In some of the NS concentration camps, inmates were able to take clandestine pictures from the spring of 1943 until the autumn of 1944. Although they were risking their lives by doing so, prisoners in concentration and extermination camps took photographs and even managed to smuggle canisters of film beyond the camp gates. Yet their hopes of galvanising the Global public into action would remain unfulfilled. In the vestiges of the camps, French director Christophe Cognet retraces the footsteps of these courageous men and women in a quest to unearth the circumstances and the stories behind their photographs, composing as such an archeology of images as acts of defiance.

zeitgeschichte|online: Working as a director of documentary films you have spent many years studying the Shoah, NS concentrations and extermination camps and the biographies of the victims and the survivors. You have already devoted three films to these subjects: L'atelier de Boris (The Boris’ Studio, 2004), Quand nos yeux sont fermés (When our eyes are closed, 2008), and Parce que j'étais peintre (Because I was a painter, 2013). Your book Éclats, published by Editions du Seuil in 2019, also is written on the same subject as well. What was your motivation to continue your work on the subject in À pas aveugles (From where there stood)?

Christophe Cognet: After Because I was a painter, I thought I had completed my work on this subject, in the form of travel. But something in me resisted this feeling: taking my research, I had already come across most of the clandestine photos that are in From Where They Stood, choosing not to include them, because that would have made the film too imprecise. And one day I discovered Leib Rochmann's book, «with blind steps across the world», and thinking about this very beautiful title, something resonated in me: I told myself that the drawings were above all a question of gaze and less body, while for the photographs it is the opposite. You don't have to be physically in front of the subject of your drawing to do this. In a concentration camp, you can watch an execution for example and draw the corresponding picture from memory in the evening in a block. On the other hand, to take a photo, you have to be there physically in front of the subject, but not necessarily aiming in the camera or even looking at what you are photographing. It was the case of pictures of George Angeli to Buchenwald and certainly a part of those of Alberto Errera Birkenau. This simple realization made me want to make this film: a body that moves in a place, a question about the look and the images, these are questions of cinema: this film is more physical and harsher than the previous, which was more "mental" (in the sense of the “cosa mentale"). And the Book Éclats comes from the film project: an editor (one of the most important in France), Le Seuil, found out that I was preparing a film on this topic, he read the first draft of the film project and offered to write the book, which was therefore written during the entire preparation period of the film.

zeitgeschichte|online: No film has ever dealt head-on with the clandestine photographs taken in the Nazi camps. What was your inspiration to make this film on clandestine photographs?

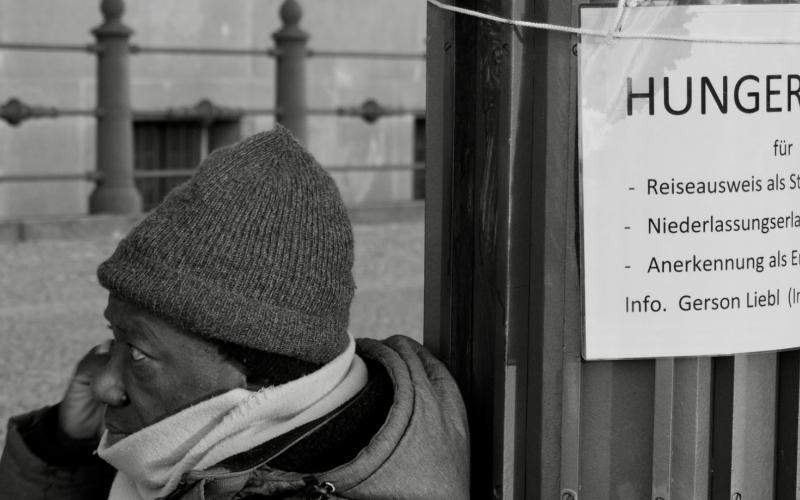

Cognet: We have seen the photographs and the films shot by the Allies upon their discovery of the camps, that’s how we visualized the camps and the Shoah. But what about the images that were captured by the deportees themselves? The need to represent the camps from the inside, by the very victims of the Nazi system, is absolutely essential. It’s about the spirit of resistance (in every sense of the word), but also the need to bear witness to the mistreatment, the appalling living conditions, the torture, and the assassinations that occurred in those camps. It’s about countering the images of concentration camps as controlled by the SS, and addressing the very essence of the death camps, which were designed to be concealed from the outside world and to prevent any representation of what occurred inside. These images are essential because they’re the only ones that share a common experience— the photographers and the subjects of these photographs, all being in the camps together. This sense of equality is a determining factor in both the status and the very nature of these images—something the photographs, films, and drawings made by the Allies upon their discovery of the camps simply cannot achieve—the common fate that binds the one taking the picture and the one who appears in the photograph.

zeitgeschichte|online: How did the work of your former films on survivors of NS concentration camps influence the production of À pas aveugles?

Cognet: For me, it is the extension of the same path, that of the exploration of the images made by prisoners from inside the camps. In my spirit, this last film and the previous one form a kind of diptych. In all this work, I am guided by the memory of the survivors that I have met during these years.

zeitgeschichte|online: The film begins with a message “We must look at these pictures”. What is the idea behind this commanding statement?

Cognet: Simply because these men and women risked their very lives to produce these images for us! We must look at these pictures—be ready to receive them—without any dogma and without prejudging the effect they will have on us, or what they’re about to show us.

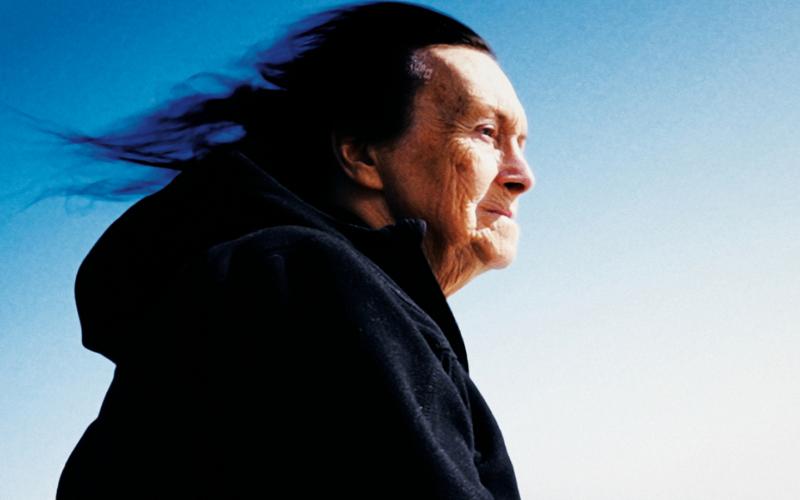

zeitgeschichte|online: For the production of your former films you were able to interview living witnesses, people who experienced the horrors of the concentration camps themselves. Now, as the number of survivors is declining, which potential do you see in photographs as a testifying medium and medium of memory?

Cognet: I do not believe that the images can bring us knowledge or reliable testimony on the facts. The images can be a support to provoke or initiate a testimony, but not replace it. These photographs are therefore as much the testimonies of what we see there as of the extreme conditions of their shots. Because what they designate is very difficult to understand. I am not looking for new knowledge about the camps or the Shoah in itself.

It is the opposite: It is thanks to the knowledge accumulated on these events that we can now look at these photos, and try to understand them, at least in part. With this work of exploring images—I insist, it's a long road of exploration—in a fleeting and labile way, maybe we can have a vision, a pure perception of what those amps were. It is sensitive, not intellectual, knowledge that is very valuable.

zeitgeschichte|online: For your work on your earlier films you have talked to Georges Angéli (1920-2010), a French survivor of Nazi concentration camp Buchenwald. He is one of the brave prisoners who took seven pictures of “the everyday life” in the concentration camp and one of your protagonists in À pas aveugles. Have you recorded this conversations? Why did you not include some parts or scenes of your conversation in the film?

Cognet: I had actually recorded part of our discussions - but only part of it, and on a fairly rudimentary device. In the preparation work, I chose not to insert in the film, for reasons of coherence of the enunciation and of the narration. Also because, to be honest, when I saw him, Georges had a hard time talking about what he had been through: he was an extremely sensitive man, who often spoke with tears in his eyes, and who lost in his memories. It made what he said hard to follow. But the most important thing is that integrating interviews in this film was not coherent with its research, its direction. I told myself at one point that these interviews could have "guided" us on the spot, in the remains of the Buchenwald camp, but it did not work. It would have been necessary that Georges was still alive and that together we explored the sites to seek the path he had followed in the past. That would have been great. But unfortunately, no photographer or person who took part in the shots was still alive at the time of filming.

zeitgeschichte|online: You are a director working with moving images. How did you transform the photographs—still images, capturing a unique moment in history—into moving images in the film? Which similarities and which differences do you see in the two mediums which have the ability to make the past present again?

Cognet: The photographic process forms an image by taking an imprint of the world it represents. Therefore, photographs are a physical, material trace of what was. At the same time, they’re an opportunity to present again to our eyes the people and places that were photographed. It has often been noted that photography, like cinema, records (in the words of Jean Cocteau) "death at work". We forget that photographs are also the opportunity to revive—to "make present" again—the beings who are recorded there, even as ghosts and apparitions.

Cinema and photography are always the material trace (in any case with the film process) of an encounter between the one who makes the image and what is reprinted - character or landscape. The difference obviously stems from time: the photograph is a shine, the cinema records a block of duration. My work in this film was partly to try to replace the clandestine images in the sites and to tell this research: time, the story of this research is cinema.

zeitgeschichte|online: You saw the production of À pas aveugles as a quest tracing back the historic capturing of the photographs. The intention was to find the original framing of each photograph. In present day, you went to the memorials of the concentration or extermination camps trying to find the capturing frame of the photographs. For your search you used glass tops with the original negatives on them like maps. Why did you choose this approach?

Cognet: I therefore wanted to consider photographs as much as acts as images. To understand them, I therefore had to try to understand their conditions of realization. Each time retrace the history of their manufacture. For that, it was necessary to go on the spot, in the sites where they had been made, among the remains of the camps. the story of the film thus parallels the history of this research with that of their realization. My goal is not necessarily to find the exact angle or the exact point of view of each photograph but to provoke questions in this double movement. And sometimes a time tremor is caused, in a fleeting and labile way, maybe we can have a vision, a pure perception of what those camps were. It is sensitive, not intellectual, knowledge that is very valuable.

zeitgeschichte|online: In the film you put the glass tops with the original negatives like a unique piece of a puzzle back to its original place where the photograph was taken. In these moments the screen is showing multiple time layers or dimensions. In front you see the past scene of the glass tops negative depicting the NS concentration camp and through the glass top in the background you see the memorial and its visitors today. Are you creating a new form of visual memory with this approach? What should be the conclusion for the audience?

Cognet: I had acquired the conviction that it was necessary to look at them as they had been made: by walking. So I did all this at the same time, in the same movement, going back and forth a lot. It is therefore a progressive discovery. For me the film is a kind of journey which tells the story of an impossible encounter with the past, but which sometimes finds some real interstices of perception. An experience of adventure at a glance, sometimes blocked, often impossible. The photographs as a force of attestation when considered in their two dimensions: acts and images. Sensitive knowledge (and non-intellectual). The film for me is therefore above all a reflection on the images, on their shortcomings, their possibilities, their powers and their inaccuracies.

zeitgeschichte|online: À pas aveugles is an expert film. Not only did you interview historians like Tal Bruttmann or archivists like Albert Knoll but the film itself requires a lot of background knowledge. How did you research this film?

Cognet: There is the research that I have done for twenty years. This film and the research on which it is based, owes everything to the relationships I made with the deportees I met afterwards, including their families, and their children (many who are my parents’s age). They’re the ones who led me to visit the sites of the old camps and consult the funds dedicated to the collection and conservation of these images. They also allowed me to meet the curators and historians who work on these topics, in France, Germany, Israel, Poland, the Czech Republic, the USA, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy. These meetings, combined with documentary research, allowed me to determine how questions arise about images in times of war, the representation of camps, and the Shoah.

And in the book I tried to describe each of these images, which gave me a very deep attendance of these images before the shooting.

Combine the exploration of places where they were made with the search for words to describe them was a very intense experience, both knowing and realizing the immense difficulty that we have to understand them and our near impossibility to apprehend what were the camps and the Shoah. And what I saw in them, what I perceived, is the immensity of my ignorance and the gulf that separates us from the concentration camp experience: this perception is very precious, it is unique. And I am deeply convinced of this : only the work of cinema and writing can bring it to us.

zeitgeschichte|online: In the film you yourself play a character—you are seen in many scenes, asking questions, talking to the experts and walking around the grounds of the memorials. Your own depicting is a choice—which role do you play in your film?

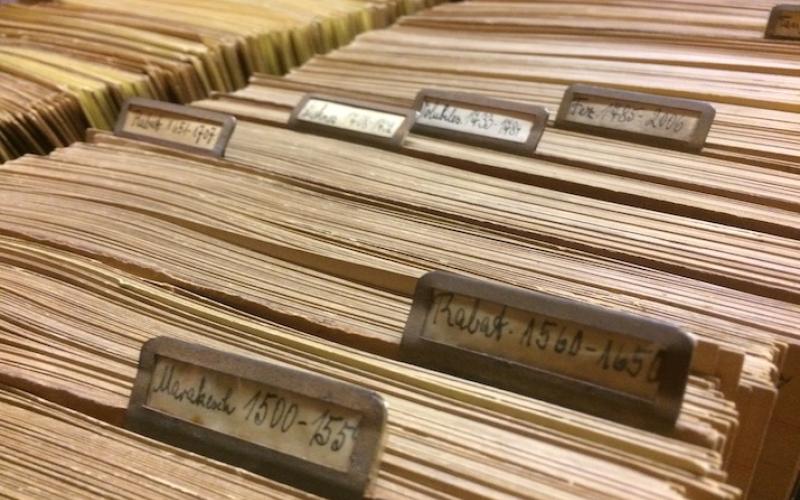

Cognet: I wanted the film to be on a human scale, fragile, centered on ongoing research and not on established knowledge. The simplest and most clear was that I play a "character" who, in the present day, leads a meditative and serious quest for these images and their power: the power of absolute disaster. Along the way, I reconstruct the stories of their authors, meet historians and curators, scrutinize the archives, and read and listen to the testimonies that remain, cross-checking them. I survey the remains of the old camps, try out real and imaginary compositions, and see if the various elements match... I reach out across abysses. Naturally, my part has to be as discreet and humble as possible: my “character” is only there to share the information he has gathered. But make no mistake: although I have spent many years studying these events, the emotion and the concerns that drive this project have not weakened—on the contrary.

zeitgeschichte|online: Who are the real protagonists of your film? The prisoners taking the photographs or the photographs itself?

Cognet: Both I think: by retracing their acts in all the risk taken, it is also a way of doing them justice, of paying them homage; to me the film is a kind of praise for them.

zeitgeschichte|online: One other group of characters is showing in the film: the tourists and visitors of the memorials today. Your former film Parce que j'étais peintre (2013) and À pas aveugles have similars scenes on the entrance to main camp (Stammlager), Auschwitz I. The scene in Parce que j'étais peintre is showing a female visitor taking pictures of the gate and its inscription “Arbeit macht frei” with her phone. À pas aveugles depicts a small group of visitors taking selfies and pictures from each other in the main alley of Auschwitz I. Why did you cut these scenes in the final cut of the film?

Cognet: In a film which questions the diffuclity in making images, it seemed important to me to show our contemporary practice of images, without judging it. Simply show the abysmal gap that exists between risking your life to take a photo, sometimes getting ready for months, and taking a camera or cell phone out of your pocket and taking a photo in seconds.

And then, it's important to situate the film now, in our time, nowadays, and nowadays, there are tourists and visitors in the remains of the camps who take photos and "selfies".

zeitgeschichte|online: The audiovisual representation of the extermination of European Jews by the National Socialists is discussed not only in history but also in film industry. In your film you decide to show the Images in Spite of All. How do you as a director reflect on heated debate and controversy about the visual respectively audiovisual representation of the Shoah?

Cognet: This is a very large and complex question - in my book I devote about 30 pages to it. We should go back to Rivette's article on Pontecorvo's film, and again before on the emotion of the expression "a tracking shot is a moral affair"... And even to the study of the prohibition of images in the Ten commands, through Adorno's reflection on the impossible of poetry after Auschwitz and the response of Paul Célan... And you use the expression Images in Spite of All, which is the title of a book by Georges Didi-Huberman, but I only partially recognize myself in his analyzes.

All I can say quickly is: It would be pointless to look at the pictures for proof. On the other hand, they have the power of attestation, which is not the same thing. For me there is no moral prohibition on making films or watching images on any subject, including the Shoah and the camps. The whole question is how.

There are questions of dignity: for example if we could identify the naked women heading towards the gas chamber that we see in on of the Alberto Errera's photographs, this image would be unobservable: how could we look at women taken without their knowledge, in such a context and devastated? But since the image is blurry, and no one can be recognized, then we can look at it like a trace of what was.

There are questions of accuracy: for example cinema is an art of time, it can make time perceptible. When certain films for dramaturgical reasons contract time, they give a false perception of what was, a perception driven by the intention to produce pathos and fear in the spectator, but not to render a fair perception of events: it is which I think Saul's son does in many scenes in my opinion. There are questions of space, etc.

For me, any image and any film on these subjects must be an interrogation as if it has a hole in it, that's what Celan's poetry does, which guides me, for example when he talks about "half image - half veil" in Dialogue in the mountains. I am convinced that any image on the Shoah is at the same time a perception and a veil: each work must be aware of it and in a certain way show it, tell it.

zeitgeschichte|online: The French original title and the international English title are divergent. Do you think the two titles will influence some differences in the national and international reception of your documentary?

Cognet: I really don’t know. I do not speak English well enough to understand all the connotations associated with the words and phrase in the title. Simply, the people from the international sales of the film told me that it was difficult to translate into English, especially the aspect of "movement" within the French title "À pas aveugles”. They offered me several titles to replace it and together we chose this one: From where they stood, which indeed emphasizes another dimension of the film. But the two agree on the fact that these photographs are as much acts as images, if not more, on their bodily, physical dimension.

zeitgeschichte|online: How did the Covid-19 pandemic influence the film making?

Cognet: Not really, the shooting was in July and October 2019. Only sound editing and mixing have been delayed. Covid-related difficulties are now coming for the film's release. And I am writing to you having tested positive…

zeitgeschichte|online: Last but not least. What will be your next project?

Cognet: After all this journey I became convinced that I had gone as far as I could with documentary cinema. It is thus at a tipping point: only fiction now seems to me capable of prolonging it. I have two film projects to extend it, one of which is an adaptation of a novel by Aharon Appelfeld, the other a anticipation film which meditates on "black tourism". But I am only at the beginning.

Berlinale Screening of À pas aveugles on Monday, June 14th 21:30 at Open Air Kino HKW

The written interview with Christophe Cognet was edited by Rebecca Wegmann.

Zitation

Rebecca Wegmann, An impossible encounter with the past. Interview with French director Christophe Cognet about the need to represent the camps from the inside, in: zeitgeschichte|online, , URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/interview/impossible-encounter-past