Faruk and Mona, the main characters in "The White Fortress/Tabija", live in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The young protagonists fall in love with each other and the audience gets a glimpse into their (different) lives and especially into what keeps them busy: How they deal with the hopelessness that prevails in the country, even more so after the post-Cold War period. We spoke to the film's Bosnian-Canadian director, Igor Drljača, who was part of the first generation of mass exodus that began during the Bosnian civil war and who wanted to create the film to focus on the struggles of the younger generation in Bosnia.

zeitgeschichte|online: Why is the movie called Tabija, has the word a special meaning?

Igor Drljača: The word doesn’t have a special meaning, but the Bijela Tabija (The White Fortress) is one of the most recognizable medieval structures in Sarajevo since it overlooks the city. I wanted to bring some of the city’s history into the film, the history that is always in the background, serving as a reminder that this space has not healed. The problems of political corruption and nationalism, combined with poverty, are always there.

zeitgeschichte|online: Faruk and Mona, the two young protagonists who are representing different socioeconomic backgrounds, get to meet, a short window of possibilities to overwind boundaries opens. They grew up in different realities but understand each other. The story is backed up by fairytale and mystery elements. As the two stroll down the lonely street for example, the situation reminds Mona of a fairy tale, while Faruk thinks of the beginning of a horror movie. This contrast between horror and fairy tale is also taken up visually by the cinematic design and typical fairytale iconography. Why does the fairytale elements contest the horror ones in the end?

Igor Drljača: I wouldn’t say that fairytale elements contest horror ones. Fairy tales are very much rooted in in a reality defined by horror. Like in other fairytales, our protagonist finds coping mechanisms to deal with his seemingly hopeless situation. How one finds love in a post-war space like this is something I was interested in exploring, a space in which a future seems difficult and out of reach for many. When Faruk disappears, his disappearance is a matter of perspective. Mona’s perspective is the romantic one, but a far more insidious and real one is there throughout the film.

zeitgeschichte|online: What is the importance of the dog in the narrative development of the plot?

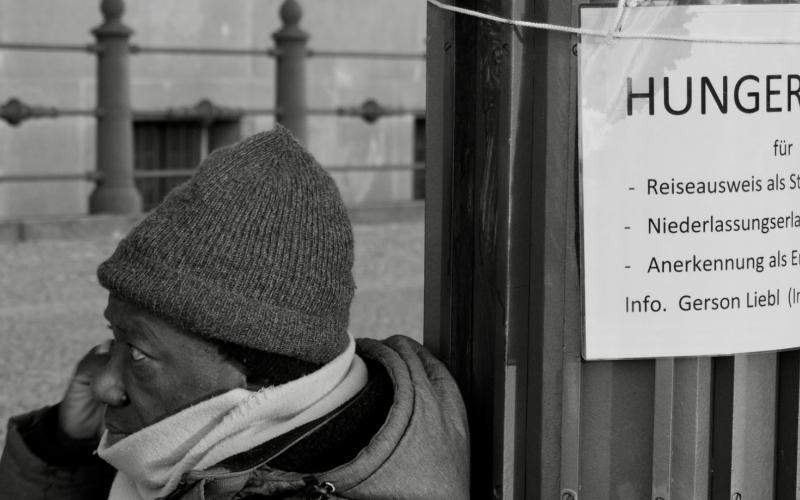

Igor Drljača: The dog is both real and metaphysical. It’s an omen throughout the film, and while it doesn’t move the plot, it is suggestive of trouble ahead if one pursues a particular path. I wanted the metaphysical elements in the film to serve as a source of tension. This tension comes from many different sources, whether it be the city’s collective trauma or the individual traumas of the post-war generation. There is also an inherent tension created by poverty, and the aimlessness that it causes, a type of boredom that leads to self-harm and which the new generation is increasingly trapped in. There is a massive 40%+ unemployment rate among young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that alone is enough for many to turn to other outlets to either make money or to simply just pass time.

zeitgeschichte|online: Did you have a specific audience in mind, creating "The White Fortress/Tabija"?

Igor Drljača: I was primarily thinking about the young people in Bosnia. Their future is uncertain, and many are leaving the country to look for opportunities elsewhere. There aren’t many films or even television shows made in Bosnia. They primarily import their entertainment, and given this fact, the problems of the people in Bosnia become invisible. The frustrations of the country’s youth seem more existential than real, and I wanted to make something that at least brings some focus to their struggles.

zeitgeschichte|online: As you already mentioned, the movie makes clear that there are few opportunities in Bosnia, especially for the young generation. At few points the protagonists talk about a (brighter) future. Is Tabija capturing the sentiments of the young generation in Bosnia right now?

Igor Drljača: My primary reason for making the film is to document and give form to a sense of hopelessness and inertia that exists in Bosnia today. When you see so many people leaving Sarajevo – and Bosnia at large – it is heartbreaking that some of the country’s most talented are taking their abilities elsewhere. They are moving their stories elsewhere, and are taking with them a part of what made Bosnia such a thriving creative space in the second half of the 20th century. I was in the first generation of this mass exodus that began during the Bosnian civil war. But what is more concerning now is this “cold war” post-1995 period, in which the country has not made concrete steps toward a future that provides for its people, and ethnic rivalrly is constantly used as a wedge issue.

zeitgeschichte|online: What attribution to Faruk’s character does the subtle excerpts of film footage with Nazi references, such as the loud artillery fire or the conversation between two Nazis in Sarajevo in a WW2 Propaganda movie? Why is Faruk the only one in Tabija visually confronting himself with this past? Is everyone in Bosnia effected in the same way by the consequences of war from World War 1 until the Bosnian war?

Igor Drljača: The people of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the region at large, including myself, carry inter-generational traumas that tend to be largely ignored, and Faruk is trying to break that trend. Bosnians haven’t really confronted the legacy of the wars waged in the 20th century, in part due to internal and external pressures that deny certain realities and responsibilities. There was no winner in this latest war. The Dayton Accords that ended the war were meant to provide a temporary framework, but remain in place. Dayton is a poorly constructed peace treaty that incentivizes political paralysis, continued nationalism, and rewards the type politics that were responsible for the war in the first place. The international community has in essence given up on Bosnia, and has given Belgrade and Zagreb the keys to preventing or starting another bloodbath. Because Dayton entrenches ethnic identities, politicians of all there ethnic groups continue to play a game that allows for ethnic rivalry to be the dominant discourse. As long as Belgrade and Zagreb are playing this game, and as long as the EU and the US are reluctant to step in (since they helped create the peace treaty in the first place), there will be no meaningful movement forward. This paralysis benefits the Croatian and Serbian political elites as much as Bosniak ones in Bosnia. At the same time, while some of the criminals who were the primary perpetrators of the various wars in the region have been tried, their legacy lives on, and is even celebrated by many in some parts of the country.

zeitgeschichte|online: Other subtle elements in the film are the political themes. Viewers of the film can observe an election campaign in the background, and it seems that both Faruk and Mona, including their surroundings, act outside the political framework. What kind of political atmosphere did you want to portray?

Igor Drljača: Elections in Bosnia are always anxiety inducing, but the act of voting doesn’t provide an outlet for change or a meaningful dialog for younger generations. Politicians who might want to change something lack a framework for enacting those changes. Politics becomes almost purely performative in the Bosnian context. Career Politicians in the country are increasingly disconnected from reality, and have forgotten or at best have little concern for most of its people.

zeitgeschichte|online: "The White Fortress/Tabija" seems like a way out of the valley's misery. Would you say that for the inhabitants of the golden valley the white fortress remains out of reach?

Igor Drljača: Yes, in a manner of speaking. The White Fortress is a reminder of how the country remains trapped. But the film is also a reminder that traveling to an idealized version or period of the city’s history is not a realistic way of dealing with the traumas that we all carry with us. We come up with elaborate ways to convince ourselves that things have been better, and therefore will be better again. But this is not real. For me, I think this film was also about exploring my own rootlessness. I am no longer a part of the daily life of that city and as more of us leave, more of us feel like strangers in Sarajevo, very much like travelers from another time.

"Tabija/ The White Fortress" läuft am 20. Juni 2021 um 17.30 im Rahmen des Berlinale Summer Specials auf der Neuen Bühne Hasenheide.

Zitation

Alina Müller, Vanessa Prattes, „Their future is uncertain“. Interview with director Igor Drljača about Bosnia's young generation in "The White Fortress/Tabija", in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/interview/their-future-uncertain