Thirty years ago, the Bosnian Serb Army under the command of General Ratko Mladić overran the UN Safe Area of Srebrenica, starting the largest single mass killing on European soil after World War Two. The victims were unarmed civilians: Internally Displaced Persons from eastern Bosnia, who had fled their villages due to the Serb ethnic cleansing operations at the start of the war (1992). They took refuge in the Muslim (Bosniak) enclave of Srebrenica. From 12 July 1995 onwards, Bosnian Serb units executed more than eight thousand Bosniak men and boys, at killing sites across Eastern Bosnia, depositing their bodies into mass graves, subsequently disinterring and reburying them into new mass graves to cover up the crime.

Srebrenica now stands for the worst war crime in Europe after World War Two. In 2004, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ruled in a final decision that this constituted a genocide, the first in Europe after the Holocaust. Last year, the UN declared 11 July as the annual ‘International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica’, also condemning any form of genocide denial. The resolution encountered fierce opposition in Republika Srpska and Serbia, where genocide denial and the glorification of perpetrators are still the order of the day.

The Srebrenica Resolution is an important step: an annual commemoration is the least we can do as a sign of genuine humanity and act of solidarity with the survivors who must live with the insurmountable loss, the pain and trauma ever since. It is also instrumental in countering the ongoing genocide denial of (Bosnian) Serb politicians and public figures. Their point of view that this was a war crime but not a genocide is half-hearted and disingenuous, as they continue to celebrate the key architects and perpetrators of what they themselves declare to be a war crime.

The role of the Netherlands

The Netherlands played a key role in Srebrenica: A Dutch UN battalion was there to protect the UN Safe Area when Serbs took the enclave, not offering much resistance and assisting the Bosnian Serb Army. This made Srebrenica into the most controversial episode in the country’s recent history. Facing one scandal after another in the Dutch media, the Dutch government under Wim Kok commissioned an investigation that was carried out by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) in Amsterdam. The goal of the Srebrenica Research Team was to elucidate events in Srebrenica and the role Dutchbat had played. As an anthropologist, I was tasked with offering an understanding of the local dynamics that contributed to the massacre.

Despite its many shortcomings, the investigation was a remarkable contemporary history project that had a huge impact: six days after the NIOD published its report, the Dutch government saw no other option than to resign.[i] As is to be expected, the report was criticized and controversially discussed, by the survivors for example, who characterised it as a whitewash exonerating Dutchbat. Others took issue with the report’s condemnation of politicians occupying the moral high ground and being unconcerned with the consequences of their decisions (to send Dutchbat out on an ‘impossible’ mission), or the assessment that realistically Dutchbat could not have done much to stop the Bosnian Serb take-over and protect the Muslim population.

Was the massacre predictable?

On 10 April 2002, the director of the NIOD Hans Blom presented the conclusions to the Dutch government and media. Not all conclusions, however, were shared by the team members, as transpired months later from an investigation by the Dutch quality newspaper NRC Handelsblad.[ii] One issue that played an important role, at least for me, was that of responsibility and foresight, both on the part of Dutchbat and the UN. I will exemplify this by focusing on the situation on the ground as Dutchbat soldiers started to assist the Bosnian Serb army to separate men and women. The question was: could they have known or anticipated that they were assisting in a massacre or genocide? The NIOD director Hans Blom (and some team members) said no to this: it was impossible to imagine this kind of outcome, meaning that Dutchbat could not be blamed. I think, however, this can be fundamentally challenged. Another way of looking at it is that, yes, Dutchbat (or the higher Dutch and UN echelons) could not have predicted the future, but they at least should have acted on the premise of a worst-case scenario. In my view, they could have assumed that a massacre could take place as it was an imaginable sequence of events the moment they decided to participate in the separation of men and women.

If one of the possible and imaginable scenarios is indeed large-scale violence of whatever scale or scope, bystanders have the moral obligation to anticipate it and act accordingly. Most Bosniaks sensed that something terrible was awaiting them, based on previous experiences and an intimate historical and cultural knowledge of the local conditions. There had been some warning signals before, and even if it was hard to interpret alerts because of their ambiguous nature, it is nevertheless possible to imagine such an outcome. Dutchbat should and could have had some premonition because so many men and boys tried to escape through the forests as they thought this was their only hope of survival. Most of those who did not join the column and went with their families to the UN base in Potočari did indeed not survive.

Not anticipating worst-case scenarios means closing one's eyes for the potential consequences of (in)actions: it is indeed a common response for bystanders to look away and downplay the potential risks.[iii] Being perceptive to the fear that reigned around the UN base, Dutchbat could have done something to prevent these worst-case scenarios materialising but did not do it. They were complicit, as bystanders, for what happened, not because they carried out the massacre – the Bosnian Serbs did that – but because they failed to do what was in their limited power to protect Muslim civilians. What preceded this was a process of gradual withdrawal of empathy on the part of Dutch troops from the destitute victims of Serb nationalist designs.

Srebrenica and Gaza

Looking back, it is hard for me not to see parallels with ongoing events, to be more precise, Israel’s war in Gaza. I am inadvertently reminded of Srebrenica when seeing what is happening there. As I wrote before, I cannot help but see the similarities – like genocidal intent, the deliberate starvation of civilians, the calculated creation of unliveable circumstances, the planned expulsion or extermination of the population, etc.[iv] I am beyond the point that I am cautious about using the g word – this was last year – as worst-case scenarios have become true in the meantime. A plethora of international and human rights organisations (UN, MSF, Amnesty International, the IRCR, etc) have been consistently ringing the alarm bells, but much of the world has been looking away, foregoing their obligation to act on Israel’s openly communicated war goal – condoned by the Trump administration – for a fully-fledged disposal of the Palestinian population. There are many signs on the wall that are much clearer than they ever were in Srebrenica, where it only started transpiring after the fall of the UN Safe Area that hell had come down on Bosniak men, boys, and their families. It took another nine years of due judicial process to qualify the Srebrenica massacre as a genocide.

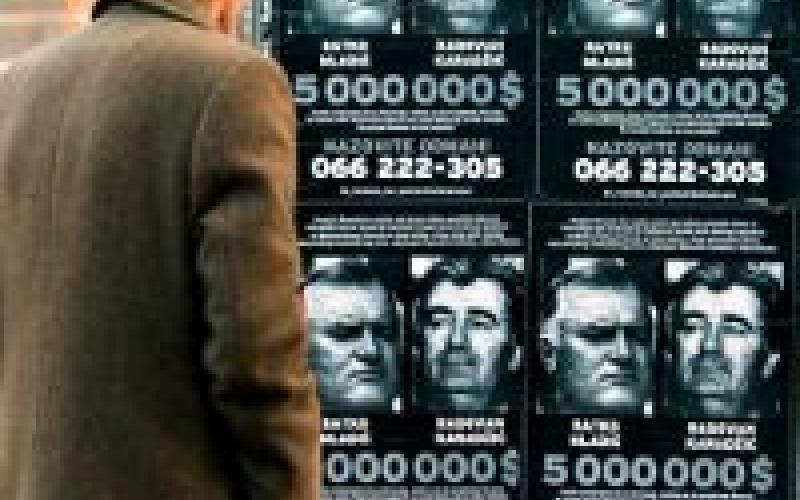

Let me not leave unmentioned the specific lack of response that I encounter here in Germany. I find the German indifference about the now almost 60.000 Palestinians killed shocking. It is gruesome that this is justified with reference to Israel's right to defend itself, Germany’s historical guilt and the near complete self-identification with Israel’s security agenda – oblivious of its consistent racist and far-right policies – as part of Germany’s Staatsräson. The prevalent indifference amongst political and academic elites shows that they have accepted the systematic dehumanization and elimination of Palestinian civilians as a necessary evil. It has been gut-wrenching for me to see that after months of blocking humanitarian aid, preceded by the destruction of homes, infrastructure, and hospitals, Israel was finally willing to hand out a bit of 'aid', using the opportunity to shoot hundreds of destitute people that just come to pick up that aid. It reminds me of General Ratko Mladić handing out sweets to children on 12 July 1995, in front of rolling cameras, then executing their fathers and brothers the next day.

Germany’s elites seem to have lost their moral compass, like Israel’s government and a large part of the country’s population, as the Dutch Israeli anthropologist Erella Grasiani has compellingly argued.[v] Germany's blurred view can only be explained by the fact that it has learned, like no other country, to look away when serious crimes are committed.[vi] Germany is Weltmeister in Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung (the world champion in working-off-the-past), but it is also, at the same time, and even more so, Weltmeister in Verdrängung (the world champion in repression, in the Freudian sense). It is reigned by a culture of ‘neglect’ (or ‘silencing’), of not responding when crimes are committed: is that not reminiscent of a previous era in German history? Some Germans may think that Gaza like Srebrenica is only a ‘small’ genocide compared to the Holocaust – but that does not alter the fact that Germany carries a direct responsibility, drawing the wrong lessons from its history, unconditionally supporting Israel while being uninterested in the plight of the Arab population.

Dark emotions

As I argued in a recent revision of my work on Srebrenica, communities that regard themselves as victimized can cultivate their victimhood status with such intensity that they can become perpetrators of heinous crimes.[vii] As I showed for the Serbs, it is indeed not unlikely for victims (real or self-styled) to become perpetrators. What drives them are ‘dark emotions’, which constitute an invitation, often collectively framed, to undo the humiliating status of victimhood, justifying acts of revenge and retribution, and releasing energies to take collective remedial action. That is why the perpetrators of genocidal violence often present themselves, in the first place, as ‘victims’ and not as perpetrators.

What also connects Srebrenica and Gaza is the fact that Muslims carried out attacks on Serb villages around Srebrenica (in 1992-93), respectively on Israeli settlements (the Hammas attacks on 7 October 2023). It is clear, people were brutally killed and massacred in these attacks, but it does not give the Bosnian Serb Army, and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) the licence to kill indiscriminately, not distinguishing between civilians and combatants. The attacks on Serb villages helped to create an image of a ruthless Muslim enemy that needed to be eradicated once and for all, and the same seems to happen for Hammas and Gaza’s Palestinian population. General Mladić’s call to build a ‘winning army’, creating new realities on the ground, claiming territories and removing others (if need comes by killing them), is matched with what Israel has been doing in Gaza, with the political and military support of the US and Germany. There seems to be little hope for Palestinian survival, let alone a durable peace and long-term societal healing, if the international community allows revenge and excessive and cynical retribution to continue.

[i] J.C.H. Blom et al. Srebrenica, een ‘veilig’ gebied. Reconstructie, achtergronden, gevolgen en analyses van de val van een Safe Area. Amsterdam: Boom, 2002. For the authorised online English translation see: https://www.niod.nl/en/publications/srebrenica.

[ii] Bas Blokker. NIOD oordeelt niet unaniem over Srebrenica. In: NRC Handelsblad, 9-10 November 2002, 1 and 23-24.

[iii] Catherine A. Sanderson. The bystander effect. The psychology of courage and inaction. London: William Collins, 2020.

[iv] Ger Duijzings. Srebrenica (never) again? Responding to the Bavarian Action Plan against Antisemitism, seeFField Blog, 30 October 2024.

[v] Erella Grasiani. Radio-interview and podcast: Het morele kompas van Israël is afwezig. VPRO, Het Marathoninterview, NPO Radio 1, 26 December 2024.

[vi] Susan Neiman. Learning from the Germans: confronting race and the memory of evil. Penguin Books, 2020.

[vii] Ger Duijzings. Perpetrators as 'victims' in eastern Bosnia (1992-1995): towards an anthropology of dark emotions. In: Harriet Rudolph and Isabella von Treskow (Hg.), Opfer: Dynamiken der Viktimisierung vom 17. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2020, 259-279.

Zitation

Ger Duijzings , Srebrenica 30 years later. Are there lessons to be learned?, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/srebrenica-30-years-later