The images are blurred and a bit chaotic, as they often are in on-the-spot videos of fast-moving events circulating on social media. But the gist of the story is clear. Three men clad in dark face masks and combat gear, their identities hidden behind their uniform exterior and emotionless body language, are rounding up a crowd of women. The women are fighting back, trying to break out of the cordon. Suddenly the three men in camouflage retreat. One holds his mask in his hand and looks distressed. They walk away quickly, the crowd whistles after them. What happened? The answer rests with a 73-year old great-grandmother who is a celebrity of the Belarusian protests. Fearlessly she demonstrates, scolds and sometimes kicks the security forces. And she always attempts to take off their masks—this time successfully. Belarusian security police do not like to show their face while shoving around women. And the Belarusian women know this. They have been coming out onto the street in ever increasing numbers to continue the fight against an entrenched dictatorship, inspired by their three female leaders, who are not career politicians, but ordinary women, some with husbands and children, all of them with aspirations.

In the following, three scholars have a look at the question of how to explain the female presence on the Belarusian streets and what it means both in the short and in the long term. The articles were written on the day of mass arrests of women in Minsk. The future is uncertain. Mass violence is on the cards as much as the possibility of a Lukashenko retreat. Whatever it will be, however, it deserves the world’s attention.

War does not have a womanly face, but protests do

Juliane Fürst

For weeks now, Belarus, a country virtually fully overlooked by the news most of the time, has been in the headlines, because of its citizens’ refusal to accept an election which was clearly fraudulent. As protests have run on, the issues have broadened from the desire to break Lukashenko’s twenty-six-year repressive rule to the whole canon of liberal demands: freedom of speech, press, religion, sexual orientation and culture, end of political incarceration, and the equality of gender. While many Western countries are battling populism and illiberalism, an Eastern European country has once again surprised the world by being out of step with the trend. Just as in 2014, when hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians went out onto the streets to ensure closer association of their country with the European Union, while the European Union was losing faith in itself over the Euro-crisis, now people in Belarus are defying violence and repression to fight for human rights at a time when elsewhere nationalism and misogyny trump liberal demands. Nothing has underscored this paradox more than the presence of so many (mostly young) female faces among the protesters, not least that of the three most prominent leaders Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Maria Kolesnikova and Veronika Tsepkalo.

The strong female presence in the frontlines of the protesters is all the more astonishing, since until recently Belarus, like many Eastern European countries, has been ruled more or less as a patriarchy both politically as well as socially. Lukashenko had no hesitation (and certainly no irony) when he declared earlier this year that a woman would be crushed under the burden of the presidency. That view is likely to be shared by a significant part of the male establishment in the country. When Belarus last saw large-scale demonstration during and shortly after Perestroika, women were conspicuously absent from the leading ranks of the liberal opposition and even more so from the ranks of the communist elite (from whose ranks Lukashenko rose). Just as in Russia, there have been no prominent female politicians since independence. The role of women remained circumscribed by definitions stressing family, motherhood, and caregiving roles. And even this time, it was supposed to be different. The frontline were supposed to be taken by Tikhonovskaya’s and Tsepkalo’ husbands, and by Viktor Babariko, for whom Kolesnikova worked. Is the female force in Belarus hence a fluke of history? An accident of circumstance?

From an historian’s point of view the roots of the ‘sudden’ female prominence lie both near to and further from the present. Like anywhere in Eastern Europe, but in particular in the Soviet Union, Belarusian women have always been a powerful force in carrying society through tough times, even if this force never translated into true political power. Seventy years of communist rule did not create female politicians, but it created a female workforce and a concomitant belief that women could and should work and hold rights associated in the widest sense with work. Belarus was one of the bloodiest battlegrounds of the Second World War, its cities and villages destroyed, its civilian population decimated and traumatized. It is no coincidence that Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexeyevich wrote her first book about the horrors the war inflicted on women in particular—War has no Womanly Face. Yet, like elsewhere, it was women who led the work of reconstruction with so many men dead and injured. Like elsewhere in the socialist world Belarusian women in the following decades carried the double burden of professional employment and domestic chores in a country which successfully emancipated women into the workforce but failed to address equality in the domestic sphere. And as elsewhere in the post-socialist world, it was often the women who carried families financially and mentally through the impoverished, tough 1990s, which in Belarus witnessed the creation of Lukashenko’s repressive rule and the establishment of a reactionary paternal conservatism.

Yet despite many signs to the contrary, Belarus did not get stuck entirely in a time warp. While the three female leaders found themselves spearheading a movement far larger than they ever anticipated through a confluence of accidents, the fact that these women were where they were—in the second row of activism—and that their calls for justice had such a resonance is no coincidence. The last thirty years did change things in Belarus, too. A younger, more globally orientated segment of society came to the fore, not least working in Belarus’ economic success story: the tech industry. Svetlana Alexeyevich was awarded the Nobel Prize, shining the spotlight back onto the oppositional intellectuals, who lost out almost everywhere in the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. ‘Me too’ had a more muted effect in Eastern Europe than in the West, but it spoke to a younger generation of women, who defined equality differently than their Soviet-socialized mothers did. When Lukashenko declared himself the winner with 80% of the vote many people in Belarus had enough. And it seems that women in particular had had enough. They had had enough of being repressed and paternalized. They had had enough of Lukashenko, the president, and Lukashenko, the man.

The group ‘Belarus Razam Berlin’, which organizes solidarity actions with the protests, is run by women. They are young—born after the Soviet Union fell apart. They call themselves feminists, but that is to describe themselves in Germany, not necessarily in Belarus. They are adamant that the protests are carried by men and women, but they admit that, following what is happening now, the position of women in Belarus will never be the same again. On their facebook-page, they quote Polish Nobel Prize Winner Olga Tokarczuk, who wrote that ‘a free Belarus will be a woman’. Looking at the pictures that are coming out of Minsk and other places, it is hard to imagine otherwise. Just as I am writing these words, on 19 September, news tickers across the internet report that hundreds of women have been rounded up and detained by security forces during their latest march of protest. 73-year old Nina Baganskaya, like Alexeyevich, a veteran of previous protests for freedom, has risen to cult status through her fearless confrontation with police. Her tiny frame and advanced age make it hard for the sturdy policemen to manhandle her in front of crowds. Even Lukashenko knows that the future belongs to the Belarusian women, because he is now organizing his own female events, where people wave his red and green flag, not the old red and white banner that has become the symbol of the protest movement (and not for the first time).

It is a hard task for a moustached man, who like Putin has built his presidency on a certain version of no-nonsense, no-empathy, bullish masculinity. Facing him armed with machine guns and in camouflage (as photographed not long ago when he exited the presidential helicopter) are thousands of women clad in white, speaking not only to associations of innocence and virginity but also to the image of rodina mat’—the motherland—strongly promoted during Soviet times, the suffragette movement and, of course, Belarus, which translates as White Russia. Valeryia Losikava and Sophija Savtchouk, the two young women leaders of Razam Berlin, see the presence of women on the street first and foremost as a tactical move. The paternalism that stifles Belarusian women is turned into a strength. Police forces are not accustomed to arresting and beating females. The presence of family on the streets unnerves them. This might be changing now, since order has clearly been given to show no more gallantry. But it will be a stress test for those forces loyal to Lukashenko—and one which might ultimately be won by the women.

Valeryia Losikava and Sophija Savtchouk play down their own significance as supporters and organizers in the diaspora. Yet they are the free, female Belarus Tokarczuk is talking about. Losikava describes the events as a quasi-rebirth of her own self from a person without a homeland into someone who feels pride in her own people. Savtchouk confirms their exile status as women who would like to go home, but only if their homeland allows them to be what they have become—global citizens with rights. There is a lot of pain—past and present—in their words, when they speak of the disappointment of their own people, who for so long let themselves be exploited, and now worry about their homeland, which has become another test case for the struggle between state and street. But there is also a lot of joy. “I was happy seeing these women leaders”, Losikava said several times.[1] They made her feel that she had a home again. Not only because they protested, but because they did so not as women playing men’s parts, but as women with justified emotions and finding strength in their womanhood. It is hard to imagine that Belarusian society will ever be the same after these emotional weeks no matter the outcome of the protests. And the changes will ripple through Eastern Europe as a whole.

"Your heart is a muscle the size of your fist"[2]

The promise of the Belarusian protest movement

Anika Walke

Heart, fist, victory sign—Svetlana Tikhanovskaya’s campaign logo is memorable for its hip design and for taking major parts of the Belarusian population, and the global social media circuit, by storm. The three signs, displayed by presidential candidate Tikhanovskaya, Veronika Tsepkalo, and Maria Kolesnikova during their joint rallies, were a refreshing intervention in Belarusian politics. Since the late 1990s, Belarus has been widely known for the authoritarian leadership of the beleaguered, (still) sitting president on the one hand, and a splintered opposition that has been systematically destroyed and largely unable to gain any substantial ground on the other. However, Tikhanovskaya’s campaign reflects a changing Belarusian society, a society in which in the past decade or so a growing number of especially 20 to 50-year-olds have laid the foundation for what the wider world now encounters for the first time. Citizens from all walks of life have built what is commonly referred to as a civil society—a network of organizations, group, and initiatives that address issues such as domestic abuse, environmental pollution, state neglect of people with disabilities, discrimination of the LGBTQ community, and, most recently, protection against COVID-19. Artists, performers, scholars, and educators, many of them women, have created a lively cultural scene outside of the state-supported cultural institutions, displaying immense creativity and persistence in shoring up the resources to reach a growing audience. The necessity for self-organization and mutual aid as well as the ability to access critical perspectives on society have encouraged and empowered the population to recognize and criticize the flaws and failures of state institutions. These tendencies facilitated the emergence of a mass movement that was more than willing to rally behind Tikhanovskaia. It was also this parallel society that gave rise to the campaign with its distinct look and appeal—hundreds of others could have stepped up in a similar way. Does the campaign offer a glimpse of what a new Belarusian society could, indeed, look like?

One might think that Tikhanovskaya’s candidature mirrors the dreadful events of the 1990s, when several opposition activists disappeared and, presumably, were killed on official orders. The wives of, among others, Gennadi Karpenko, Yury Zakharenko, Viktor Gonchar, Anatol Krasovsky and Dmitry Zavadsky, travelled to several European countries to call on respective governments to respond to the political murders in Belarus. Tikhanovskaya ran for office during the 2020 election because her husband was imprisoned for doing so, Tsepkalo’s husband was excluded from the ballot, and Maria Kolesnikova had worked for another, now also imprisoned candidate, Viktor Babariko. Beyond this parallel of women taking the lead after men are undermined, however, nothing is the same. Tikhanovskaya, often viewed as an “accidental leader,” injected the growing opposition to the authoritarian leader with energy precisely because she was like anyone else who was dissatisfied or who was being harmed, ostracized, or isolated. The campaign thus morphed into a mass movement for whom the combination of fist and heart, of courageous struggle, compassion and care for each other, promised the defeat of the hated status quo.

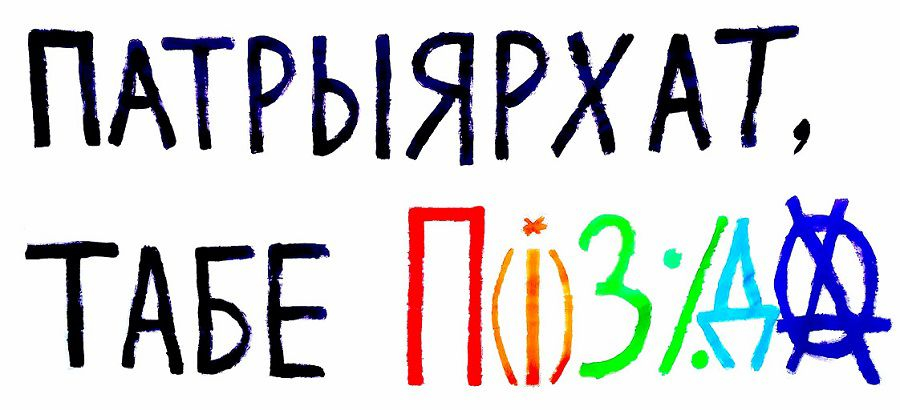

Earlier this year, the sitting president’s comments that women would be crushed under the burden of the presidentship enraged thousands, particularly women, and fueled the success of Tikhanovskaya’s campaign as well as of feminist positions.[3] This rage is also one of the driving forces of the recent Women’s Marches in Minsk, as well as many other marches and mass rallies around the country. Whereas the first of these marches were primarily addressing the brutal violence against protesters who took to the streets in the aftermath of the fraud election, subsequent rallies and activities have begun to look beyond the current moment and the calls for free elections, the release of all political prisoners, and the liberation of all protesters who have been jailed recently. In more and more neighborhoods around the country, people begin to organize support groups and festivals, as well as develop other forms of engagement that model a society built on principles of mutual recognition and equality. Posters at rallies call for an end to domestic violence against women or for the recognition of women’s labor, thereby calling out the patriarchal hierarchies and the conservative sexism that are pervasive in Belarusian society. Members of the LGBTQ community have taken to openly display rainbow flags at the marches and demand an end to homophobia. Many of them cite specifically an interview with Maria Kolesnikova in which she indicated that she may engage in romantic relationships not only with men, but also with women, as a moment that indicated to them a new era.[4] (Whether Kolesnikova indeed outed herself here or not is irrelevant, the fact that her statement was published with this possible interpretation and not immediately challenged does indeed signal an important shift.) And while responses to these calls for more openness toward queer lives are mixed, ranging from applause and active support to angry calls to shut up or demands to postpone “this discussion” so as not to hinder the fight for free elections and a free Belarus, there is more of a national conversation than there ever has been.[5]

The true test, however, for realizing the goal of a free and democratic society in Belarus will be the ability of the new society, which is currently emerging in the streets and neighborhoods of Belarus, to overcome entrenched and violent hierarchies and to care for each other across differences. Struggle and victory cannot be successful without empathy and the mundane labor of looking out for each other. Belarusian history has demonstrated this time and again, and it was usually women who secured survival, be it during World War I, the German occupation during World War II, or during the long postwar period of rebuilding and recovery. May the heart, so prominently shown by the now imprisoned Maria Kolesnikova, continue to help guide the movement for a free Belarus.

The Gendered Dystopia of Belarusian Protests

A discussion of the crackdown on the women protesters in the wake of the pro-government forum ‘For Belarus’ which took place on September 17, 2020

Sasha Razor

With thousands of female protesters taking to the streets after the fraud election that took place on August 9, 2020, the women of Belarus have transformed themselves into the newsmakers, the country’s info-export. As we browse and admire the beauty and vigor of these women’s marches covered by Reuters, BBC, Time, the Guardian, and the Atlantic, among other prominent Western media outlets, it is crucial to understand the reality behind these glossy protest images.

I began to fear that the regime would start coming after women and children as early as the end of August when I was watching videos of singular arrests of young women or of police agents in civil clothes harassing and videotaping a mother with two toddlers in the center of Minsk. Then came September 1, 2020, the first day of school in Belarus, when even more shocking videos were released with the police brutally arresting the university and BSU Lyceum students while their mothers and grandmothers were watching helplessly, unable to do anything about it. Another outrageous video documented the OMON harassing mothers and their elementary school-age children as they were celebrating their first day of school in a park in the city of Zhоdino, the place known for BelAZ plant that produces the world’s largest dump trucks and a pre-trial detention center.

It was around the same time that the regime started to co-opt the women’s protest, circulating the reportages about the female members of the OMON in the state media.[6] Images of corrupt teachers, female state officials, university administrators, and hateful female pro-government protesters flooded the Telegram news channels alongside the disturbing rumors that Russia supplied Lukashenko with the new detention vehicles for mothers with children and people with disabilities. The cooption operation culminated in the Women’s Forum ‘For Belarus,’ which took place on September 17. Thousands of women were bused to ‘Minsk-Arena,’ the country’s largest indoor venue, to chant out of tune and listen to the stately pop concert sprinkled with official addresses. The speech of the black-robe-clad Orthodox Hegumen Gavriila who condemned all protesters as the infernal sectarians became the epiphany of sorts.[7] The official crackdown on the female protesters offset on September 19, when 430 women were arrested during Women’s March. Albeit 385 protesters were released shortly after, this became the first instance of mass detentions of women in Minsk.

By mid-September, Belarus’s gendered protests are rapidly transforming into a gendered dystopia, starting to resemble even more The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), the bestselling novel by Canadian author Margaret Atwood that is now resonating in many corners of the world. Women like Maria Kolesnikova are being kidnapped on the street and, after a failed attempt to stage her fleeing the country, incarcerated. Women like Svetlana Alexievich are summoned for interrogation and harassed by the security services in her own apartment. Women like designer Nadezhda Zelenkova are being framed for participating in the anti-government activity while her husband, businessman Alexander Vasilevich, is already serving his eighteen-month prison term for merely articulating his civil position. Virtually any woman can be now punched in the face by the police for documenting the arrests. And it might be not too long before the select female protesters, like activist Elena Lazarchik, would be separated from their children.[8] Belarus even got its own Aunt Lydia––Lydia Yermoshina, the Chairwoman of the Central Committee of the Republic of Belarus, responsible for the election fraud. As Lukashenko threatens to close the country’s borders, and the internet remains an unstable entity, a new face-recognition database is being created to implement the total surveillance of the population.

Being a female protester in Belarus has never made anyone automatically immune to the state violence. Instead, it fell heavy on women’s shoulders: how do you run your household and, if you have children, parent and provide for the family in the crisis economy, while going to protests, facing police brutality, and doing volunteer coordination work? All the while, these women deal with the oppression that comes not just from the state or the patriarchy, but from the members of their own gender standing on the opposite side of the barricades. While there is little hope that the men supporting the regime will yield to the protesters, the sooner the women of Belarus find common ground, the sooner the state violence will come to an end, hopefully eliminating the source of its origin altogether.

Mehr dazu:

Sylvia Sasse, Briefe an Swetlana Alixejewitsch, in: Geschichte der Gegenwart vom 20.09.2020.

[1] Interview mit Juliane Fürst, 19.09.20. Unter freundlicher Genehmigung der Interviewpartnerinnen.

[2] Dalia Sapon-Shevin, Artist, 1999.

[3] TUT.BY, “Ona rukhnet, bedolaga", 20. June 2020; – The Bell, Interview with Maria Kolesnikova, 3 September 2020.

[4] The Village, Interview with Maria Kolesnikova, 27. August 2020; Hrodna.Life, Diktature strashnee gomofobii, 7. September 2020.

[5] See the screenshots of tweets included in the public Facebook post by Nick Antipov, 6. September 2020.

[6] See the article published by Hrodna live about the two female OMON employees who beat up the fifty-five-year-old woman; September 4. 2020.

[7] Orthodox Hegumen Gavriila speaks at ‘For Belarus’ Women’s Forum, September 17. 2020.

[8] See the article about activist Elena Lazarchuk’s son being taken away and placed in the orphanage after she failed to pick him up from school while being detained herself, September 18. 2020.

Zitation

Juliane Fürst, Anika Walke, Sasha Razor, On Free Women and a Free Belarus. A look at the female force behind the protests in Belarus, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/kommentar/free-women-and-free-belarus