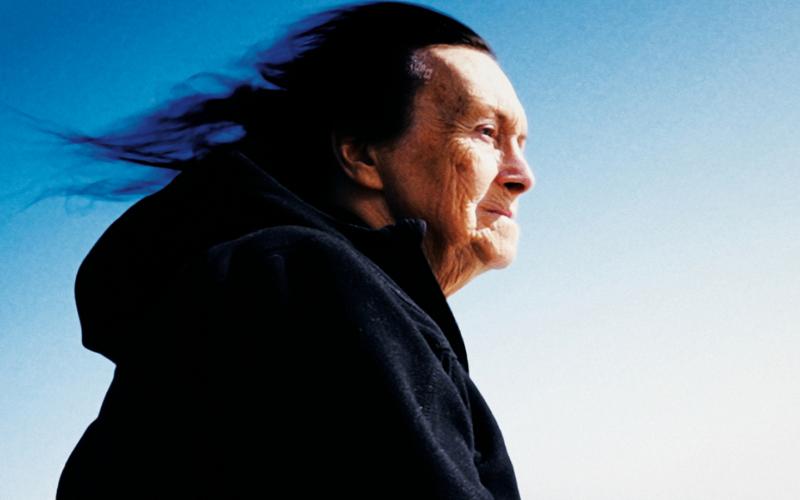

In August 2020, following what is widely considered a rigged election, Belarus erupted in protests. People took to the streets to oppose Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s sixth term as president and the general state of authoritarian rule in the country. Among those present was filmmaker Aliaksei Paluyan. He was making a documentary on the uprisings in Minsk through the experiences of Maryna Yakubovich, Pavel Haradnizky, and Denis Tarasenka, three residents of the city who are associated with the underground Belarus Free Theatre. The film, COURAGE, had its world premiere at the 71st Berlinale. Shortly after the premiere, I spoke with Aliaksei about the role of art in an authoritarian regime, his experiences of filming during the protests, and how he perceives the transformations taking place in Belarus.

Natasha Klimenko: Could you tell me about why you made this film?

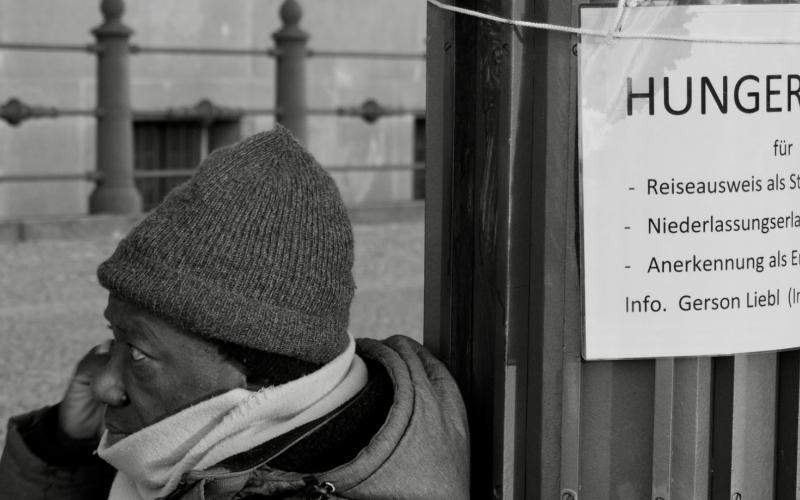

Aliaksei Paluyan: One of my goals was to look at artists in Belarus. I wanted to understand the role of an independent artist in an autocratic country, and what price independent artists should pay to be free — if freedom in this regard is even possible, or if this is a kind of utopia. Another goal was to amplify the political issues happening in Belarus. World media is no longer covering the election or the protests as much as it was in August, but nothing has changed in the country. The political crisis is not resolved. In fact, there is more oppression now. People are receiving jail sentences for nothing. They write graffiti and are imprisoned for five years, for example. This is an impossible situation. I want the political situation to be made more evident. I also wanted to give the audience the feeling that they are within a historical moment. That was my main goal, to bring the audience to Minsk in 2020, inside the events. I’m not certain that a lot of people, even in Europe, know about what’s happening, or, if you take North America, I get the impression that most people there don’t even know where Belarus is, to be honest.

Natasha Klimenko: Why did you make this documentary through the lens of protagonists associated with the Belarus Free Theatre specifically?

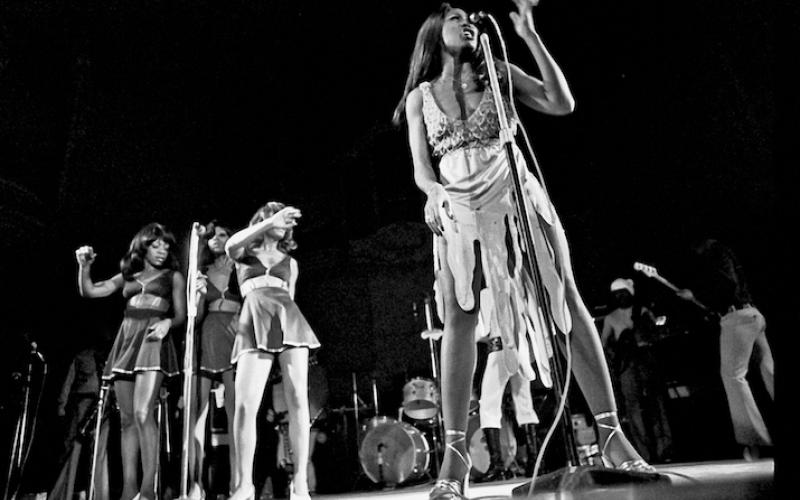

Aliaksei Paluyan: In 2010, when I was a student, I saw a performance by the Belarus Free Theatre for the first time and it left me speechless. It was a very underground theater. It was not possible to buy or reserve tickets in advance, you had to call some numbers, go to a semi-secret location in the middle of Minsk, and, in a strange building, there would be a stage and 30–40 places to sit on the floor. The performances were done with minimal theatrical elements, but they were so powerful, and the artists took up topics that no one else was publicly discussing — the death penalty for example, which is such a taboo issue, even today. I was really shocked. I wanted to make this film following actors from the theatre because I have the sense that artists have a podium. Other people are too voiceless in the crisis.

Natasha Klimenko: How do you see the role of art, including your film, in relation to the political crisis?

Aliaksei Paluyan: As a filmmaker, I believe that art and cinema have the potentials to change the minds of spectators. I’m trying to bring the truth of the political situation to an audience. I couldn’t say that that my film will help bring people to the street, or that these people will take down the system — absolutely not. I do however think it could give a new impulse to some viewers, and, if artists are continuously producing this type of work, it can accumulate the amount of people who become engaged. This is the most I can do. I’m not an activist, I’m a filmmaker. If I were an activist, I would be on the street right now, I wouldn’t be able to give this interview, I would likely be imprisoned.

Natasha Klimenko: You began working on the film before the election results. Did you anticipate the kind of protests and mass response that occurred?

Aliaksei Paluyan: I expected that there would be mass protests. It was clear in May and in June of 2020 that there will be a big wave of people on the streets in August. I remember feeling this intensely on the day of the election. There was an uncanny feeling on the 9th of August. I was driving with Denis down the main street of Minsk — Independence Avenue [Prospekt Nezalezhnosti] — and it was almost empty. The mood was grim, and I remember seeing a mass of soldiers, including many young recruits, behind the main theater, the Yanka Kupala. Some officers had German Shepherds, and it felt very symbolic. The dogs were on standby, seeming ready to attack. And this was only two in the afternoon. I had a very bad feeling that we would be hit with days of hell, and that’s what happened. But I was not surprised. My camera woman, Tanya Haurylchyk, and I were prepared for a brutal period.

Natasha Klimenko: What was it like to film during the protests?

Aliaksei Paluyan: It was very dangerous to make this film, and we were very lucky that we weren’t arrested, although we came close many times. There is a scene in the film with Pavel, on the day of election, where he is seen running from the protests. When he later calls the others he had been with, he finds out two of them had been arrested. We were about one hundred meters away from them, and had we been closer, we would have been arrested too, but we were lucky. I can’t answer how we managed to avoid arrest. At another point, we were near a water cannon and it was shot in our direction. Our microphone was destroyed, and the camera was affected too, and that was the end of shooting for the day. We had a feeling of fear every day.

Natasha Klimenko: How do you feel having made a documentary about protests and repressions in Belarus? And how do your protagonists feel being associated with the project?

Aliaksei Paluyan: I take a lot of responsibility on behalf of my protagonists. This is a dilemma for me. The film is meant to bring clarity to the issue, but the louder the film is, the bigger the problems that could potentially arise for the protagonists are. We’re currently in close contact with each other, and we are trying to find a solution for them. All of them could face exile, but at least they have this as a plan B. If they see signs that they could be arrested, they will leave. Pavel and Denis were in fact recently arrested during a performance of their band on the 13th of February and were released about three weeks later.

Natasha Klimenko: Why did they decide to keep their real names in the film?

Aliaksei Paluyan: They have been doing this for 15 years. This is not something new for them, and they stand behind their decision. They don’t want to hide, their art is a form of protest and they are open about it.

Natasha Klimenko: The city of Minsk and its architecture visually play a prominent role in the film, but this was not something that was explicitly discussed. What kind of stage is the city of Minsk for the protests?

Aliaksei Paluyan: I was thinking a lot about the meaning of the city of Minsk during the protests. I think there are two levels to the city and to the film. There is an underground level and another level above ground. The underground level is lively and energetic, this is the space of the theater and other art movements. Here, people can express criticism, this space is alive. The above ground level is the level of authority, and it is like a shop’s display window. The public space of Minsk is a liberal display window, created by the regime during the last ten years. Everything seems great, everything is perfect. Minsk is a hip, modern city, what more could you want? But it is not alive. This is a very pessimistic, emotionless, and controlled space. In August 2020, however, all the forbidden topics that people dare to think about only in their kitchens, in their flats — or in underground art spaces — were moved into the public sphere. A transformation happened during the protests. Hundreds of thousands of people showed up on the streets, and with them came issues not discussed in public. This transfer from the private to the public was very important.

Natasha Klimenko: Has this transformation also occurred on the level of identity?

Aliaksei Paluyan: I think a lot people have a new conception of what it is to be from Belarus, yes. There were protests in the beginning of the 1990s in many post-Soviet countries — in the Baltic states, in Ukraine, and in Belarus. Some of the protests began successfully in Belarus, but they were crushed when one person assumed power. People now have to continue the protests and I think this could lead to the creation of an independent Belarusian people, one that is no longer attached to a Soviet or a Russian identity. This is a very complicated topic. A lot of people began to conceptualize of themselves as Belarusian during the summer. Many also think that they can define the destiny of the country, and this is a new and a very active position. I appreciate this active position, it is one I want to portray.

Courage (Deutschland 2021)

Drehbuch und Regie: Aliaksei Paluyan, Produktion: Jörn Möllenkamp.

Dauer: 90 Minuten.

Theatrical release in Germany: July 1, 2021

Termine im Summer-Special der Berlinale:

11. Juni 19.00 Uhr im Freiluftkino Museumsinsel

13. Juni 22.00 Uhr in der Freilichtbühne Weißensee

Aus Anlass der Publikums-Premiere am 11. Juni kann man via Live-Stream der Podiumsdiskussion ab 15.30 Uhr auf Twitter (@HEBerlinEuropa) und YouTube (@HEBerlinEuropa) folgen. Der Film wird außerdem am 1. Juli in den deutschen Kinos anlaufen.

Zitation

Natasha Klimenko, Courage. Interview with Aliaksei Paluyan, Director of COURAGE, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/interview/courage