mountains. During the anti-Russian manifestations and uprising in 1861-1866, the so-called “Black Fashion” and “Black Jewelry” became popular among Polish female patriots as symbols of protest against the government.[3] Today’s Polish patriots continue to use the same visual messages in their attire: folk motives and symbols which had been in use in the 19th century. In addition, some of them depict motives taken from Polish history on their clothes or tattoos: famous battles or faces of political and religious leaders. Clothing also continues to be a symbol of political protest and involves imagery that makes reference to past practices – as happened during the “Black Protests” in Poland in October 2016 when hundreds of thousands of women went to the streets wearing black clothes to protest against the governmental ban of abortion.

Another example is Ukraine: In recent years, due to the political developments and the war, the embroidered blouse Vyshyvanka became a powerful symbol of Ukrainian ethnic identity, regardless of religion or language, bringing together Western and Eastern, Russian and Ukrainian speaking Ukrainians. During the last decade, an international “Vyshyvanka day” was organized, unifying Ukrainian patriots around the globe.

[caption] V. Tropinin "Lady from Podolia" (painted before 1821), Kursk gallery. Quelle: Wikimedia Commons. Lizenz: Public Domain.[/caption]

V. Tropinin "Lady from Podolia" (painted before 1821), Kursk gallery. Quelle: Wikimedia Commons. Lizenz: Public Domain.[/caption]

Vyshyvankas became also fashionable among European celebrities in the aftermath of the Ukrainian Euromaidan. The sources of the ideological usage of the Vyshyvanka, too, are to be found in 19th century Ukrainian intellectual nationalism, which had been inspired by traditional costumes. The famous Ukrainian writer and nationalist activist Ivan Franko wore a Vyshivanka under his modern European suit.[4]

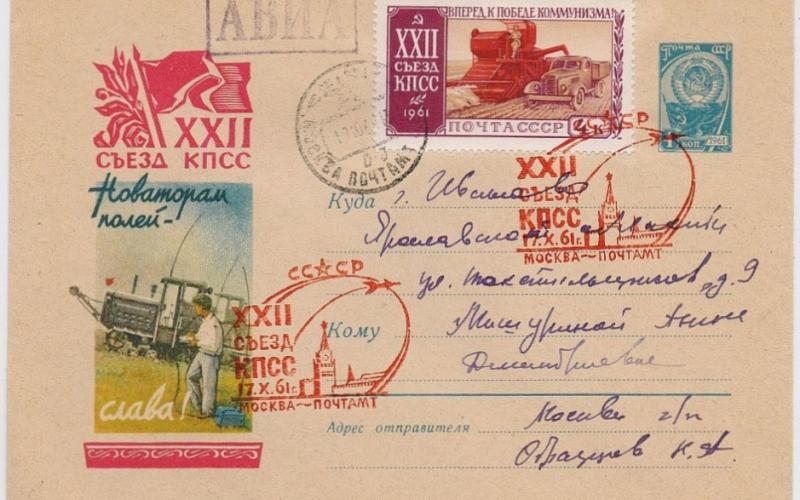

Finally, in the case of nowadays Russia, there are several directions in which the patriotic attire developed. Here I would like to mention the two most significant ones: the revival of “traditional” folk dress and portraits of the president on clothes (T-shirts and dresses). Clothes started to have a political meaning in Russia from the early modern age. During the reign of Peter the Great the traditional Russian dress was abandoned by the elite; even the appearance of lower social groups was (sometimes by force) changed to resemble European dress codes.[5] During the 19th century, dress regulations introduced by the authorities prescribed each social, professional and ethnic group to dress in accordance with its status, “unifying” its members visually, preventing diversity and creating “uniforms”.[6] During the last two decades, many Russian activists (a large part of whom are religious Orthodox) started to promote “traditional”, “Old-Russian” costumes, which real Russian patriots would love to wear.

So, The House of Russian Attire established in 2011 offers their customers “Russian” clothes, shoes and accessories, which combine folk motives with the latest Western fashion trends. This house “promotes Russian traditions in the history of fashion”.

The mission of the head designer is the “Revival of the Motherland’s greatness through the ideals of Holy Russia. Russian style in the modern world - that’s the national identity of the people”[7]. One of the latest collections named “Revival” was dedicated to the annexation of Crimea. The House of Russian Attire has close links with the Orthodox Church, therefore its clothes are connected to a certain religious and political ideology. Many discussions within the Russian Church are dedicated to the re-invention of proper attire of its female members: from shape and color to head coverings. According to the archpriest, national clothes are the garment on the icon of the Russian soul and the revival of the Russian State will start when people attend church in their national clothes. Besides the House of Russian Attire,the internet store Miryanka offers various ranges of everyday and festive clothes for religious women, who would like to be modest but still fashionable and attractive. [8]

Also Chechen Muslim designers (first of all, the spouse of the Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov herself) re-design their own attire, which is fashionable and at the same time follows the prescriptions of Quran. Moreover, Kadyrov, called “The Putin of Chechnia”, became a role model for many Chechen men who started to copy his way of semi-military dressing. Shirts a-la Kadyrov became popular among his male supporters. Another example of Muslim fashion designers in Russia is Sahera Rahmani (http://saherarahmani.ru/saxera-raxmani.html), who is of Kurdish descent, grew up in Russia and works there. Currently, Rahmani is becoming one of the most prominent designers of Islamic fashion in the region.

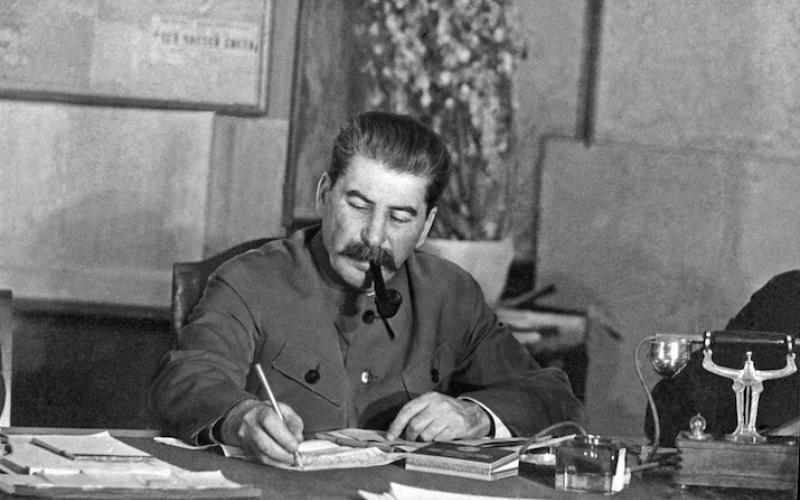

Portraits of Putin appear very often on T-shirts and are so popular that the personality of the Russian president was compared to a “Fashion brand” by one of the designers who developed the brand Putinversteher, calling to defend Russian values against Western influences. The designers of clothes with these portraits emphasize their love and loyalty to Putin, while some female patriotic activists stress their sexual appreciation of the president by locating his portrait on the breasts area. Moreover, the coming elections and the erotic admiration of the Russian president brought about an additional idea from the youth patriotic movement Set. They decided to support the president by launching a collection of shirts for women which expose cleavage through a heart cut-out that Putin holds in his hands.

According to the designer Ilya Sadalskikh “[a] portrait of the president on a T-shirt is not surprising anymore. Many young designers working in the field of patriotic fashion are looking for their own unique angle or a fresh solution. We think we have one”[9].

Portraits of Putin are used also in international relations: In October 2016, at the forum of Arab culture in Moscow, a dress made by famous Saudi-Arabian designer Mona Al Mansouri depicting the Russian president as an angel, surrounded by cherubs, holding a globe and wearing a judo kit, was presented as a symbol of unification of the Arab and Russian nations.[10]

The judo kit of the president became one of the most widespread depictions emphasizing his strength and masculinity and appears even on one of the statues of Putin.[11] In the popular comic series “Superputin”, which appeared in 2011, the president was saving the world a-la Daniel Craig (again wearing his judo-kit) against various enemies. Another attire in which the president is depicted is the ancient Greek Chiton or the Roman Toga, which bring him visually closer to the ancient roman emperors or mythological heroes like Heracles. Finally, the current Moscow art exhibition focuses on various depictions of Putin (who appears in various clothes: from a Santa Claus costume to medieval armor).

[1] Vyshyvanka: Ukraine's national costume conquers the catwalk, in: Fashion United.

[2] Wasko, Andrzej, Romantyczny sarmatyzm: tradycja szlachecka w literaturze polskiej lat 1831-1863, Arcana: Krakow, 1995, Grzybowski, Stanislaw, Sarmatyzm, Krajowa agencja wydawnicza: Warszawa, 1996.

[3] Bauer, Anna Maria, Moda na czarną biżuterię, Niepodległość i Pamięć 21/1-2 (45-46), 53-72, 2014.

[4] Wandycz, Piotr, The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1815, University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 1996, 257-258, Грицак, Ярослав, Іван Франко – Селяньский Син? Україна: культурна спадщина, національна свідомість, державність, 15/2006-2007.

[5] Забозлаева, Татьяна, Мода как политика в Российской империи, Чистый лист: Санкт-Петербург, 2013, 8-15.

[6] Ibidem, 8-51, Кирсанова, Раиса, Костюм — вещь и образ в русской литературе, Теория моды: одежда, тело, культура, N. 23, Весна 2012.

[7] О нас.

[8] Siehe die Website Miryanka.

[9] Siehe Путин на женской груди.

[10] Mona Al Mansouri star fashion show in Moscow, in: Daily Pegham; Kleid mit Putin schlägt Popularitätsrekorde, in: mk.ru.

[11] Tsereteli with His Controversial Putin Statue, in: The Urban Imagination

Zitation

Anna Novikov, Wearing the Motherland. The Revival of Patriotic/People’s Attire in the Post-Communist World , in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/wearing-motherland