In the late summer and early fall of 2020, Belarus, a country otherwise absent from global (or even European) headlines, briefly appeared in the news. On August 9th, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, Europe’s self-proclaimed last dictator, declared his sixth term as president. Inside the country, much of the population considered the results rigged. Mass protests broke out across Belarus. The regime brutally repressed them. The population continued to resist. Although the events kept going Belarus receded from the international news cycle, back to relative obscurity.

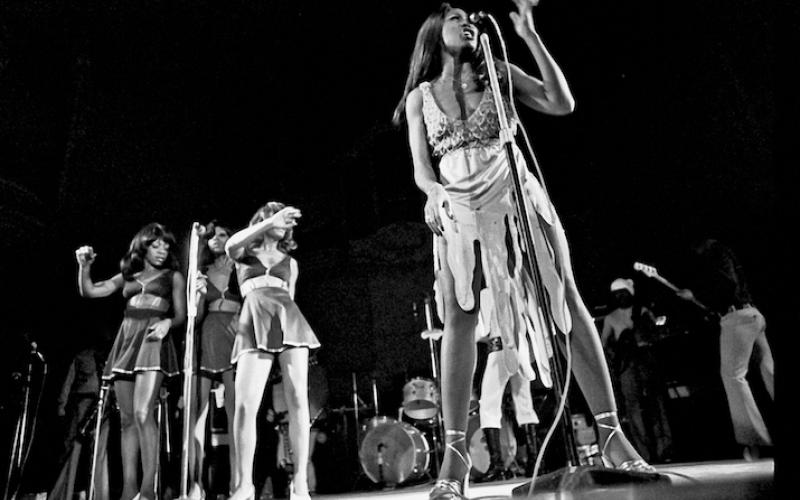

Aliaksei Paluyan’s documentary film COURAGE premiered at the 71st Berlinale in March of this year. The film looks at the Belarusian uprisings, yet unlike many of the fleeting images that circulated within social media and digital publications—police vans, marching women, the red and white colors of the oppositional flag—the film also portrays a more human side of the developments. It delves into the political complexities of the larger situation and, at times, into the ambivalences of those involved in opposition. Specifically, the film is set in Minsk, and follows Maryna Yakubovich, Pavel Haradnizky, and Denis Tarasenka, three residents of the capital who are associated with the underground Belarus Free Theatre. The film shows the demonstrations, accompanies the rehearsals and performances of the theatre company, and documents conversations with the three protagonists in their personal settings. These conversations are often edited to be delivered almost like monologues.

The Belarus Free Theatre, formed in March 2005, performs plays that address subjects that are otherwise censored in officially recognized theatre. The footage pairs the company with the election. While the theatre group tackles topics—such as corruption or the disappearance of dissident figures—that come closer to the political reality of the country, the official governmental processes engage in elaborate theatricality. Facticity and artificiality are reversed. The election can be taken as the pinnacle for the latter, which, although rigged, was performed as if truthful: Election booths were set up around the country, voters could cast their ballot.

Another reversal occurs in the film’s portrayal of Minsk’s urban landscape. Slogans in capital letters—like “The achievement of the people doesn’t die” (“Podvig naroda bessmerten”)—and murals proclaim the greatness of the Soviet subject. Palatial structures recall the Stalinist period. The wide boulevards suggest a space intended for grandiose gestures, such as military parades. On its own this landscape seems lifeless and almost ironic, a kind of museum of the Soviet past. Instead of serving as a display of military grandeur, the streets attain new meaning when flooded with protestors. The cliché of the “achievement of the people” is transferred into their living actions, rather than memorialized in tropes and stereotypes. Paluyan, however, does not dwell on the protests as solely forceful displays but also presents their peripheral moments. People stand around and wait, they exchange phone numbers and trade tips. There is a level of uncertainty. Some shots linger on the faces of police in riot gear. Although their faces are mainly covered, the features that can be seen reveal that many are young, and some seem afraid.

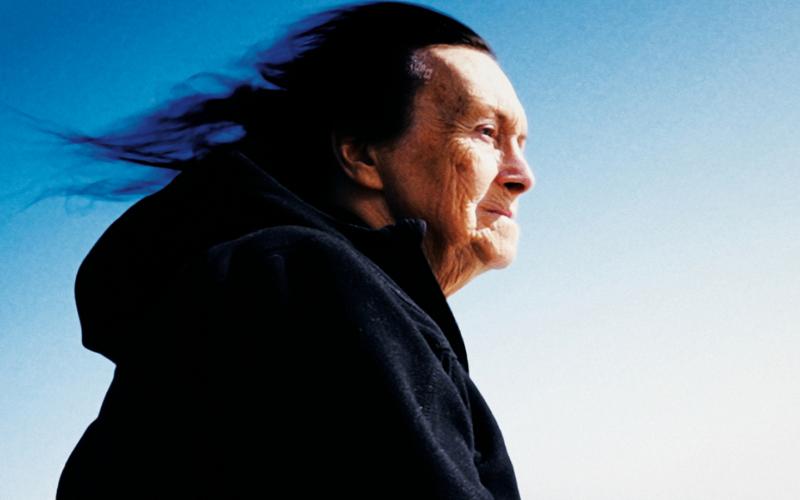

Beyond the larger congregations, in more reflective scenes that feature the protagonists alone, the mood shifts between resoluteness and wavering ambivalence. When Maryna is at home and talks to her partner, she questions the demonstrations, asking what would actually happen if everyone ended up on the streets and the police laid down their shields. Similarly, Denis—himself no longer working as an actor and now employed as a mechanic—expresses fear that the protests will only result in harsher repressions. Pavel’s doubts turn to theatre. He wonders if this is a moment where there is any need for art.

Despite the ambivalence, the theme of change is consistently present. The late-1980s song “[I] want change!” (“Khochu peremen!”) by the Soviet rock band Kino repeatedly plays in the film. The track, which became popular during Soviet independence protests in the early 1990s, both suggests a continuity with previous historical moments, yet, through its message, pushes towards a new future. The protagonists remark on the singularity of the events during the protests more explicitly. As Pavel suggests, they are making history. Denis states that if any transformations have occurred, they can only be seen in the intensified level of repressions, but even with this dark observation, he ends by suggesting that those resisting always think of something new. Yet the optimism is somewhat difficult to focus on, as he continues to describe the brutality enacted on people who have been arrested.

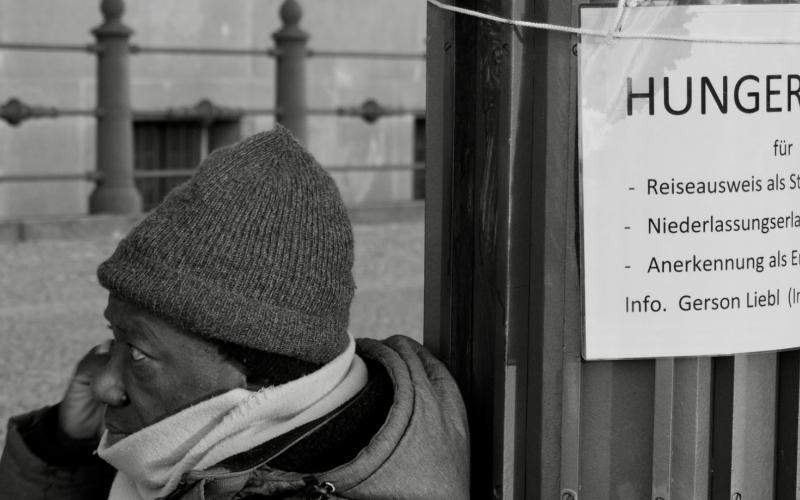

Paluyan himself is from Belarus, but he resides in Germany where he studied film and television production. In March of this year, when the film first screened—albeit, like much else in the world, digitally and mainly for press—I spoke to him about COURAGE. He told me that one of his goals for making the documentary was to amplify the political issues in the country. At the time of our interview, he stressed that, although global media had stopped covering the political situation, nothing had changed. Now, Belarus is once again present on the world stage. On Sunday, the 23rd of May, a fighter jet forced down a Ryanair plane, en route from Athens to Vilnius, while it passed over the country. Roman Protasevich, a Belarusian dissident living in exile in Lithuania, was on board. He was arrested and his partner, Sofia Sapega, also on the flight, was not allowed to reboard. The following Monday, the EU declared it would impose new sanctions, including the diversion of flights from Belarusian airspace and a ban on Belarusian airlines to fly over the EU or land in its airports.

The external sanctions placed on Belarus may pressure the regime, but they also effectively distance it from its western neighbors. Meanwhile, in early May, Lukashenka’s government began to silence artists and journalists. The internal repressions act to quiet opposition within the country. All this questions the prospects for positive change as the news of the Ryanair flight also slips out of international focus and takes news of Belarus with it. The new restrictions increase the urgency of COURAGE. The film becomes a document of a time when recording the protests, or engaging in cultural resistance, was more feasible.

Courage (Deutschland 2021)

Drehbuch und Regie: Aliaksei Paluyan, Produktion: Jörn Möllenkamp.

Dauer: 90 Minuten.

Theatrical release in Germany: July 1, 2021

Termine im Summer-Special der Berlinale:

11. Juni 19.00 Uhr im Freiluftkino Museumsinsel

13. Juni 22.00 Uhr in der Freilichtbühne Weißensee

Aus Anlass der Publikums-Premiere am 11. Juni kann man via Live-Stream der Podiumsdiskussion ab 15.30 Uhr auf Twitter (@HEBerlinEuropa) und YouTube (@HEBerlinEuropa) folgen. Der Film wird außerdem am 1. Juli in den deutschen Kinos anlaufen.

Zitation

Natasha Klimenko, The Urgency of COURAGE. A film by Aliaksei Paluyan , in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/urgency-courage