Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) is an example of the director’s continued engagement with history on film. Rather than rehash older arguments from historians about Amistad’s historical (in)accuracies, this piece will reflect on a number of aspects I noticed upon rewatch in preparation for this article. For the first two-thirds of the film, Amistad largely avoids celebrating American values and instead emphasizes the nation’s flaws, particularly those related to chattel slavery. Once the action moves to the Supreme Court and John Quincy Adams, the film moves from stark realism towards a hokey celebration of the US Justice system and its founders and institutions—while a deeply flawed society, the US is, at the end of this film, not irredeemable. This attitude stands in stark contrast with more recent filmic depictions of chattel slavery on screen, most notably Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013). However, it is important to keep in mind the sociopolitical context in which Amistad was released. Produced in the mid-1990s, this film came out during the rise of the Newt Gingrich-led GOP, which took control of Congress during the 1996 midterms. In this sense, Amistad is also an alternative vision of Gingrich’s America: one which takes pride in how the country, in fits and starts, moved towards a more just multiracial democracy. Amistad is a profoundly optimistic film in this sense and fits with 1990s US liberalism, a response to conservative culture warriors embroiled in the “history wars” of the 1990s.

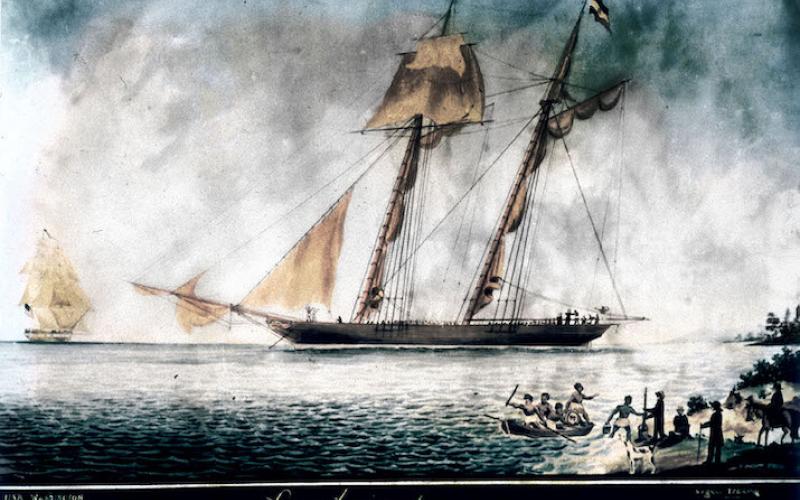

But the most striking aspect of Amistad upon rewatch was the film’s unflinching depictions of violence aboard the slave ship Tecora. Spielberg does not let the viewer look away—but this violence was not that of Jaws or his summer blockbusters. This was the unflinching brutality familiar to me from Schindler’s List. It seems to me that after tackling the Holocaust, which, we should all remind ourselves, was initially a passion project that Spielberg assumed he would lose money on, Spielberg wanted to turn to a dark aspect of American history. This is not to accuse him of equating the Holocaust with the transatlantic slave trade, but to point out that he followed an artistic trajectory similar to how the 1978 miniseries Holocaust was a direct artistic response to Roots—and both miniseries shared a director, Marvin J. Chomsky. It is perhaps not too farfetched to imagine that some of the artistic and ethical considerations Spielberg and Amblin Entertainment had to make on Amistad were informed in some way by their experience creating Schindler’s List.

Eric Foner has rightly pointed out that Amistad focuses too much on its white characters, though I would argue that Djimon Hounsu’s Joseph Cinqué is still the film’s moral center. While the decision to let the African characters speak in various West African languages, such as Mende, was arguably the correct one, the decision to leave this dialogue unsubtitled seemed anachronistic to this viewer. However, it is important to note that we cannot dismiss Amistad as simply a film made by a white man about the Black experience. This erases the deep involvement of African Americans at all stages of production. Debbie Allen was one of the film’s producers and her career consistently focused on depicting Black life in the US. She was one of the driving forces behind the production; she had sought to get a movie about the Amistad made since the 1980s. So, while this series focuses on Spielberg, it is important to move beyond auteur theory when discussing his films—they, as industrial products, are in the end collaborative enterprises.

Zitation

Nicholas K. Johnson, Amistad. Depicting Slavery during the 1990s , in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/amistad