On 12 October 1909, the government doctor Friedrich Karl Georg Liebl[1] appeared in front of the assessor of the Imperial District Office, Dr. Asmus, in Lomé, Togo, in order to financially settle the future of his unborn child. In his statement, he noted that he had “lived together” with the “native Kokoè Aite Ayaron” during the last years of his stay in Togo which at the time had been a so-called German Schutzgebiet for more than two decades. Liebl further reported that “the Kokoe” was expecting a child due in January 1910, and that for raising this child he would store 1000M in her name, of which she was allowed to withdraw smaller amounts in a precisely defined frequency within two years—that is, if the baby would turn out to be a “Mulattenkind”. If it were to be a Black child, Liebl stated, she would only be entitled to 200M after the birth, the rest was then to be sent back to him. At the time of this statement, Kokoè was supposedly staying with her brother Emanuel, who was a nurse, so she could spend her pregnancy in his care and eventually have the child there as well.[2]

In February 1910, said brother, Emanuel Ajavon[3], appeared to confirm that his sister had given birth to a child of mixed race on 26 January, which would later bear the name Jean Johann Liebl. The respective report filed by a secretary of the Imperial District Office shows that Emanuel Ajavon was consequently given 50M for expenses related to the birth plus 10M of alimonies each for the months of January and February, as had been laid out by Fritz Liebl in advance. Moreover, two small notes—the last one dated 31 March of the same year—read that on the first account another 70 and on the second “100M have been paid to Kokoè”[4].

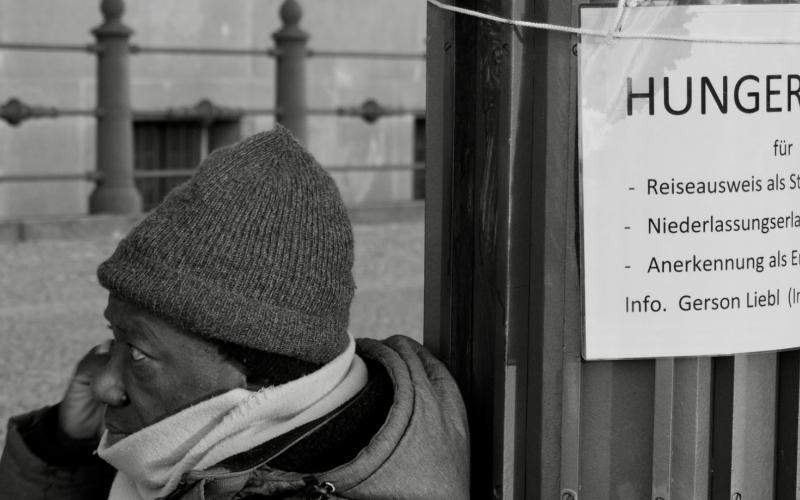

Sources like these are read out in Moritz Siebert’s documentary “Zahlvaterschaft” by an off voice, while the audience is shown images of a man camping in front of the Berlin Town Hall, demanding travel documents, a residence visa, and the recognition as the grandchild of German government doctor Fritz Liebl.

The hunger strike of the stateless Gerson Liebl in November 2019 marked the climax of almost 30 years of citizenship activism. In 1991, the trained goldsmith moved from Togo to the German Bundesland Rheinland-Pfalz and directly applied for asylum as well as for German citizenship on the basis of being the grandchild of a German—which were both rejected later on. Liebl claimed that his grandparents Edith Kokoè Ajavon and Fritz Liebl were in fact married and eventually provided documents to prove it[5]: The ceremony was held according to Indigenous traditions around Aného, Togo, by chieftain Kwakou Kponton in 1908, and at the time represented the only form of marriage possible to the couple since Colonial Law forbade Mischehen. But the German state neither recognized the marriage then—since when taking place, it was not legally valid under German law (unlike Fritz Liebl’s second marriage to a German woman and on German ground a few years thereafter) —nor does it do so now, which then and again served as one of the main arguments against Liebl’s various attempts at naturalisation as a national. Based on the German Law on Citizenship of 1913[6], different German courts ruled against Gerson Liebl over the years, claiming that in German colonial times legal lineages were only formed by marriage and legitimate children and that therefore, he was Togolese and not German. All the while, the Togolese state actually deprived him of his papers claiming the exact opposite, namely that he lived in Germany and was (of) German (heritage), which in the end made him a stateless person—intergenerationally in between. Ironically, his brother Rodolf Dovi Liebl received a German passport in 1996 when filing for it in Lomé. However, it was withdrawn from him again a mere half a year later.[7]

In 2003, when Gerson Liebl petitioned for “Wiedergutmachung staatsangehörigkeitsrechtlichen Unrechts“ in the colonial times of the German Reich, the official refusal read that the Federal Republic of Germany was “aware of its colonial past” since the German Minister of Foreign Affairs had condemned colonialism as a crime against humanity and apologised for it on behalf of the country at the World Conference against Racism two years prior to the petition.[8]

Shortly after moving from Straubing, his grandfather’s hometown, to Berlin in 2009, Liebl was detained—which had happened before—and deported to Togo after 18 years of living in Germany, leaving behind his wife and child. Only in 2017, after his son became a German citizen, was he allowed to return to the country due to family reunification. Not giving up on his demands, he went on hunger strike—one form of protest he had not yet turned to, but which would also prove itself to be mostly powerless against the German state’s determination to deny his claims. Although immigration authorities offered him a temporary leave to remain after he had been taken to the hospital on the tenth day of his strike, the City’s House of Representatives held on to prior decisions and commented that even if the Federal State were to adopt a reform concerning German descendants from former colonies, it would not include Gerson Liebl “because the form of acknowledgement of paternity described by the petitioner was regarded as a so-called Zahlvaterschaft until 30 June 1970, which did not result in any kinship relations”[9].

All in all, Gerson Liebl faced a great many resolutions and denials by the German state (and, in fact, the Togolese state as well) over the years, which were often contradictory and characterised by the concurrent dissociation and perseverance of (past) colonial realities.

“We are Germans, we are white, and we want to remain white”[10]

Around the time of his father’s, Jean Johann Liebl’s birth, shortly before the Law on Citizenship was passed, a public debate about Mischehen as well as Mulattenkinder took place amongst German political decision makers which began within Colonial territories and eventually reached Berlin.[11] While the participants of the debate generally agreed that a legal reform itself was necessary since there were next to no detailed regulations, most—who were either employed in the colonies or by the Reichskolonialamt—strongly opposed the (re-)legalisation of marriages between Togolese women and German men, which were forbidden at that point, on the base of racial arguments. According to Adolf Friedrich Duke of Mecklenburg, who resumed office as Colonial Governor in Togo in 1912, and his staff, allowing so called Mischehen would have endangered “das scharfe Rassengefühl, welches wir unbedingt brauchen”[12]. Next to his ostensible concerns about protecting the “status of white women” and the inseparability of marriage—which, according to him, could not be guaranteed in these cases due to “climatic reasons”—he was mainly driven by Social-Darwinist and white-supremacist thought which he summed up under a “wissenspolitische[r] Standpunkt”[13]. Dr. Asmus, the assessor of the Imperial District Office in Lomé who was not only in charge of the guardianship for Jean Johann Liebl but dozens of children of Togolese mothers and German fathers, furthermore emphasized the crucial importance of the ban on carrying your father’s surname. He imagined that in a future without this ban it would at some point become severely difficult to tell “African” and “European” individuals apart. Asmus believed that descendance was mainly determined by the family name—especially once racial lines started to blur—and could therefore with all that it entailed be (legally) claimed by people who, in his world view, were not entitled to it. So, in order to prevent children like Jean Johann Liebl and their descendants from ever potentially becoming German and including themselves into the society of their colonisers, he proposed a Regulation in 1909 which ensured that the children in question were named after their mothers—or in fact, after their parents of colour.[14]

While certainly being an act of political rebellion against this racist and misanthropic world view, the illegal bearing (and later also the subsequent passing on) of Jean Johann Liebl’s paternal name initially lost its immediate relevance in 1914, just like the entire debate around family politics in Togo, when World War I started, the colony was rapidly seized by British troops, and a new colonial governance began.

German Citizenship: Designed to exclude

Let us look back for an instant and attempt to summarize the legal history of German Citizenship (very briefly).

During the German national movement of the 19th century, nationality as an institution, namely the development of a procedure for obtaining an early form of citizenship and therefore being part of the nation, provoked existential debates around belonging and foreignness. The importance of a differentiation between one nation(ality) and the other grew and hence appeared to call for further definitions. Those with agency within the movement believed that a cultural and ethnic “entirety of Germans” categorically existed, which for example included Austria.[15] In 1871, German nationality became thereupon a concrete instrument of inclusion and exclusion. While it was used as the core element in integrating inhabitants of the newly annexed Alsace-Lorraine on the one hand, it simultaneously manifested the severe sentiments against and rejection of Poles and above all Jews on state territory on the other.[16] As the procedure established its bureaucratic character and people became components of meticulous statistics, factually discriminated social groups were formalised—which were then either fully excluded from attaining citizenship or had to prove their assimilation through various special regulations.[17] The so-called Abwehr der Polen helped to significantly increase the sense of belonging within the mainstream society and can be seen as one of the decisive starting points of fundamentally defining who is in by who is out. Through the Initiative of 1894/5 it became harder for foreigners to become German while (those perceived as) Germans living abroad, e.g., Wolgadeutsche, had an easier time getting or retaining their citizenships.

In 1913, when the Law on Citizenship was passed, descendance became the sole pillar of German nationality, making it a ius sanguinis (of the blood) and not a ius soli (of the soil). Therefore, the racial unity which had been called for by white decision makers for decades legally manifested itself and the (always executed) separation between biopolitics in the colonial metropolis and biopolitics in the colonies was officially enshrined.[18]

Even though both British and French law differed from the German version and was partly territorial (ius soli) equal citizenship rights for colonised subjects were neither reached nor ever even pursued in their pre-World War I territories either. As Dominik Nagl aggregates, “the principle of a discriminatory bipolar colonial jurisdiction and the exclusion of the colonial subject from the legal community of citizens characterises modern colonialism overall”[19]. Separate legal, political, and economic systems were crucial in creating and maintaining asymmetrical colonial governance. Thus, keeping colonial subjects from obtaining German citizenship with the privileges and duties it entailed was important for two reasons: Firstly, to remain able to exploit Colonial territories and people, and secondly, to successfully evocate a national community at home based on pseudo-scientific, racist, anti-Semitic, and xenophobic concepts amidst stirred European competition. However, the crucial difference between Germany and its European neighbours is not only the early loss of its colonies through World War I but also the fact that the 1913 Law on Citizenship[20] still exists today.

But let us proceed chronologically: The small number of individuals from African, Asian, and Pacific overseas territories who (temporarily) lived in Germany during colonial times were mostly either male children of noble families who were sent there to study or (forced) participants of the racist-exotistic spectacles known as Völkerschauen. Their legal status was not comparable to other migrants or tourists, they did not get proper visas and were forced to rely entirely on security by colonial officials, missionaries, or employers. When they or their descendants married white women after World War I, these women would lose their German citizenship (which corresponds with the rules of many European countries at the time).[21]

Despite evidential racial discrimination in Europe, however, there was never a Rasserecht established anywhere on the continent until the Third Reich. Within twelve years in power, the Nazis built a large system of racially discriminatory citizenship regulations[22] which were abolished again by the Allied occupation after World War II. Almost the entire pre-1933 judiciary was re-introduced in this context, which as a concept was distinctly “provisory and retrograde”[23] and included the 1913 Law on German Citizenship. As the rest of the 1949 Grundgesetz, the incorporation of the Law on Citizenship was contradictory in its endeavour to simply re-adopt pre-1933 regulations on one hand and not only revoke but attempt to balance out Nazi regulations and their horrid consequences on the other. The former colonies, which never went through a process of decolonisation but were lost to other Empires during World War I already, were excluded from any reflections in the process and made fully invisible in the context of nationality and post-national socialist Germanness.

In the following, the emerging idea that Germany, unlike most of its European neighbours, was no country of immigration was “meant rather prescriptively than descriptively”[24], as Jean-Pierre Félix-Eyoum and Florian Wagner point out. The Federal German government was determined not to grant those considering moving abroad from former overseas territories a so-called Kolonialbonus. Furthermore, no efforts were ever made to explicitly recruit people from these countries as Gastarbeiter*innen—as done in England with the invitation to the Windrush-Generation between 1948 and 1971 (which of course later resulted in its own scandal around citizenship). Neither was a statistic category for immigrants from former colonies established, whether descendent of German citizens or not. Up to this point, they hardly play any part in reference books about migration and/or legal history in Germany.

In the 1990s, alongside Gerson Liebl half a million Togolese citizens fled from Togo’s repressive regime, but due to the asylum regulations of 1993 they very rarely received asylum in Germany, despite the shared history of the two countries. At the same time (as well as during the decades before already), some individuals from former German overseas territories were able to become German citizens unsystematically or in summary proceedings, due to economic necessities. Félix-Eyoum himself, for instance, is from Cameroon originally and became a German citizen in 1980 since he was a trained special education teacher, and members of this professional group were needed in Bavaria at the time.[25]

In 1999, Jürgen Habermas wrote that normative terms alone cannot explain the entity of a legal national community and that the juristic construct of the constitutional state therefore leaves a hole which triggers its filling with a “naturalistische[m] Begriff des Volkes”[26]. One year after these lines were published, the Social Democratic-Green coalition of the German government issued the first and, as of now, only reform of what was at that point the almost one hundred-year-old law still called the Reichs- und Staatsangehörigkeitsgesetz.[27] Once again, the reform provided no regulations for people from areas that had been under German colonial rule at some point. In general, it did adopt territorial elements (ius soli) and was overall supposed to simplify the (second and third generation) migration to Germany. Nevertheless, it was and is often criticised for not effectively reaching that goal in practice.[28] Effectively, it did not pick up on claims like Gerson Liebl’s in any way. Citizenship, which in itself remains an infinite negotiation process—based on various categories which again need their own negotiation processes—in the German case continues to be first and foremost exclusive, oblivious of historic Global entanglements, and shaped—or rather actively not shaped for most of the time—by white mainstream actors only. Instead of igniting an extensive revision of nationalist-socialist thought and its roots, the German Federal Republic’s preferred handling of its legal history can only be labelled forgetful at best and a deliberately negligent continuation of racial hatred at worst.

In summary, until 2000 those with legal and political agency felt no immediate pressure to reform the Law on Citizenship, which still existed in its form from 1913. In fact, it continued to reflect the mainstream ideas of how nationality was formed and formed itself: based on the exclusion of othered individuals and simultaneously stimulating the remembrance of a pre-1933 national unity which was not yet tied to nationalist-socialist atrocities. And even as the 2000 reform was eventually passed, it did not fundamentally change those elements. Although a territorial legislation was put in place, which for the first time would allow people to become citizens if they were born in the country and met certain requirements, descendance remained the main pillar of the German Law on Citizenship—for some, that is. Gerson Liebl, whose second generation descendance from the German colonial doctor Fritz Liebl can be proven, as we have established when retracing his case alongside the source material, remains excluded from the ius sanguinis. For almost thirty years now, authorities have told him that the two major legal obstacles in his pursuit of German citizenship were firstly, that his grandparents were not married and secondly, that Fritz Liebl was only the Zahlvater of Jean Johann Liebl, which did not establish paternity. In 2000, the legal administration failed to tackle any of these complications in its reform and thereby revise its colonial past. After all, the Law on Citizenship was established when Germany was a colonial power. It was passed in a time when marriage under Colonial Law was illegal for Fritz Liebl and Edit Kokoè Ajavon and when raising a mixed child was thereby rendered impossible.

The handling of Liebl’s case and the circumstances he has been forced to live under for several decades now are part of a colonial continuity which is kept in place by a defensive, complicit, and comparative silence[29]. This active version of collective forgetting is defensive of as well as complicit with its national collective which has been the offender of colonial trauma. Constitutively, the silence legitimizes itself through comparative strategies which are designed to make concrete legal reparations impossible, play off victims against each other and thereby decrease the importance of colonial (and non-white) memory even further. Though this silence has been long-term, it is also limited and will be forced to loosen up and/or at least transform. The national collective it has been nourished by and protective of, has started to be challenged and entangled in a postcolonial negotiation process.

Although largely kept remote from civil power so far, actors like Gerson Liebl have developed agency, shaped their own fates, and shaped German history and nationality regardless. Moritz Siebert’s short filmic portrait accompanies and documents this in a cautious yet unequivocal way. The colonial silence around the protagonist is continuously performed by the various pedestrians who are shown passing by his struggle. It cynically culminates when one of them offers Liebl, who sits right next to his sign declaring “Hungerstreik”, their leftover food. Additionally, the urban black-and-white imagery creates timelessness and deprives the audience of a feeling for nature, seasons, and temperatures. While the small human (non-)interactions happen on-screen, the off voice continuously reads out historic sources as well as current legal documents. This filmic handling of written source material which gets only commented on or contextualised through the film’s (symbolic) images offers an interesting perspective to every contemporary historian. In only twenty-two minutes the film is thus able to transfer a large amount of what has been carved out in this article to its viewers.

Zahlvaterschaft (Deutschland 2021)

Regie und Produktion: Moritz Siebert, Drehbuch: Hanna Keller und Moritz Siebert.

Dauer: 22 Minuten.

Termine im Summer-Special der Berlinale:

13. Juni 21:30 Uhr im Open Air Kino HKW

[1] Referred to as Fritz Liebl, which he was often called, in the following.

[2] See Statement Dr. Liebl, “Fürsorge für uneheliche Mulattenkinder deutscher Väter 1905-1914“, Lomé, 12.10.1910, German Federal Archive Berlin R150/1170. Quotes are taken from pages 1 and 2.

[3] In the source material, both Kokoè’s and Emanuel’s names are spelt differently at times. I have used and will use the spelling which Gerson Liebl uses in his statements, unless it is part of a direct quote.

[4] See Statement Kokoè’s brother, “Fürsorge für uneheliche Mulattenkinder deutscher Väter 1905-1914“, Lomé, 12.10.1910, German Federal Archive Berlin R150/1170: 1.

[5] „Bescheinigung der traditionellen Eheschließung zwischen Friedrich Karl Georg Liebl und Edith Kokoè Ajavon, ausgestellt vom Stammesfürsten Nana Quam-Dessou XIV der Stadt Aného/Togo am 23.04.1997“, private collection of Gerson Liebl.

[6] The law of 1913 still is the base of today’s law, which the article will elaborate further in the next subchapter.

[7] About the entire paragraph and for a detailed account, see interviews with and articles about Gerson Liebl, e.g. Bernhard Hübner im Interview mit Eckart Dietzfelbinger, „Das ist rassistisch“, taz, 20.2.2009; Susanne Mermarnia, Gerson Liebl’s letzter Trumpf, 7.5.2021; Schatten der Kolonialzeit, DW, 28.11.2019; Gerson Liebl’s Website [all last downloaded 13 June 2021]; furthermore: Concluding Statement of the Petitions Committee. Berlin House of Representatives (2019).

[8] Concluding Statement of the Petitions Committee. German Parliament (19.6.2003): 24.

[9] Concluding Statement of the Petitions Committee. Berlin House of Representatives (2019): 5-6.

[10] Speach Dr. Heinrich Solf, Reichstag Protocols, Meeting 53, Berlin (2.5.1912).

[11] See Speach Dr. Heinrich Solf; „Mischlings- und Mischehenfrage. Diskussion eines Verordnungsentwurfs durch den Gouvernementsrat (Sitzungsniederschrift vom 18. Sept. 1912)“, German Federal Archive Berlin R150/412; Rapport de Dr. Asmus sur le port de noms allemands par les enfants métis. Archives Nationales du Togo (ANT) - FA3/185: 143-147.

[12] Mischlings- und Mischehenfrage: 2-3.

[13] Ibid (all citations).

[14] See Rapport de Dr. Asmus sur le port de noms allemands par les enfants métis. Archives Nationales du Togo (ANT) - FA3/185: 143-147.

[15] Dieter Gosewinkel, Einbürgern und Ausschließen. Staatsangehörigkeit und Bürgerrecht in Deutschland während des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Germanistische Abteilung 137, no. 1 (2020): 373.

[16] See ibid. 376-7.

[17] For detailed information and numbers see Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Bd. III: 1849–1914, München: Ch.H. Beck Verlag, 1995: 961-65.

[18] See Julia Angster, Staatsbürgerschaft und die Nationalisierung von Staat und Gesellschaft. Staatsbürgerschaft Im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Dieter Gosewinkel and Christoph Gusy, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck Verlag, 2019: 125-44.

[19] Dominik Nagl, Unterordnung und Trennung. Die rechtliche Stellung von Europäern und Indigenen in den europäischen Kolonialreichen, Fremd und rechtlos? Zugehörigkeitsrechte Fremder von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Ein Handbuch, edited by Altay Coskun and Lutz Raphael, Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 2014: 292.

[20] German Law on Citizenship, The current version of March 2021 [last downloaded 13 June 2021].

[21] See Jean-Pierre Félix-Eyoum and Florian Wagner, Das verdrängte Politikum. (Post-)Koloniale Migration nach Deutschland, Zeitgeschichte-online, Februar 2021 [last downloaded 13 June 2021].

[22] It would extend the framework of this article to further describe these regulations. Since the focus is set both on the Colonial and the reunified period of Germany (when Gerson Liebl migrated), the time in between can only be touched upon superficially when immediately relevant. Also, I will not be able to discuss regulations in the GDR since they did not prevail within German law after the fall of the Berlin wall and are therefore not directly linked to our case.

[23] Gosewinkel, Einbürgern und Ausschließen: 385.

[24] Félix-Eyoum and Wagner, Das verdrängte Politikum.

[25] See ibid.

[26] Jürgen Habermas, Der europäische Nationalstaat – Zur Vergangenheit und Zukunft von Souveränität und Staatsbürgerschaft, Die Einbeziehung des Anderen. Studien zur politischen Theorie. Edited by Himself. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1999: 139-40.

[27] German Law on Citizenship, The current version of March 2021.

[28] See Henning Storz and Bernhard Wilmes, Die Reform des Staatsangehörigkeitsrechts und das neue Einbürgerungsrecht, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 15.5.2007 [last downloaded 13 June 2021].

[29] Concurrent to a passive colonial remembrance, in which artifacts and relics have been gathered in the collective archive but never made it to the canon, there is an active form of forgetting at work: the silence. When silent, a topic is banned from the collective communication without being deleted. Therefore, what is silenced is simultaneously conserved in a state of latency without being processed in any way. Longer-term silence is never random or clumsy but follows certain patterns in which stories and memories remain unheard as long as there is no memory frame—which the collective would have to cultivate—in place for them. Generally, such a defensive and complicit silence protects offenders in the event of a trauma. Not only are they not being prosecuted in any way, but they mostly do not pass on their trauma intergenerationally, which victims do. But even later generations of victims are not able to claim their rights, be medialised and therefore heard doing so if a silence in the name of the offenders and the mainstream society (both of which overlap in the German case) continues. See Aleida Assmann, Formen des Vergessens. Historische Geisteswissenschaften Vol. 9. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2016; Paul Connerton, Seven Types of Forgetting, Memory studies 1, no. 1 (2008): 59-71.

Zitation

Sophie Genske, “Zahlvaterschaft”. A Brief History of Gerson Liebl’s Case, the German Law on Citizenship, and Colonial Forgetting, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/zahlvaterschaft