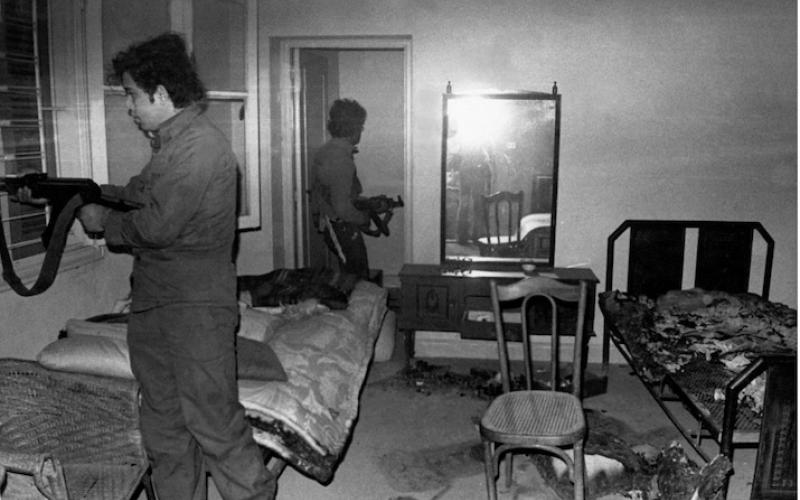

On October 7, 2023, I woke up at 6:30 am with my two-year-old son, when a jarring message pierced the quiet morning: a neighbor on our community WhatsApp group inquired about the key to the public shelter. My heart pounded as I reached for my phone, a news app already opening. The headline was a picture of a tender in Sderot, a western Negev city, overflowing with what seemed like at least ten armed terrorists. Mere seconds later, the wail of air raid sirens shattered the fragile peace.

With no designated safe room, our family huddled together – my husband, myself, and our two young sons – in a cramped hallway. Time seemed to warp; minutes stretched into an agonizing eternity. As the initial shock subsided, I reached out to our tenants in Ofakim, a southern city, only to be met with a devastating truth: while they were safe, some of their friends had been tragically killed. It was only 8:30 am, the day still young, yet already stained with loss. The following hours were a blur of frantic calls and a relentless stream of social media updates. Friends caught in the crossfire at the Nova music festival documented their terrifying escape online. Others, desperate for news of loved ones, flooded online platforms with pleas.

As an oral historian, well invested in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and with years of experience in collecting testimonies from Holocaust survivors, refugees, and asylum seekers, I honed a unique skillset. Now, in the face of the brutal reality, this expertise has become highly relevant. At the time of the events, I was the head of the Oral History Division at the Harman Research Institute for Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Immediately after the attack, I was contacted by numerous individuals and organizations – all eager to document the stories unfolding around us.

My initial instinct was to hesitate – how could anyone expect to interview the deeply traumatized survivors so soon, especially while the war raged on? But there was also a quick realization that people are not waiting for my professional approval. Many documentation initiatives have begun to appear, mostly by citizens, who wanted to document the historical moment. I soon realized that I could either sit on the sidelines, pondering the enormity of the task, or actively contribute.

Two weeks later, I joined forces with five other oral history and documentary professionals to create the FORUM FOR WARTIME DOCUMENTARY INITIATIVES.[1] Our mission: to create a community of documentarists to share resources, foster collaboration, and empower the numerous initiatives capturing the ongoing war. Launched on October 24th, 2023, the forum has become a vibrant community of more than 350 members, representing over 100 documentation projects. We bring together a diverse network of experts – filmmakers, archivists, historians, memory scholars, and more – to streamline the documentation process and ensure wider accessibility. The guidance and advice are provided via the forum's WhatsApp group, through personalized consultations for initiatives requiring assistance, as well as through professional Zoom meetings held weekly during the first six months of the war, based on the needs expressed by the documentation community.

As an inclusive community, we welcome efforts to capture every aspect of the war. Thus, alongside initiatives documenting the experiences of victims and survivors, there are also initiatives focusing on documenting the experiences of various sectors of Israeli society during the war, such as evacuees from the north and south, military personnel, police officers, diaspora Jews, asylum seekers living in Israel, aid workers, educators, volunteers, and more.

In addition to oral history initiatives, the Forum supports projects collecting online videos, self-documentation platforms, and preserving WhatsApp messages from communities and individuals affected by the events of October 7. Other initiatives gather materials from social media through data scraping, digital donations, and advocacy organizations. The Forum also backs documentary films and series, podcast projects, and object preservation. Several initiatives focus on public spaces—documenting funerals, eulogies, the hostages' families' struggle, and public stickers. Severla initiatives specialize in still photography, one maps victims' names and locations, and a few created 3D documentations of destroyed houses.

Having worked extensively with testimonies of Holocaust survivors and asylum seekers, I quickly recognized the emergence of both civic and institutional initiatives that leverage oral history as a powerful tool for psychological and social identity construction and rehabilitation. I also noticed that many of these survivor-focused efforts are rooted in trauma documentation methodologies developed over the years to capture the experiences of Holocaust survivors.

In Israel, the effort to document Holocaust testimonies began during World War II and gained momentum with Yad Vashem's Holocaust Documentation Project in 1945. After the war, additional initiatives joined this effort, including those led by the Ghetto Fighters' Organization, Yad Vashem, and the Eichmann Trial, where survivor testimonies were systematically collected.[2]

The pioneering practitioners of oral documentation in Israel saw before them the goal of completing and clarifying the existing written documentation. The concept underlying the development of the field was that the systematic collection of documentary and audio materials would become a critical mass when researchers would come to deal with topics where the scarcity of documentary materials could be an obstacle to in-depth research.

In 1979, the first project to document Holocaust survivors using video was established at Yale University, becoming the opening shot of a new era that seeks to place the witness at the center, in the face of the commodification of the Holocaust on the one hand and the emergence of a new wave of Holocaust deniers who sought to cast doubt on the testimonies of the survivors on the other. Dori Laub, an Israeli American psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst, a trauma expert and researcher of testimonies, from the Yale University School of Psychiatry, was one of the founders and initiators of the Fortunoff Archive - the world's first archive of Holocaust survivor video testimonies. Based on his experience interviewing hundreds of survivors, he developed interview techniques that help witnesses bear their testimony and cope with the trauma. [3]

In the first days following the October 7th attack, a group of Israeli documentary filmmakers, scholars, and mental health professionals started to collect video testimonies from survivors. Named Edut 710, for the Hebrew word for testimony, this project seeks to build a large video archive to document and preserve witness accounts of this terrible event and its repercussions. From the beginning, the team behind Edut 710 looked to the Fortunoff Video Archive in general, and the approach of Dori Laub in particular, as a model for documenting witness accounts of mass violence on video. This project documented over 1000 testimonies so far, focusing mainly on first-hand survivors of the attack.[4]

Another oral history initiative with a similar approach is the USC Shoah Foundation which within weeks of the brutal attack, began conducting interviews with survivors and witnesses. The foundation was established by Steven Spielberg in 1994 following the completion of his film Schindler's List and partnered with the University of Southern Carolina in 2006. The October 7 survivors' testimonies are part of the foundation's ongoing initiative to expand its Contemporary Antisemitism Collection focused on victims of antisemitism since 1945.[5]

Since the beginning of the war, the Forum has been working closely with the National Library of Israel to create a national database for all documentation materials. With a focus on the future preservation of all the collected material, the National Library has offered itself as the central repository for the dozens of projects now collecting documentation, including testimonies, audio/video recordings, online messages, press clips, and ephemera from social media, civil institutions, military, governments and more.[6] In collaboration with the National Library, the various documentation initiatives, trauma experts, legal specialists, and others, the Forum aims to establish ethical guidelines while developing the most effective, sensitive, and professional methods for documenting, collecting, and accessing information.

Another important task taken by the Forum arose three months ago when I received a phone call from a person who lost his daughter at the Nova music festival. He was part of a group of two hundred parents who lost their loved ones on October 7 and most of them have no information about their last moments. He asked me to connect him to the documentation initiatives with the hope that maybe some of the testimonies mention some of the victims from his group. This appeal raised significant ethical concerns about privacy rights, however at that time, it highlighted the urgent need to connect between the various initiatives, particularly those focused on collecting testimonies from survivors, and to create a list of people, groups, and communities who gave testimonies. For this aim, the National Library is leading a work group together with the Forum and the leading initiatives, to create a unified meta-data system for all the documentation materials collected by the different initiatives.

For me, this tragic conversation created an association from my research world - the Search Bureau for Missing Relatives after the Holocaust. This organization was set up by the Jewish Agency in 1951 to assist Holocaust survivors and to help reunite families that had been separated. As historian Tehila Darmon Malka argues, searching for relatives is, in fact, a basic and natural act that occurs after any catastrophe or disaster. Almost everyone's first heartfelt wish is to find out what happened to their loved ones and to see if they can be reunited with them, help them, or at least bring some peace of mind to their soul by knowing for sure that their loved ones are no longer among the living. However, in many ways, it is also a form of an alternative memory. In the post-war years, before the paths of Holocaust commemoration in Israel were fully established, and when the dominant tone in the discourse was of collective memory of strength and heroism, the Search Bureau was an act of commemoration.[7] October 7 was not the Holocaust. However, it is a national trauma marked by unimaginable personal tragedies. The documentation efforts, while formally recording the atrocities and survivor experiences, represent the first steps toward commemoration, as they shape the whys in which the event will be remembered.

In conclusion, the events of October 7 deeply shocked Israeli society, prompting the rapid organization of civil and institutional efforts to document the events in real-time, collect testimonies, and preserve collective memory. These grassroots initiatives exemplify civic activism, amplifying diverse voices and creating a complex narrative of the events. They offer a rare opportunity to explore how people reconstruct the past before a dominant state narrative emerges. The Forum for Wartime Documentary Initiatives was founded in this spirit, serving as a hub for these efforts. Documenting the October 7 attack is a crucial first step in commemorating the event, ensuring the voices of those affected are heard, and preserving these experiences as part of our national and civic heritage for a better future.

[1] The FORUM founding team includes Ruti Frensdorff (Independent documentarian and activist(, Sharon Rapaport (Independent documentarian and interviewer specializing in Trauma and immigration experiences), Peleg Levy & Eric Halivni (the founders of the Toldot Yisrael testimonies project), Dr. Margalit Bejarano (the director of the Israeli Oral History Association), and the author. To learn more about the FORUM activities see here.

[2] Gil, I. (2013). BETWEEN RECEPTION AND SELF-PERCEPTION: TESTIMONIES OF HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS IN ISRAEL. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 12(3), 493–515.

[3] Mucci, Clara. "Healing and forgiveness after traumatic events: The case of Holocaust survivors from the Fortunoff Archives." In: A journey through forgiveness. Brill, 2010. 109-117.

[4] For the website of Edut 710 see here.

[5] For interviews with survivors of the October 7 Attack see here.

[6] To read more about the National Library of Israel Launches Initiative to Preserve October 7 Massacre and War Documentation see here.

[7] Tehila Darmon Malka. "Who knows? – From relatives search in Europe to The Search Bureau for Missing Relative," ISRAELIS -Multidisciplinary Periodical in Israel Studies 3, 2011: 47-69 [Hebrew].

Zitation

Roni Mikel-Arieli , Preserving the Echoes. Trauma, Testimony, and the Vital Role of Wartime Documentation, in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/preserving-echoes